Bib-54301

25 -April 1975

ITED NATIONS

CONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL

COMMISSION FOR AFRICA

oan Regional Conference

]|n Hunan

H

C^jlro, 21-26 Jffcne 1975

UTILIZJfflON OP RESOURCES

SANITATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES

IN SELECTED AFRICAN CITIES

CONOTTS

Introduction --------------

1

Effects of housing on health ----------

3

Water supplies

3

-------------

Sewerage t drainage and solid waste disposal

------

5

Transportn-and^otheri strives

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

5

StUEnary" and conclusion

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

13

References

—

—

------""""

4

1575-886

---

E/C»«l4/HDS/7

SANITATION AHD <3*VIRONiraTAL SERVICES

IN SELECTED AFRICAN CITIES

Introduction

The environmental problems facing many African cities today, emanate from

their historical background and geographical setting and the failure of

national Governments and city authorities to adopt developmental priorities

I with respect to these,, Historical background is iiaportant because some cities

I founded during the colonial era are in the position of having well planned

I areas with modern facilities catering for the well-to-do minority groups side

I by side with unplanned areas intended for the African population and ill-provided

{ viitfe even the most rudimentary facilities. At the same tiiae3 most African

} cities .were created as centres of commerce and industry and relied on the

| surrounding rural areas to provide them with labour and supplies , the result

j being the twentieth-century phenomenon popularly termed "the rural exodus%

i Geographical netting is important because in the case of many cities, it was

; dictated by the wishes of and priorities set by the colonial Powers, who never

took account of proximity to basic supplies, such as water resources, which

would be needed by growing urban population*

In many cases developmental

priorities adopted by national Governments hardly existed until v&ty recently,

9. and those that did exist concentrated on the "per capita income" concept,

which has little relevance to Africa, where the rich are getting richer and

the poor are getting poorer and are left with no option but to stream to the.

cities from the depressed rural areas to try to eke out a living in the even

more depressed peri-urban slums*

Tho resulting urban environmental problems have been aggravated by the

. rapid increase in the population of African countries, particularly in urban

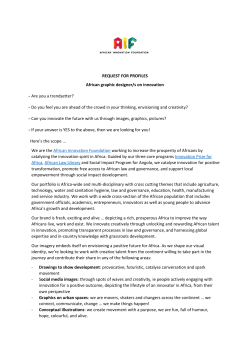

1 areas where it dLs estimated to be doubling every 10 to 15 years* i/ Figures

; show, that the urban population of Africa, which was 58 million In 1962, will

i reach 294 million, by the year 2000* 2/ Figures 1^-5 illustrate the phenomenal

; growth of several African csities*

j

:

!

i

j

\

These continent-wade increases in urban population are basically due to

vast migrations of people from the countryside, causing aome of the larger

cities to grow by as much as 8 per cent or more per year and to become ringed

by shanty towns in which shacks made from automobile tyres and packing cases

give miserable cover to migrants and create risk3 of social diseconomies far

greater than known so far, 3/

To city planners, with only limited resources, this influx has proved

a nightmare because they have been unable to provide adequate physical

\ facilities in respect of housing, supplies and services dealing with food,

[water, energy, roads, drains and sewage©

In no city is the housing prog^wte

[keeping pace with the increasing population, and the proliferation of peri-

j urban alums continues unabated0 There is a real danger that urban populations

■ in Africa will increasingly outdistance any urban services and housing that

! may be provided for then. hJ The housing problem is a bottomless pity and

i individual projects are too marginal to have any real impact,. The costs of

\ raajor programmes are so high they are ijapossible to affords and even so-called

' "low-eost housing" schemes tend to provide shelter for the medium rich rather

' than for the nore needy poor»

H

Page

The high growth rats o£ national urban populations resulting fron the

inflow of poor rural migrants leads to increasing unenploynent^ or imbalance

In incorao distribution and a general deterioration in urban living conditions*

Besides being faced with the problen of insufficient and inadequate housing

already referred to, nost cities do not have sanitary facilities of the type

and <the adequacy required,,

VJater supply and oewag© disposal projects often

appear to be fighting c losing battle, with backlogs growing faster than they

can be filled*

Roads, street lighting, etco, fall well behind the standard

required for decent living*. Health services, clinics, hospitals and maternity

and child welfare services are often in short supply*, SoIsdoIs, libraries*

coranunity centres and sports and recreational facilities fail to satisfy the

increasing demntU §/ Traffic congestion affects the transportation of goods

and persons

3n the face of such icnesoe odd3, the city atvfchoritieo beeone helpless

and- despondent in their efforts to aneliorate urban conditions due to a

shortage of both huoan and financial resources,, 3h the neantiae, the ijapov—

erished squatters remain underfed$ conaetraently their healthy energy and

morale becone considerably weakened and their working capacity greatly reducad.

