Minireview Acupuncture for Chronic Nonbacterial Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A

Journal of Andrology, Vol. 33, No. 1, January/February 2012

Copyright E American Society of Andrology

Acupuncture for Chronic

Nonbacterial Prostatitis/Chronic

Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A

Systematic Review

Minireview

PAUL POSADZKI,* JUNHUA ZHANG,{ MYEONG SOO LEE,*{ AND EDZARD ERNST*

From the *Department of Complementary Medicine, Peninsula Medical School, Universities of Exeter and Plymouth,

Exeter, United Kingdom; the Evidence-based Medicine Center, Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine,

Tianjin, PR China; and the `Brain Disease Research Center, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Daejeon, South Korea.

ABSTRACT: The objective of this systematic review was to

assess the effectiveness of acupuncture as a treatment option for

chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Eight databases

were searched from their inception to October 2010. Randomized

clinical trials (RCT) were considered if they tested acupuncture

against any control intervention or no therapy in humans with

chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. The selection of

studies, data extraction, and validation were performed independently by 2 reviewers. The methodologic quality of all included

RCTs was assessed using the Jadad scale. Studies of

stimulation of acupoints other than by needles were excluded.

Nine RCTs met the inclusion criteria. They all suggested that

acupuncture is effective as a range of control interventions. Their

methodologic quality was variable; most were associated with

major flaws. Only one RCT had a Jadad score of more than 3.

The evidence that acupuncture is effective for chronic prostatitis/

chronic pelvic pain syndrome is encouraging but, because of

several caveats, not conclusive. Therefore, more rigorous studies

seem warranted.

Key words: Chronic abacterial prostatitis, effectiveness, complementary and alternative medicine.

J Androl 2012;33:15–21

C

affected with CP/CPPSs; however, the therapeutic

effects of acupuncture for this condition remain

uncertain (Capodice et al, 2005). Some studies suggested

neuropathic mechanism of action involved in CP/CPPS

(Chen and Nickel, 2003), but this is not supported by

sound evidence.

Wang and Han (2008) published a systematic review

and meta-analysis of acupuncture for CP. However, this

publication is burdened with a high risk of bias due to

ambiguous inclusion criteria and lack of appropriately

defined interventions, comprehensive search strategy, or

quality appraisal. Significant heterogeneity of the trials

included in meta-analysis was neither explained nor

accounted for. Specifically, Wang and Han (2008) only

included 3 of the 9 randomized clinical trials (RCT) we

managed to locate. Moreover, the authors failed to

critically evaluate the primary studies that they reviewed.

Also, they included such disparate interventions as

moxibustion (in 7 of 13 studies) or pricking needling

and bloodletting (in one study). Therefore, a more

rigorous systematic review is required in order to

determine the best evidence on acupuncture for CP/CPPS.

The aim of this systematic review is to summarize and

critically evaluate the RCTs testing the effectiveness of

acupuncture in treatment of CP/CPPS.

hronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome

(CP/CPPS) is a clinical entity defined as urologic

pain or discomfort in the pelvic region, associated with

urinary symptoms and/or sexual dysfunction and lasting

for at least 3 of the previous 6 months (Anothaisintawee

et al, 2011). The syndrome can affect 10%–15% of the

male population and results in nearly 2 million

outpatient visits each year (Murphy et al, 2009). Collins

et al (2000) concluded that CP/CPPS is difficult to

diagnose, and the routine use of antibiotics and alphablockers to treat chronic abacterial prostatitis is not

supported by sound evidence.

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese method of

medical treatment involving the insertion of fine,

single-use, sterile needles in acupoints according to a

system of channels and meridians that was developed by

early practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine more

than 2000 years ago (Capodice et al, 2005). Acupuncture

is a ‘‘natural’’ therapy, attractive to many patients

Correspondence to: Paul Posadzki, Complementary Medicine,

Peninsula Medical School, Universities of Exeter and Plymouth,

Veysey Building, Salmon Pool Line, Exeter EX2 4SG, United

Kingdom (e-mail: [email protected]).

Received for publication February 1, 2011; accepted for publication

March 17, 2011.

