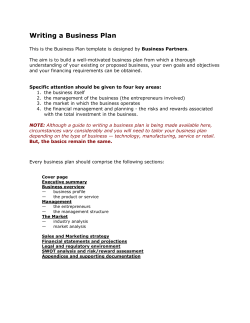

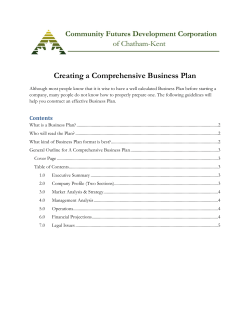

4 Conducting a Feasibility Analysis and Crafting a Winning