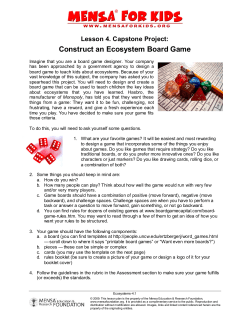

how schools work how to work with schools &