DOI: 10.2164/jandrol.111.013235

15

16

Journal of Andrology

N

January February 2012

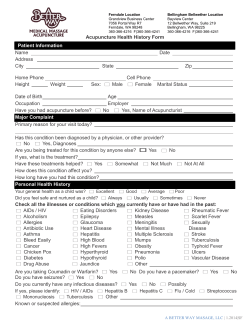

Table 1. Quality assessment of the included studies

Author (year)

Random Sequence

Generation

Appropriate

Randomization

Blinding of

Participants or

Personnel

Blinding of

Outcome

Assessors

He et al (2004)

He and Xu (2007)

Hu et al (2005)

Huang et al (2005)

Jin and Ji (2008)

Lee et al (2008)

Li and Wang (2006)

Wang (1997)

Zhang (2009)

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Materials and Methods

Literature searches were performed to identify RCTs of

acupuncture for CP/CPPS. The following databases

were used: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled

Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED,

PsycINFO, Chinese Journal Full-Text Database, and

Weipu Scientific Journal Database (from their respective inceptions to October 2010) using the following

search terms: acupuncture, prostatitis, chronic nonbacterial prostatitis, chronic abacterial prostatitis, chronic

pelvic pain syndrome, and prostatodynia to identify all

relevant RCTs on the subject. The reference lists of the

initially identified papers were scanned for further

relevant literature. No language barriers were imposed.

All retrieved data, including uncontrolled trials, case

studies, and preclinical and observational studies were

reviewed for safety information. However, only RCTs

testing acupuncture in adults with CP/CPPS were

included. Studies were excluded if they were uncontrolled (eg, Chen and Nickel, 2003; Honjo et al, 2004) or

used different a method of stimulation of acupoints (eg,

warm needling moxibustion; Yu and Kang, 2005;

Zhong-Xin, 2009) or electroacupuncture (Li, 2005; Lee

and Lee, 2009). Two independent reviewers validated

data using a predefined standardized form and assessed

the methodologic quality using the 5-point Jadad scale

(Jadad et al, 1996). Any differences were resolved by

discussion.

For the purpose of this review, CP/CPPS was defined

as urologic pain or discomfort in the pelvic region,

associated with urinary symptoms and/or sexual dysfunction and lasting for at least 3 of the previous

6 months (Anothaisintawee et al, 2011).

Results

The search strategy generated a total of 128 references,

of which 61 were considered to be potentially relevant.

We did not locate any unpublished trials. A total of 27

clinical trials were retrieved for further evaluation, of

which 9, involving 890 patients, were eligible for

inclusion (Wang, 1997; He et al, 2004; Hu et al, 2005;

Withdrawals and

Dropouts

Sum (Jadad Score)

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

2

2

1

1

1

4

1

1

2

Huang et al, 2005; Li and Wang, 2006; He and Xu, 2007;

Jin and Ji, 2008; Lee et al, 2008; Zhang, 2009). Eight

RCTs originated from China, (Wang, 1997; He et al,

2004; Hu et al, 2005; Huang et al, 2005; Li and Wang,

2006; He and Xu, 2007; Jin and Ji, 2008; Zhang, 2009)

and one from Malaysia (Lee et al, 2008).

The quality of studies ranged between 1 and 4 on the

Jadad scale. The study of Lee et al (2008) was well

designed in terms of randomization, partial blinding,

dropouts, and intention to treat analysis, and it used the

standardized National Institutes of Health Chronic

Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) as a primary

outcome. We scored this study as 4.

All of the Chinese-language studies were described as

randomized; however, only 3 of them reported the

methods of sequence generation (ie, ‘‘table of random

number’’ [He et al, 2004; He and Xu, 2007] and softwareStatistical Analysis System [Zhang, 2009]). None of the

Chinese RCTs described allocation concealment or

blinding procedures. None of the trials described dropout

rate or intention-to-treat analyses. Overall, the methodologic quality of the Chinese trials was poor (Table 1).

Other sources of bias in these studies included lack of

standardized/validated primary outcome measures, power calculations, clearly defined inclusion and exclusion

criteria, and adequately performed statistical analyses.

Additional threats to internal validity included lack of

appropriate sampling method, wide confidence intervals,

incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. None of these trials used placebo or sham

acupuncture to control adequately for nonspecific effects.

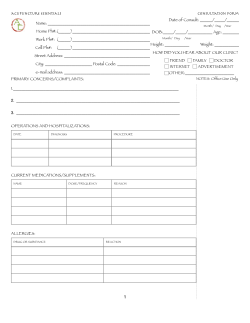

Eight Chinese-language studies used effective rate as

the primary outcome measure. According to the

different type of control treatments, the 8 articles were

classified into 4 subgroups (Figure). Needle acupuncture

treatments seem more effective than Pule’an pian (He et

al, 2004; He and Xu, 2007; Zhang, 2009), conventional

drugs for prostatic hyperplasia (Hu et al, 2005; Li and

Wang, 2006), antibiotics (Huang et al, 2005), or herbal

medicines (Wang, 1997; Jin and Ji, 2008).

