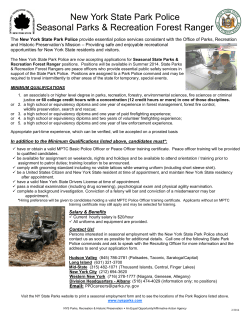

Document 164311