This leads to low personal productivity» and they are retained in a state

of poverty in which they are unable to provide thenaelvea with even the

barest necessities «> 2/

To add insult to injury^ the problen of land speculation in African

cities and of the highly inflationary spiral of urban land pirlces creates an

obstacle to furfeher urban progress at a tine when population pressure continues

to build while city adninistrations, which are highly fragnental are woefully

lacking in capacity to deal with fche probleo«

fforeover, the extent to which

soek3 authorities can regulate land values is United oinco "private land

ownership" is protected by law and the uncontrolled profit aofcive is still

regarded as the stinulus for all progresoo

In the absence of any urbanization programs in many cities^ speculators

buy and subdivide laiai on which thay provide partially constructed roads

but no water supply, drainage for surface run-off, sewage facilities or

transport to take people fron the outi3kirf-s to the buiH^-iap sections of the"

cityo Land parcel© or lots of those estates are usually priced at fully

developed urhrui lar-d ^^a.iueRj xThich ai*e far beyond the financial capacity of

more than 90 per cont of the rural &*-nigrants of the city, who are left with

no alternative bt-t to put up structures of any kind to shelter then in areas

they occupy ir illegally*1 o The initial reaction of the city authorities is

to tear dorm these s'troctures, which arc considerod to bo urban blights j

however, the- only sprout up again a:-: fast aa they are pulled down* Hhr&yr&Pf

while occupants of Iii^>-^rade areas can afford to subscribe to the cost of

facilities such ao paved roadss drains3 transport^ power and water supplies

and refuse collection and disposal, including street cleaning^ services,

occupants of 3^w^rade areas cannot nake any financial contribution to the

amortization of tbo nunicipal loans necessary for tho extension of public

services^ Fron the available evidence, it appears that housing is the cost

serious envi-rtannental problen facing African cities and the roofcai^&as© of

the nany oooial problems encounterodo

POPULATION

SOME

GROWTH

MAJOR AFRICAN

Greater

2,000,000 i

1

Lagos

1

1

with

1

FIG

CITIES

1

Lagos City

1

1

1

Kinshasa

1/

i

1,000,000

1

W

t

I

:::?:■:*:■:

t

m

28::'?:

i

YnJYj

.j.iTW;

1UQ

Greater

1910

Lagos

1930

1950

Lagos

1970

City

1B90

1910

Kinshasa

1950

=

250,000

1901

=

41,000

1908

=

4,700

1967

=

1.500.000

1969

=

842,000

1970

*

1,200,000

iJYfiYi

1930

1950

1970

POPULATION

SOME

GROWTH

MAJOR AFRICAN

FIG. 2

CITIES

Ibadan

Accra

2,000,000

1,000,000

4

500.000

-

400,000

■:::::::::::-

300,000

/

200.000

w&

ilili-i

10 0,000

'.;W#i':«

50,000

•;■'.■;•!■■.■!''

4 0.000

■:::-y.y

30.000

<*•

20,000

10,000

■:'

ills??!

o

-

5,000

V

vXW

4,000

4.000

3,000

V.-

=,

2,000

a.

■

o

a.

1,000

1890

1910

1930

19S0

1970

1890

1910

1901

=

26,622

1690

=

200,000

1966

=

521.900

1967

*

720.000

1930

•Si;:;-;:

1950

1970

POPULATION

SOME

GROWTH

MAJOR AFRICAN

FIG. 3

CITIES

Abidjan

Dakar

2,000,000

1,000,000

500.000

400,000

300,000

200.000

"■.■.■■■.-

10 0,000

——

50,000

4 0,000

4

3 0,000

/

20,000

A

ltd

/

10,000

::::-::::x:

O

WOO

-

4,000

<

—i

3

2,000

:::::::::::::

0.

o

Q.

1,000

1130

1910

19.30

1950

1970

1890

1910

1904

=

18.400

19)0

=

1.000

1969

=

677,000

1966

r

400,000

1930

1950

1970

POPULATION

SOME

GROWTH

MAJOR AFRICAN

FIG.

CITIES

Nairobi

4

Mombasa

2.000,000

1.000,000

i

500,000

400,000

0

300,000

200,000

i

10 0,000

*e,ooo

40,000

M

4

/

J

30,000

20,000

4

10,000

A

■I"

4

:

:

:-;■:■:-;-;■

o

-

4,000

<

3,000

:'■:'■:■:':■:■:

1

:

I

o

a.

':

1.000

1190

1910

1Sl30

1950

1970

1890

1910

1906

=

11,500

1906

s

30,000

1970

=

507,373

1962

»

179600

1930

1950

1970

POPULATION

SOME

GROWTH

MAJOR AFRICAN

Addis

CITIES

FIG.

Ababa

Dar

es

5

Salaam

2,000.000

1.000,000

f

$00,000

400,000

3 00,000

200.000

10 0,000

A

50,000

4 0,000

d

A

3 0,000

20.000

10.000

o

-

4,000

^

3,000

3

2,000

■::-:::::':

:'-:?:'-: :': ':-

1

So-:-:

a.

o

a.