Posadzki et al

N

Acupuncture for Prostatitis

17

Figure. Forest plots—effect of acupuncture for chronic nonbacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. M-H indicates Mantel-Haenszel.

Discussion

In their article, Wang and Han (2008) concluded that

‘‘acupuncture therapy exhibited a definite effect in the

treatment of chronic prostatitis.’’ Our evaluation

suggests that these conclusions are not supported by

the best available evidence. The review by Wang and

Han was wide open to bias. Therefore, our aim was to

provide a rigorous evaluation of the available RCT

data.

The 9 trials that met our eligibility criteria suggested

that acupuncture is effective for chronic CP/CPPS

(Wang, 1997; He et al, 2004; Hu et al, 2005; Huang et

al, 2005; Li and Wang, 2006; He and Xu, 2007; Jin and

Ji, 2008; Lee et al, 2008; Zhang, 2009). Thus, to some

extent we arrive at conclusions similar to those by Wang

and Han (2008). The important difference, however, is

that our results are based on higher quality and quantity

of the data.

Treatment groups received needle acupuncture

(Wang, 1997; He et al, 2004; Hu et al, 2005; Huang et

al, 2005; Li and Wang, 2006; He and Xu, 2007; Jin and

Ji, 2008; Lee et al, 2008; Zhang, 2009), whereas control

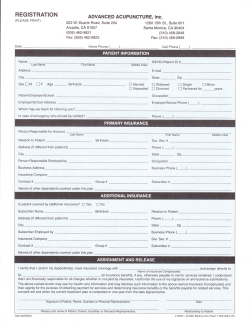

Table 2. Details of the acupuncture intervention

Author (Year)

He and Xu (2007)

He et al (2004)

Hu et al (2005)

Huang et al (2005)

Jin and Ji (2008)

Li and Wang (2006)

Lee et al (2008)

Wang (1997)

Zhang (2009)

Acupuncture Points Used (Direct Quote Where Appropriate)

1. Sanyin points; 2. Sanyin points plus Yinsan points, retaining needle for 30 min, 1 time per d, 30 treatments (36 d)

Sanyin points (points at perineum, named by the author) and other acupoints, retaining needle for 30 min, 1 time per d,

30 treatments (36 d)

CV3-to-CV2, BL32-to-BL34; BL54-to-BL35, retaining needle for 20 min, 1 time per d for 30 d

CV6, CV4, CV3, BL54, BL23, BL28, BL22, ST28, SP9, SP6, KI3, retaining needle for 20–30 min, 1 time per d. Total

treatment duration: 2–4 wk. (Not uniform for all patients)

BL54 to ST28. Other acupoints were selected individually according to the principle of traditional Chinese medicine.

Retaining needle for 30 min, 1 time per d, duration 2 mo

CV1 and CV3. Other acupoints were selected individually according to the principle of traditional Chinese medicine.

Retaining needle for 30 min, 3 times per wk, total treatment duration 8 wk

CV1 inserted with a depth of 50 mm, CV4 with 60 mm, and SP6 and SP9 with 40 mm. Two weekly sessions for 10 wk,

30 min each session

CV1. Duration: 1 time per d, without retaining needle, 4 wk (1 d stopping per wk)

BL54-to-ST28, retaining needle, 30 min per treatment, tertian treating, duration 8 wk

Study

Design

CP/CPPS

CP and

prostatodynia

CP

CP

CP

CP

Condition

90 (51/39)

89 (44/45)

60 (30/30)

84 (42/42)

90 (48/42)

115 (T1 40/T2

45/ C 30)

90 (60/30)

Sample Size

(T/C)

T: 21–52

(mean, 35)

C: 19–55

(mean, 33)

T: 40.9

C: 42.8

T: 25–50

(mean, 37.5)

C: 24–51

(mean, 37.5)

20–49 (mean

age, 32.98)

18–65

T1: 22–76

T2: 18–72

C: 20–72

T: 19–76

C: 20–72

Mean Age of

Participants or

Age Range, y

Needle

acupuncture

Acupuncture

Needle

acupuncture

Needle

acupuncture

Needle

acupuncture

Needle

acupuncture

Needle

acupuncture

Treatment Group

(Regimen)

