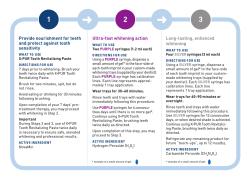

Chairside