'■;':■;■■'■

■:;:o:::::

■:';■'■'■'■■■

1,000

10»0

1910

1&30

1950

1970

1890

1910

1908

=

35.000

1900

=

20.000

1967

=

637,800

1970

=

353.000

1930

1950

•y.-yy-

1970

E/CNoH/HUS/7

Page 3

Effects of houginj^on_healjji

The indices used to determine the effects of dwellings on the health of

a population include density, ioe«j the number of persons or houses per unit

area; the number of persons per roomj the existence of utilities3 such as

watert sewer, gas and electricity, and the physical condition of the dwelling

unit, Those factors play a major role in mortality and morbidity rates in

African cities 8 2/ Overcrowding, poverty, cultural or social deprivation^

malnutrition and inadequate social services of ten lead to a proliferation of

communicable diseases and endemic diseases© Moreover) ^he environment of the

homei especially where sanitation facilities are concerned plays a major role

in the occurrence of certain parasitic and helminthic infections. Furthermore!

overcrowding, poor ventilation -ind associated atmospheric pollution load to

an increase in the 5ncidence of respiratory infectionsc

Environmental services in several African cities will be examined in

detail in order to assess the;.r impact on the lives of African urbaniies«

VJater supplies

It is estimated that over 80 per cent of Africa's total population has to

get water from suspicious or badly contaminated sources and that 33 per cent

of all urban dwellers collect water in buckets froi3 standpipes and store it

at bome7 where it is likely to become contaminateda

Another 33 per cent

take watar wherever it is found, usually fron unsanitary wells and contaminated

streams,, The quality of most of this water is low| and most bacterial, viral

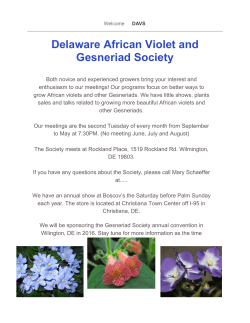

and parasitic diseases caused by contaminated water are prevalento Table 1

reveals the situation regarding water supplies to urban African populations

over a decade ago,

It shows that very few households were supplied with water

at that time; and a survey of a few African cities indicates that the per

capita supply situation lias deteriorated remarkably as a result of the rapid

Increase in the urban population,, £/

It is important to assess the situation with regard to water supplies in

a number of African cities since water plays an important part in. the transmission

of cholera, typhoid fever* bacillary and ano^bic dysentery, poliomelitis and

infectious hepatitia in Africa0 rihser is also implicated indirectly in the

transmission of such diseases as malaria^ yellow fever- filariasis and onchocerciasiatt

Come parasitic diseases r:voh as schisvosemiasis and dracontiasis

(Guinea worn) din which irhe causative organism undergoes changes inside small

aquatic animals before being liberated need the agency of water to complete

their life cycle of transmission* 9/

■later supplies tc urban populations? whether obtained from underground

sources or from streams and lakes, ciust therefore be protected against pollution

by iiapounding vo reduce organic matter contentj screenxr-g to free the water

of larger objectG3 aeration to remove odours, sedimentation to renove suspended

particles, slow falteration to reduce turbidity3 bacterial counts: chemical

precipitation and by oth^r special treatment methods so as to ensure a supply

of potable and palatable water of satisfactory quality* Thin question will

be examined as it relates to a number of African cities in subsequent chapters*

Page 4

Urban water supply3 1962

Percentage of population served and ungeryed in African c

Urban population served

House

Public

connexions

Unseryed

outlets

.

. 25

35

40

Libyan Arab Republic

25

40

35

Morocco

30

25

45

Tunisia

50

35

15

80

10

!0

Angola

15

25

60

Cameroon

10

25

65

Central African Republic

10

20

70

Chad

10

15

25

15

40

45

15

40

45

15

20

65

Ghana

10

65

25

Guinea

15

35

50

Ivory Coast

15

25

6o

Kenya

25

50

25

Madagascar

15

45

40

Mali

1O

35

55

Mozambique

10

25

65 ;

5

25

70

Nigeria

10

35

55

Senegal

20

30

50

Sierra Leone

15

25

60

Somalia

10

30

60

Sudan

30

60

10

United Republic of Tanzania

15

' 45

40

Congo

20

35

Uganda

20

40

40

Upper Volta

10

25

65

Algeria

.

Egypt

Ethiopia

Gambia,

Rhodesia, Malawi

.

Niger

Source*

B.H9 Dietrich and J«M Hendersen,

.-

•

'

75

Urban water supper conditions and

needs in seventy-five developing countries (tJHO» Public Health paper

Geneva, 1963*

3/ai/l4/H0C/7

Page 5-

-%

Sewerage, drainage and solid waste disposal

To assure a health urban population anywhere, storm water and,sewage

effluents should be discharged into water courses only after proper treatment.