Primary

Outcome

Measure

NIH-CPSI

Adverse Effects

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

Adverse effects occurred

in 13 participants, 8

(18.1%) in the

acupuncture group (6

hematomas and 2 with

pain at needling sites),

and 5 (11.1%) in the

sham group (1

hematoma, 3 with pain

at needling sites, and

1 with acute urinary

retention)

Pharmacotherapy 1. Effective rate No adverse effects

(terazosin

(in %)a

occurred in the

hydrochloride) 2. WBCb

treatment group; 2

3. The amount

cases of postural

of lecithin

hypotension occurred

lipophore in

in drug group

prostatic fluid

Sham

acupuncture

Sitz bath in

Effective rate

decoction of

(in %)a

herbal medicine

Pharmacotherapy Effective rate

(ofloxacin)

(in %)a

Pharmacotherapy Effective rate

(Cernilton

(in %)a

Prostat)

Pharmacotherapy Effective rate

(Pule’an pian)

(in %)a

Pharmacotherapy Effective rate

(Pule’an pian)

(in %)a

Control

Intervention

N

Open-label RCT CP

with 2

parallel

groups

To find effective Open-label RCT

remedies for

with 2

CP

parallel

groups

To find effective Open-label RCT

remedies for

with 3

CP

parallel

groups

To evaluate the Open-label RCT

effectiveness

with 2

of pointparallel

through-point

groups

acupuncture

for CP.

To evaluate the Open-label RCT

efficacy of

with 2

acupuncture

parallel

for CP

groups

To evaluate the Open-label RCT

efficacy of

with 2

acupuncture

parallel

for CP

groups

To compare

Patient-blind

‘‘the efficacy

RCT with 2

of acupuncture groups

to sham

acupuncture

for CP/CPPS’’

Objective

(Quote)

Journal of Andrology

Li and Wang To evaluate the

(2006)

efficacy of

acupuncture

for CP.

Lee et al

(2008)

Jin and Ji

(2008)

Huang et al

(2005)

Hu et al

(2005)

He and Xu

(2007)

He et al

(2004)

Author

(Year)

Table 3. Randomized clinical trials of acupuncture chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS)

18

January February 2012

b

Effective rate is the percentage of patients with improved status of disease divided by the sample size of each group and multiplied by 100.

The amount of white blood cells (WBC) in prostatic fluid after treatment.

19

a

Abbreviations: C, control group; NIH-CPSI, National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index; RCT, randomized clinical trial; T, treatment group; T1, acupuncture at Sanyin

points; T2, acupuncture at Sanyin plus Yinsan points.

No information

Elongatedneedle

acupuncture

T: 47.1

C: 45.1

104 (54/50)

Pharmacotherapy Effective rate

(Pule’an pian)

(in %)a

Two cases of hematuria

cased by acupuncture

and recovered 1 d

later.

Decoction of

Effective rate

Chinese herbal

(in %)a

medicine

T: 17–45 (mean, Needle

29.5);

acupuncture

C: 16–40

(mean, 28.5)

Adverse Effects

Condition

Acupuncture for Prostatitis

168 (84/84)

Primary

Outcome

Measure

Control

Intervention

Treatment Group

(Regimen)

Mean Age of

Participants or

Age Range, y

Sample Size

(T/C)

Study

Design

Objective

(Quote)

Author

(Year)

Table 3. Continued

N

Wang (1997) ‘‘To evaluae the Open-label RCT CP

efficacy of

with 2

needle

parallel

acupuncture

groups

for CP’’

Zhang

‘‘To evaluate the Open-label RCT CP

(2009)

effectiveness

with 2

of pointparallel

through-point

groups

acupuncture

for chronic

prostatitis’’

Posadzki et al

groups received pharmacotherapy (He et al, 2004; Hu et

al, 2005; Li and Wang, 2006; He and Xu, 2007; Zhang,

2009; Zhong-Xin, 2009), herbal medicine (Wang, 1997;

Jin and Ji, 2008), or sham acupuncture (Lee et al, 2008).

In order to lead to any firm conclusion regarding the

effectiveness of acupuncture superiority, RCTs need to

control for placebo effects. Only one study made serious

attempts to do this (Lee et al, 2008). Equivalence trials

can only lead to interpretable results if they compare the

experimental treatment against an intervention of

proven efficacy. Unfortunately, all of the Chinese

studies failed to do so, and therefore no firm conclusions

can be drawn from such studies.

