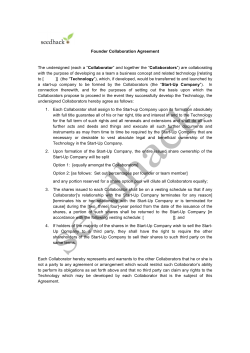

H URDLE T B