Solid wastes nust be disposed of to prevent their acting as breeding grounds

for disease carriers. Stom water nay be directed through drains and sewers,

and sewage should be treated either in settling tanks or by alternative

methods suitable for the geographical location of the city concerned. In many

African cities, sewage is disposed of either in septic tanks or in cesspools,

by pair or pit latrines. Solid wastes are normally collected fron depots,

by backdoor picfo*ip or by doorwto-4oor pick-up and disposed of by sanitary landfill,

incineration or composting.

In parts of sone African cities, even rudimentary

facilities for the disposal of solid wastes are lacking so that open spaces

are littered with deposits. Watercourses passing through and cities act as

sewers and cesspools whose smell alone constitutes an environmental nuisance

and whose disease-carrying capacity poses a serious health hazard to all persons

living in their Vicinity.

Transport and other services

Transportation in many: African cities has been affected by the general .

problem of population increase and the resulting inability of city authorities

to provide adequate means of moving people and goods from one part of the

city to another. As their incomes have grown, nenbers of the welMto-do

miaority have acquired private vehicles in increasing quantities, which has

led to traffic congestion and air pollution and the frustrations that accompany

then. Foreign exchange difficulties have prompted many governments to'halt

the importation of new vehicles, and as a result several cities abound in

dilapidated automobiles which create intolerable environmental hazards*

Poor urbanites depend on public transportj and with the increase in

urban population, the available means have been: so overstretched that people

are always packed in uncomfortably from their miserable dwellings to their

places-of work. The peri-*irban slums are constantly expanding as the in-migrant

population increases, and the available transportation means fail to cope,

thereby aggravating the situation.

TJhere energy supplies in Africa's urban centres are concerned, residents

of well-to-do areas get and can afford to pay for supplies of electricity

and/or gas for lighting, heating and cooking. The poorer segments of the

urban, population depend on wood and charcoal for all their cooking and heating

needs as they are the only resources they can afford. The pollution and nuisances

this causes in poor urban households oust be: axperienced to be believed^

Health services and educational and recreational opportunities appear

to be as inadequate in most African cities as the other environmental facilities

mentioned above.

Eight African cities, (Casablanca, Cairo, Lagos, Abidjan, Addis Ababa,

Nairobi, Lusaka and Kinshasa) have been selected as subjects for the following

case studies intended to highlight some of the urban environtaental problems

already discussed in the preceding paragraphs. An analysis of environmental

services in such fields as housing, water supply, sewerage, solid waste disposal,

B/CHa4/HDS/7

Page 6

transportation, energy supplies, health services and recreation reveals a

.pattern which is repeated in city after city with only Elinor differences*

Casablanca

Casablanca is a typical example of a city comprising a number,of separate

different cities, each with its own distinctive environmental setting and

problems. On the one hand, there are modern districts which were built for

French citizens during colonial tiiaes and are now inhabited by upper-class

Moroccans. These districts were well planned and are provided with an iwple

supply of high quality water; excellent sewerage systems; brightly lit and

well swept streets, Where garbage is collected daily and bus transport functions

well and well-kept, green parks exist for recreation^ lg/

On the other hand, there are the old Moslem quarters, surrounded by walls.

There inner cities are crowded and airless, with little sunlight to relieve

the damp and gloom. New medinas have sprouted up around the old.ones, and they

too are in a sorry state of environmental squalor. ' 'Their vast unbroken

communities* which are overcrowded and wallowing in poverty and dirt, stretch

along narrow, airless streets without adequate water and sewerage systems.

Their population is plagued with serious health problems.

The thied and most complex type of city within Casablanca is the shanty

towns. These are called "bidonvilles" or cities of oil drums. They are vast

conounities whose buildings are constructed from flattened oil drums, wood

scraps, etc. Fopolation densities of the bidonvilles. are extremely high and

are reported to be increasing. The bidonvilles of Casablanca have over

:

180,000 ±J/ residents, and their population is growing at a rate of 7 per cent

per year, Moroccan Government authorities view the bidonvilles as a threat

to security, a blot on the national character and an unmitigated evil and have

had them fenced in* There is a strict prohibition against their further

expansion and the alteration of the existing shacks. Often such structures,

which the authorities regard as a shame and scourage that must be eliminated

for the sake of national pride, are demolished only to appear again overnight

at a nearby site.

6' bidonvillea ^re overcrowded, with narrow, often unpaved streets where

garbage and waste are strewn about.; Housing consists of miserable shacksj and

their occupants get water from fountains, which are few and far, between.

The inadequate and insufficient housing in Casablanca and the serious

unemployment problems faced by ito citizens are recognized as being two facets

of the problem of poverty arid that both of them are tied to the problem of

rural migration to the cities. iJhereas the central business districts and

high-class residential areas are beautiful and have top quality services, th©

remaining areas are poor, dirty, unplanned and lack almost all public services.