The exact psychologic or other mechanisms of action

of acupuncture remain unclear (Lewith and Kenyon,

1984; Kavoussi, 2009).Whether certain patient groups

respond to acupuncture differently than others and

whether suggestibility is an essential factor for any

response remain unclear. The possible mechanism of

action may therefore include the patients’ expectations—a part of the placebo effect (Dawn and Lee,

2004; Verbeek et al, 2004). Patients have explicit

expectations on diagnosis, instructions, interpersonal

management, or course of treatment (Verbeek et al,

2004), and they expect that these expectations will be

met (Dawn and Lee, 2004). Recently, it was shown that

the communication style of the acupuncturist is a more

important determinant of the response than the question

of whether a patient receives real or sham acupuncture

(Suarez-Almazor et al, 2010).

All of the Chinese language RCTs included effective

rate as a primary outcome measure, and one of those

trials also used white blood cell level and the amount of

lipophore in prostatic fluid (Li and Wang, 2006). Only

one RCT used standardized NIH-CPSI (Lee et al, 2008).

There was also a wide variety of acupuncture points

used in the treatment groups (Table 2). The duration of

therapeutic intervention ranged from 2 to 4 weeks

(Huang et al, 2005), 1 month, (Wang, 1997; He et al,

2004; Hu et al, 2005; He and Xu, 2007), and 2 months

(Li and Wang, 2006; Lee et al, 2008; Jin and Ji, 2008;

Zhang, 2009). Given such variability in terms of length

and diversity of the therapeutic intervention, it is

difficult to draw any definite conclusions.

The quality of the included studies was predominantly

poor. Eight (88.8%) scored less than 2 on the Jadad scale

(Wang, 1997; He et al, 2004; Hu et al, 2005; Huang et al,

2005; Li and Wang, 2006; He and Xu, 2007; Jin and Ji,

2008; Zhang, 2009). Only one RCT scored 4 on the

Jadad scale (Lee et al, 2008). Five Chinese RCTs

(55.5%) failed to describe sequence generation sufficiently (Wang, 1997; Hu et al, 2005; Huang et al, 2005;

Li and Wang, 2006; Jin and Ji, 2008). None of the

Chinese RCTs described allocation concealment or

20

blinding procedures. None of the Chinese trials described dropout rates or included an intention-to-treat

analysis or a power calculation.

Adverse events (AE) were not reported in most trials

(Table 3; He et al, 2004; Hu et al, 2005; Huang et al,

2005; He and Xu, 2007; Jin and Ji, 2008; Zhang, 2009).

Three RCTs reported the incidence of AEs (Wang, 1997;

Li and Wang, 2006; Lee et al, 2008). STRICTA

guidelines, and indeed medical ethics, require the

reporting of AEs. Underreporting distorts the overall

picture of what we know about the safety of acupuncture.

Our review has several limitations. First and foremost, the potential incompleteness of the reviewed

evidence may have limited the validity of the results.

Second, publication and location biases, which are wellknown phenomena, may also influence the results of this

systematic review. Third, the total number of trials

included in our review and analysis, and the total sample

size are too small to allow definitive judgments. Fourth,

although all of these studies were considered to have

relatively homogenous CP/CPPS populations, statistical

pooling was not possible because of lack of reporting of

sufficient raw data. Another possible source of bias is

the fact that almost all (88.8%) of the included trials

were carried out in China, where they have appeared to

produce almost no negative studies (Vickers et al, 1998).

However, this review has several strengths, including the

comprehensive search strategy, the inclusion of only the

highest-quality trial design, and use of suggested

methods for systematic reviews of interventions for

CP/CPPS.

Future studies of acupuncture in CP/CPPS should be

of adequate sample size based on power calculations;

provide sufficient details on needling, frequency, duration

of therapeutic regimen, and practitioners’ background;

use validated outcome measures; control for nonspecific

effects; and minimize other threats to internal and

external validity. Reporting of these studies should be

such that results can be independently replicated.

In conclusion, the evidence that acupuncture treats

CP/CPPS is encouraging. However, the quantity and

quality of the existing evidence prevent firm conclusions.

References

Anothaisintawee T, Attia J, Nickel JC, Thammakraisorn S, Numthavaj P, McEvoy M, Thakkinstian A. Management of chronic

prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome a systematic review and

network meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:78–86.

Capodice JL, Bemis DL, Buttyan R, Kaplan SA, Katz AE.

Complementary and alternative medicine for chronic prostatitis/

chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Evid Based Complementary Altern

Med. 2005;2:495–501.

