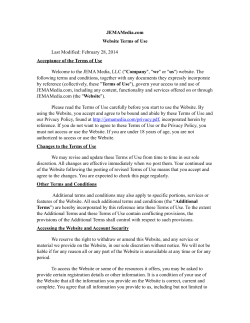

NOTE LOOK OVER YOUR FIGURATIVE SHOULDER: HOW TO SAVE INDIVIDUAL DIGNITY AND