The inhabitants are without resources .with which to improve these districts

thenselves .and have no political power to attract Government interest and

assistance.

*

E/QU14/H0S/7

Page 7

■Hie urban popuia-tisii cf Morocco as a whole ia growing at. a rata of

6,5 per cent a year, and it is estimated that it will reach 10 million by

19§5«

The rate of expansion of urban areas and population far outstrips

the capacity of the Government to raise or even maintain, the level of services

in fields ranging from water supply and sewerage to'hous:tagf welfare and even

education,, Older areas of the city are deserted by the wealthy and decay.

while suburban areas spread outwards with virtually no iorethoucht or

planning by the Governmehto

TJhat measures* then? have been taken or are envisaged to tackle the

eexdous environmental problems of Casablanca? Despite problecs due to the

fact land values have been grossly distorted by speculatorss the Government

embarked upon a number of far-reaching shcene3 in the postwar period. In.

1952, a latf was promulgated which provided a strong and effective instrument

for city planning and gave the Government power to develep where and Nhen it

chose* with co-operation fron private sector,,

A new plan aimed at combatinc *£he .development bidprrsrilles and overcrowding

in the; medinas his been adopted0 It focuses on housing policy and on large

developments on State-owned land$ where private individuals - from the

bidonvilleSj it is hoped - might construct their own houses .assisted by

Governoent-guaranteed loans on easy terasa In addition? the Government puts

up teoporary houses t as a half--way measure between the shacks of the bidonyilles

and the type of dwelling mentioned aboveo

The Government hast: in addition, insiituted "sito-Gm-oervice" schectes

whereby it assists large low-income housing devolopniesit by preparing a layout

fop the area to be developed3, installing basic aerviceej'syr-b as i-oadaj, waterf

sowerago and elebtricityf and then selling the lots at p.^.^33 below theii*

market valuo0

i ,

!«■

I'

j1

i:

i;

The ownorst of these lo-to sha3.1 conaiTticfc their own houses on

them with assistance provided by a low-aaost hoiising loan pro-granno*

Self"help housing construction has also becor

in efforts to eliminate

an important objective

These are gallant efforts designed to tackle soi'ious, prcbleao# which .

States td.th vast resources would find wolX-nlgh iapossibXa to eliainate©

Cairo

The urban population of Sgypt, which repi^3semted 31 per cent of the total

population of the country in 1947? had ricor. to t\2 per cer-t in 1970a 3igbty

per cent of the total urban population was crowded into Cairop which had

a density of 20^000 people per square kllbnetre*- }2j The city has a settled

population of about 5 million people and mobile population of about 1 nillion,

This has created very serious urban problems especially whore the pro?"iai£>ri

of housingo i3/

Page 8

Room capacity in Cairo has not increased at the.same rate as the population,

so that now an average of 5 people occupy a single room. This overcrowding,

which Is especially severe in the poorer parts of the city, has led to serious

problems of refuse disposal and to pollution of the waters of the Nile. Sewage

systems have become overloaded, and 75 per cent of the effluents consists

of either only partly treated water or of untreated water, which just gets

thrown into open drains* Garbage is collected from the streets manually and

dumped outside the city. The populated suburbs are now encroaching on these

public durap3, which have large fly populations and other disease vectors.

Transport problems are serious in Cairo as there are thousands of automobiles

emiting smoke which pollutes the air, and driving conditions are generally

hazardous. Tfater supplies in Cairo are good by comparison with those of other

cities, as shown by the figures given for Egypt in the table above.

Lagos suffers fron serious congestion, environmental inadequacy and

disorder, made aore complicated by administrative and political complexity and

confusion of responsibility for corrective action. Greater Lagos has in fact

been described as being on its way to becoming the Calcutta of Africa. i&/ Its

population more than doubled between 1952 and 1962 and had reached 1»5 million

by 1967.

These increases exacerbated the problems of an already rapidly

deteriorating urban environment in Lagos and posed nearly insoluble management

•difficulties in a situation where resources were scarce.

The city can be divided into a number of districts with different

environmental settings and problems. The high-grade residential districts have

wellr-planned layouts, and most of the houses in them are occupied by important

members of the community ouch as civil servants and top people in commerce

and industry. i§/

The medium-grade residential districts are also well planned and possess

good household amenities. The structures in then are modest, small-sized

bungalows, of which there are between 12 and 16 per acre. The lower-raediuiagrade residential districts started out as slum areas but were later improved.

They constitute casia of planned layout in a wilderness of confused housing. }

They have wide streets, but the traffic flow is hindred by crowds of petty

traders whose movable "counters" live then on both sides*

They were developed

by speculators who constructed multi-storied houses with numerous rooms for

hire to immigrants. Many of these houses have no lighting and/or adequate

toilet facilities.

The low-grade residential districts have never been planned.