Journal of Andrology

N

January February 2012

Chen R, Nickel JC. Acupuncture ameliorates symptoms in men with

chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2003;

61:1156–1159.

Collins MM, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of

chronic abacterial prostatitis: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med.

2000;133:367–381.

Dawn AG, Lee PP. Patient expectations for medical and surgical care:

a review of the literature and applications to ophthalmology. Surv

Ophthalmol. 2004;49:513–524.

He TY, Xu YL. Clinical observation on acupuncture at ‘‘sanyin

points’’ plus ‘‘yinsan points’’ for treatment of chronic prostatitis.

World J Clin Acupunct Moxibust. 2007;23:12–13.

He TY, Zhao YD, Luo CL. Clinical observation on acupuncture at

‘‘sanyin points’’ for treatment of chronic prostatitis. Chin Acupunct

Moxibust. 2004;24:697–698.

Honjo H, Kamoi K, Naya Y, Ukimura O, Kojima M, Kitakoji H,

Miki T. Effects of acupuncture for chronic pelvic pain syndrome

with intrapelvic venous congestion: preliminary results. Int J Urol.

2004;11:607–612.

Hu BC, Wang S, Zhou ZK, Cai YY. Point-through-point acupuncture

for the treatment of chronic non-bacterial prostatitis. Cap Med.

2005;18:47.

Huang YJ, Fan XH, Du M. Acupuncture for the treatment of

chronic prostatitis in 42 cases. J Acupunct Moxibust. 2005;21:

8–9.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carrol D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ,

Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of

randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clin

Trials. 1996;17:1–12.

Jin XH, Ji LX. Clinical study on acupuncture for the treatment of

chronic non-bacterial prostatitis and prostatodynia. Chin Naturopath. 2008;5:9.

Kavoussi B. The untold story of acupuncture. Focus Altern Complementary Therapies. 2009;14:276–285.

Lee SH, Lee BC. Electroacupuncture relieves pain in men with chronic

prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: three-arm randomized

trial. Urology. 2009;73:1036–1041.

Lee SW, Liong ML, Yuen KH, Leong WS, Chee C, Cheah PY,

Choong WP, Wu Y, Khan N, Choong WL, Yap HW, Krieger JN.

Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture for chronic prostatitis/

chronic pelvic pain. Am J Med. 2008;121:79.e1–e7.

Lewith G, Kenyon J. Physiological and psychological explanations for

the mechanism of acupuncture as a treatment for chronic pain. Soc

Sci Med. 1984;19:1367–1378.

Li C, Wang HS. Clinical study of acupuncture for the treatment

of chronic prostatitis. Beijing J Tradit Chin Med. 2006;25:680–

681.

Li ZG. Electro-acupunture for the treatment of chronic prostatitis in

60 cases with observation on the valure of Zn, Cu, SOD. Chin J

Tradit Med Sci Technol. 2005;12:401.

Murphy AB, Macejko A, Taylor A, Nadler RB. Chronic prostatitis

management strategies. Drugs. 2009;69:71–84.

Suarez-Almazor ME, Looney C, Liu Y, Cox V, Pietz K, Marcus DM,

Street RL Jr. A randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for

osteoarthritis of the knee: effects of patient-provider communication. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:1229–1236.

Verbeek J, Sengers MJ, Riemens L, Haafkens J. Patient expectations

of treatment for back pain: a systematic review of qualitative and

quantitative studies. Spine. 2004;29:2309–2318.

Vickers A, Goyal N, Harland R, Rees R. Do certain countries produce

only positive results? A systematic review of controlled trials.

Controlled Clin Trials. 1998;19:159–166.

Wang C, Han R. Acupuncture for chronic prostatitis: a meta-analysis.

Natl J Androl. 2008;14:853–856.

Posadzki et al

N

Acupuncture for Prostatitis

Wang RS. Clinical observation of acupuncture in Huiyin points for the

treatment of chronic prostatitis in 84 cases. Chin Acupunct

Moxibust. 1997;7:397–398.

Yu Y, Kang J. Clinical studies on treatment of chronic prostatitis with

acupuncture and mild moxibustion. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25:

177–181.

21

Zhang XJ. Observations on the efficacy of point-through-point

acupuncture with elongated-needle in treating chronic prostatitis.

Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibust. 2009;28:589–590.

Zhong-Xin C. Observation of therapeutic effect on chronic nonbacterial prostatitis treated with warm needling moxibustion.

World J Acupunct Moxibust. 2009;19:19–29.

© Copyright 2026