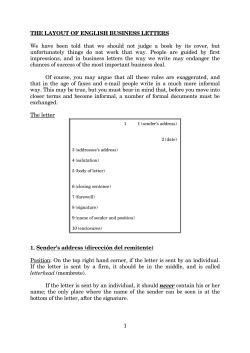

An Introduction to Ecotourism Planning Volume l