The houses

are very poor and are separated by narrow, confused lanes*

They are

indescribably squalid, and access to them is by narrow footpaths, which also

aerv& as drains for household watero

Household equipment and facilities

are most inadequate and unsatisfactory and the generally unsanitary conditions

have led to serious cholera outbreaks.

Other areas of Lagos have cheap,

/

Page 9

-H-s on to

Swellings*

bore

factories hare been

s*

poor by unscn^ulous entrepreneurs.

aerp are ^ a ff -11

hirfier olaaa residential area,

p

Wl. Itat hc^etolds, howerer,

flyBt«

or

^^

disposal of night

*,,

i

seroral points into oobile tanks.

tipp^ Sep* where their ^

Between ?«4 9 P.o.each

and

regiona plai>nix»e

collection

for the

then pulled by tractors to a

city where sepSto

£ known action at

lopnent B^ard, which has

%*•**

Page 10

The Board began by demolishing sooe of the worst slams in a United

area of Lagos Island and replacing the% u*eff©otdhrely, with ships and otti&s

buildings, 'it had no power to draw up statutory town plans until the military

passed a decree in 19^7 enabling it to do so* The work of the Board is

seriously hampered by budgetary limitations and a shortage of staff*

Both the Federal Government and the state governments have failed to

acknowledge the gravity of the situation in and around Lagos, even though

the size of the metropolitan population is approaching the ,2 aiUta* nar^.

It is, liowver, encouraging to note that a master plan for retttilding Lagos

is currently being prepared with a. view to/Solving some of the serious

environmental problems facing.tho city, ££/

. ■

Addis Abqba

'•■.-■■'_.-...*

'."

■■

The capital city of Ethiopia « has an estimated population of about t

900,000 which is growing at an annual rate of 9 per cent, 22/

'

■ ■

'

There *s an acute housing shortage in Addis Ababa, and overcrowding has

assumed serious proportions. The bulk of the population lives in su^™™^

seiiHperiaanent dweUings* which are in bad repair,-have inadequate lifting and

ventilation, no piped water,.minimum toilet and bathing facilities,,and are.

located Inr. areas* with no access to safe sewage disposal facilities.

In addition, not enough .dwellings are bfeing constructed to satisfy the _

current requirement of 82,000 units for the lower income groups in Addis Ababa

and to replace exiting sub-standard 'dwellings* and it appears that, overe rowding

will be a feature of Addis Ababa for a long tiiae to come,

:

It i« estimated that.6l,3 per cent of the houses in Addis Ababa have no

access to proper toilet facilities" so that most open spaces and streams in

the city are used as open-air toilets, 2,U'per cent of the households have

flush toilets while 36.5 per cent use pit lsttrineso

Lfost urbanites get water from public standpipes serving hundreds of

users and only a few buildings Have piped water and electricity. Recreation

facilities* are inadequate, as are the few schools and health centres in

existence which are also poorly equipped.

The public transportation system

is composed of many old buses, which become intolerably crowded during rush

hours

The only major planned new development in Addis Ababa is the construction

of sewage lines for the first time in the city's history. Provision is being

nade for additional water supplies by laying new pipes and constructing

additional reservoirs to supplement supplies which have become intermittent

in certain parts of the city,

'

Nairobi

Tho city has a population of about 600,000 which is growing at an

annual rate of 6 per cent* it is estimated that it will reach 1 tdllion

by 1983, 23/

■■*

E/CN*l4/H0S/7

Page 11

Its residential areas provide a typical example of the segregated districts

initiated during the colonial era.

Those parts originally occupied by expatriates

but now inhabited by the well—to«do netnbers of the local community are well

laid out and provided with all the facilities one expects in a modern city*

The African quarters were built in such a way that they provided only the barest

necessities.,, and housing consisted of small single rooms for individual

occupancy with no lighting or water-borne sanitation*

In additions there are

peri««rban slun areasj which arc inhabited by rural in--migrants? who live in

temporary structures with no sanitation facilities whatever0

The housing shortage is generally considered to be the nost serious

problem facing Nairobi authorities*

Nairobi's requirements are stated to be

5#88O houses per apnun between 1970 and 1974«

I:foreoverP if the degree of over

crowding is assessed in relation to housing overspill population at an average

of 5»15 persons per household? at least 10,000 dwellings would be required each

year*

In considering these figures f it should be noted that the current

annual rate of construction is only 2^000 unitsQ

Programmes initiated by the

National Houatag Corporation will be unable to meet the current demand even by

1980«

Meanwhile overcrowding had become so serious that one snail room is

occupied by three or more personss and 70 per cent of Nairobi8s dwellers live

in the' peri^arban slums in low-cost* sub-otandard housing with no water supplyf

sanitationj or sewage collection and treatment facilities0

The authorities

report that the provision of adequate sanitation facilities has become a

critical problem,.

