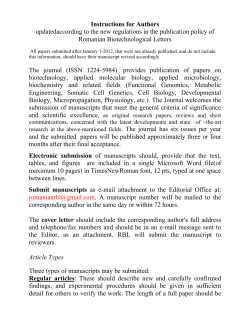

How to Write a Paper www.ATIBOOK.ir