As the population grows, water supply systems often break

downj and it is recognized that water supplies in Nairobi must be greatly

expanded before 198Oa 25/

Government authorities have adopted several schemes in an attempt to solve

Nairobigs environnental headaches0

To relieve the present congestion^ they

have repeatedly urged people to go back to the land; but since land is scarce,

and urbanites cannot afford to buy the land which remains at its inflated

value-- this policy has not been successfulo

ttithin Nairobi- city authorities

have frequently resorted to arbitrary demolition of peri-urban slums without

providing alternative accommodation for their displaced inhabitants.

For

examples in 1970 alone, 4*000 dwellings were demolished in the city ostensibly

to stave off possible outbreaks of communicable diseases j however, they only

mushroomed elscstfrere overnight^

To conpI:L.a*e nattcro further; there is the problem of corruption in

housing allocations and purchases with the result that most houses are owned

by wealthy Nairobi residents who charge exorbitant rents which poor urbanites

can lll-efford to paya

I'lhere other environmental servicas are concerned; Nairobi appears to be

one of the most fortunate cities in black Africa©

'

The City Council runs

efficient services for cleaning streets and disposing of garbage and public

transport appears to bo adequate evan though the increase in the urban population

has created a serious problem of congestion in this area*

Moreover, the number

of private vehicles in Nairobi has increased to such an extent that traffic

congestion is now worrying city plannerso

V

Page 12

Educational and roci^aidLonal ^acxliiioe- appear- excellent although they

are also adversely affected by the rural exodus* TJnenployneat and under-'

ecployoent have reached unmaEagable proportions, and governmental authorities

appear to have no solution t6 them*

Kinshasa

9

f

Efciring the period 1959 and 1964? the total urban population of Zaire

was Increase rig nuch faster than the population as a wh. ler. with Kinshasap

the capital, growing at an annual rate of 10 per cento

In the 5 years between

1959 and 1964? it grew from 400,000 to 800j000e 2§/ The latest figures show

that this city, which was originally planned for 400f000 inhabitants^ is

now growing at the rate of 11 per cent per annum and has reached the lp300j;000

mark, £7/

"Hi© situation ia similar to that in Casablanca and Nairobi in that the

Belgian colonial authorities constructed cities Tiithin a city,,

2h Kinshasa

there are areas comprising well—constructed buildings with excellent sanitary

facilities surrounded by depressed areasr originally designed for the African

population^ which have no adequate sanitary facilities©

Inoigranto to

Kinshasa have squatted in the peripheral areas whenever they could find free

open spaces©

In such settlements, access to good quality water supplies*

and facilities to dispose of waste does not existj and hygienic conditions are

deplorable^

In the central part of the cityt transportation problems have

become unsolvable ar.d congestion has reached nightmarish proportiono«

Lusaka

In Zambia there ie a I^igh rate of population movenent fixan the rural

areas to the towns.

Between 15)65 and 1970 the country?s overa>J. urban

populations increased by about 46 p«3rcent owing to an iaf low into the towns

of as many slb 6f000 squatter families per year. These migrants settled in

the outskirts of cities like Lusaka,? where they put up temporary nud huts in

places where no roadj water8 sewerage or garbage collecting facilities are

providedo

Unen^loyed pori-*irban dwellers novo 10 to 15 milea out of town

to eke out a precarious existence by cutting trees and buxirkng charcoal for

sale in, the cityft

The areas cleared by then are then cultivated with no

recourse good hesbandry*

It ic feared that this practice night eventually

turn the Xar/ around Lusaka into a

The. water ewpply in Lusaka Is drawn fron underground aquifero fffliit

for ttio central areas of the cityi but as the population of the perirurban slunuj t«argeons# these supplies are becoiuing overstretched7 and the

future will beblasJcif iraaginative progrannes are not embarked upon*

In order to 3xprove fsnaitary conditions in the suburbs tho Governiaent of

Zambia has launched "site-and service" schemes^ where roads and water and

E-ewersgo facilltioB aro laid cut before migrantc are given assistance in

kind to construct tlieir own dwellings on a self-4ielp basis*

Schemes such

as this take care of only a very small part of the demand since the exodus

fron tho rural areas to Lusaka ia continuing unabated*

If

1- ■;

1J

( .

Pago 13

There is a ndod to construct an est&aated 7,000 new dwellings per year

if

■f

1*

city of Abidjan^ g§/ Only about 5,000 were constructed in 1971 and

iiboming migrants experienced serious housing difficulties. Abidjan received

avast Influx of ruraltiigrantsy many of whoa are very poor. They construct

efcoap, unhygienic duellings on the city periphery, where they live in

ojxtreocly severe environmental conditionso

The city faces serious problems with respect to disposal of waste*

idustrial effluents and all sewage from the city are fed into tho la©3ons

$3und Abidjan, which seriously pollutes then, produce offensive odours and

rffact ?iarin© life.». > .Nevertheless, there is as yet no legislation to stop

discharge,'of untreated wastes and sewage into the lagoons.

;:

Affluent parts of Abidjan have f-irst class houses on well lit and carefully

Iteid ottt streets* These parts of town are provided with adequate and efficient

iwlronncntal servicesf however, even these services arc threatened by the

of rural migrants into the city*

SUttMRY AND CONCLUSION

aivironnental problens encountered in Africa's urban centres are a direct

t of the rapid rise in urban population due tb massive human noveaaents \ . the depressed rural areas. Sone of tho larger cities grow by 8 per cent

lousing,

per year. As a result, there is a serious bacJcLo^ in the provision of

Gince their housing deaands are unsatisfied, imnigrants construct

iirt-«rban shanty towns in which shacks made from gasoline tins, old automobile

||rre3 and packing cases provide a miserable cover and create risks of greatippcial diseconomies.

;

Ouch areas have inadequate water, lighting and sewage 3ysteosf and are

% serious hazard to health. The truth is that city authorities do not have the

iteeources to attend to the sanitation and other environmental needs of the

masses r

■

"Gite-raid service" 6cheneo," self-rhelp efforts and other prbgraOMS designed

to aneUorate these conditionn tend to be hampered by existing land tenure

Hastens and speculation by private landowners, which make,the coot of urban

I

too high for poor city dweller3 to afford.

;

A possible solution to these urban problems lies in a combination of

Jtigorous programmes to improve life in tho rural.areas and imaginative

bchenes to create a new urban situation in Africa, suited to the continent's

own values and not blindly based on tho patterns already laid down ^T^e

:»estern world. Building codes and regulations must, for example be revised

i%ake into account the realities prevailing in African countries*"

Page 14

REFERENCES

1.

T.G, McGee; The UiH^anization ftcocess in the Third 'forJLd (London, G. Bell

2.

M. Jupenlatz, Cities, in Transformation! Tho yrbangouatter Problen of the

and Sons, 1971)«

.. "■/.

.

"

'".'.-

.

-\ ■*„.'■'

Doveloping Ttorld (University Queensland Pres3, 1970;.

3.

Barbara ;7ard and Rene Dttois, Only One 5arth (New York, N.J. Norton and

Company, 1972).

4.

Ilorld Bank, "Urbanization" (a sector working paper) (Tfashington, D,C. 1972).

5.

ft.H. Chinn, "Social problems of rapid urbanization with particular reference to

6.

Jupenlatz, op.cit.

7.

3H0, Use of'^idepiqlofw in Housing! E^flrammea and in PlanninK Human

8.

UNICEF, Childrena YouUij Jfooen and peyelopment Plans, Homo Conference (1972i,

9«

M# Roy, "Problems of water supply, sewage and waste disposal in Africa",

First All-African Seminar on the Hunan Environment, Addis Ababa, 1971«

British Africa", in Urbanization in African Social Change (1973) pp.9-0.0li

.■

.

Settlements (Geneva', 19/4).

10# M»K» Johnson, Urbanization in Eforocco (international Urbanisation Survey)

(The Ford. Foun3ation, 1973). '

,:

11. Janet Abu-Lugjiod, "Cities blend the past to face the future", Africa Report,(1971) Vol.16, No» 6, pp. 1>15.

12. Arab Republic of Egypt, National Report to the United Hationg Conference on

the Hunan Itait

13. N.C. Otieno and C» Pineau "The Hunan 2nvironment in Egypt" (1971).

14. Co Roser* Ifrbanization in Tropical Africa A Deaoflraphic Introduction,

International Urbanization Survey (The Ford Foundation. £973)•

15. A.L. J.5abogunje, Urbanization in Migeria (London University Press1,

l6« A,Lo Mabogunje, op. cit.

. ..... :.

17. L, Green, and V. Milone, Urbanization in Nigeria , an International Survey

Report (Ford Foundation, 1973).

.

,

.

18. Federal Republic of Nigeria, National; Report to the United Nations Cohference

on the Human Qwrironoent (1972).

19. G. Pineau, and N.C. Otieno, The Human aivironment in Nifjeriat (April, 1971) •

J5/CBWA/H0S/7

Page 15

Green and

S.A. Thomas, "Master Plan being prepared to rebuild Lagos", Ethiopian

Herald, Vol. XXIX, Mo.686, 1973.

22. Roser.

23. Ibid.

24. Republic of Kenya» National Report to the United Nations Conference on

the Hunan Bmrironoent (1972 jL

25. L. Laurenti and J. Gerhart, Urbanization in Kenya (international Urbanization

Survey) (Ford Foundation, 1973)t

26. Henri Khoop, "The Sex ratio of African squatter settlement.

hypothesis building", African Urban Notes, No. 6,1971.

An exercise in

27. C. Pinoau and H.C. Otleno, The Hutan Enviromaent in Zaire (March 1971).

28. C. Pinoau and H#C. Otleno, The Hunan ISnyironpent in Ivory Coast (April 1971).

© Copyright 2026