Document 191185

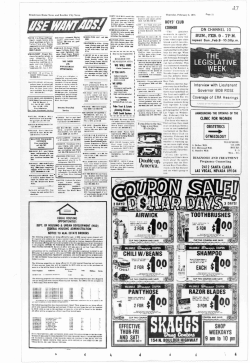

How To Manage Radical Innovation Robert Stringer Three of the people attending the meeting in a Chicago suburb were going broke. They had spent most of their money and all of their time for the past two years trying to commercialize a radical innovation called "Liquid Life," an all-natural beverage made 100% from pureed fruit. They had developed an attraaive plastic package, six good tasting flavors, and eye catching point-of-sale promotional materials. Grocery stores had told them they loved the idea and would gladly carry the product. However, consumers knew nothing about "Liquid Life" and it would take millions of dollars to cormnercialize the innovation the way the three entrepreneurs wanted to do it. Now, they had run out of money and time. Four other people were at the meeting. Two were investment bankers, one a venture capitalist, and one a vice-president from Big Food, Inc., a Fortune 100 food and beverage company. Three of these four tried, once again, to convince the "Liquid Life" entrepreneurs to sell their ideas and technology to the food company. Once again, this advice was met with an emotional refusal. The argument was always the same: the food company loved the breakthrough technology and was desperate for a radical new idea that might pump life into one of its existing product categories, but they could not pay much for an unproved innovation. The "Liquid Lifers" loved the idea of having a big company's resources behind them, but they knew the food company would strangle their commercialization dreams and control the way they developed future products. None of them wanted to join a large—though very successful—^public company. The investment bankers had brought the food company to the meeting and advised the "Liquid Lifers" to sell. The venture capitalist wasn't so sure. This scene is played out every week. Entrepreneurs see opportunities to introduce radical innovations and they act on this opportunity. Their analysis may not be complete, but they are committed to action and they learn by doing. Often, it is an expensive lesson. Large companies in traditional industries, on the 70 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation Other hand, may realize that their industries are suddenly changing and that the winners in the new millennium will be those who adapt the quickest and innovate most effectively, but they do not know how to do this. They seem to be "genetically" incapable of commercializing radical innovation, and they cannot bring themselves to learn by doing. Innovation Is a Strategic Imperative Not surprisingly, history tells us that most large companies are not radical innovators. They are good at making close-in changes to existing products or technologies, but they do not often commercialize breakthrough ideas. According to Marketing Intelligence Service's Innovation Ratings, more than 25,000 new consumer packaged goods were launched in 1998, most of them by large compahies. Over 93 percent of these were judged to be "not significantly innovative."' Corporate size is inversely correlated to growth through innovation. Historically, the Small Business Administration estimates that small firms have produced 2.4 times as many innovations per employee as large firms.^ A recent Harvard and Boston University study of 20 U.S. industries from 1965 to 1992 discovered that small companies supported by venture capital produced six times as many patents as a similar amount of traditional corporate R&D spending.' Another recent study of the growth records of the Fortune 50 sponsored by Hewlett-Packard and the Corporate Strategy Board concluded that the single biggest growth inhibitor for large companies was "mismanagement of the innovation process."" The recent emergence of the e-business model places an even greater premium on the ability to quickly commercialize radical innovation. In the age of the Internet, information—about new technologies, new applications, new research results, product performance, customer experiences, and competitive reactions to new ideas—is increasingly available to everyone. Not only is there an ever-larger array of radical new value propositions for both buyers and sellers, the need for speed in finding, assessing, and commercializing innovative ideas is dramatically increased. In an e-world that runs on e-time, speed to market is measured in days and weeks. A conservative and deliberate company will find it hard to survive, much less prosper, in the world of e-business. Though the world demands more innovative organizations and the largest U.S. companies want to be innovative, most are poorly equipped to implement a growth strategy based on radical innovation because most large companies are genetically programmed to preserve the status quo. They do not have the right organization, culture, leadership practices, or personnel to collect and successfully commercialize radical new ideas. In addition, when they are exposed to entrepreneurs who have potentially profitable breakthrough innovations, they do not seem to learn fast enough and well enough to take full advantage of the exposure and the innovations. CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 71 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation Why Aren't Large Companies More Innovative? This genetic conservatism and learning deficiency underlie the four reasons why large companies find it so hard to successfully embrace and commercialize radical innovations. Industry Leaders Can't Afford to Embrace Radical Innovation Powerful economic and strategic barriers prevent many large companies from being the "first movers" who introduce radical innovations to the marketplace. Clayton Christensen, in his award-wirming The Innovator's Dilemma, explains the difference between "sustaining" and "disruptive" technologies and points out how poorly equipped industry leaders are to cope with radical or disruptive innovation.' Sustaining technologies foster improved performance of existing products or services. Industry leaders must (and usually do) invest heavily in sustaining technologies. When disruptive technologies emerge in an industry, they may lead to worse product performance for mainstream customers, even though the radical innovation often embodies a new and improved value proposition for rapidly growing segments of non-mainstream customers. Industry leaders find it hard to embrace emerging, non-traditional technologies because it costs them too much money. The larger their market share, the more they feel they have to lose. The economics of radical innovation impairs their vision in two ways. First, leaders cannot "see" the long-term potential of the new technology because the very basis of competition changes. Second, even if an industry leader recognizes the fundamental shift, it is difficult for the company to reallocate resources fast enough to capitalize on the opportunity. This gives industry leaders mixed motives. They sense the world is changing, but they have too much invested in the status quo to embrace the radical innovation. They prefer to focus on making incremental improvements to their core technologies. Structures and Cultures Discourage Bringing Big Ideas to Market Size and shape make a difference. Large scale, while often a powerful source of competitive advantage, leads to bureaucratic structures that discourage bringing breakthrough or radical innovations to market. The brand management organization in most consumer goods companies encourages short-term thinking and incremental product improvements, not breakthrough ideas. Radical innovations often require dramatic shifts in production capabilities, distribution mechanisms, or customer relationships. These shifts threaten the status quo and upset the hierarchy and social systems that have contributed to the large company's past successes. The cultures of most large companies act as powerful stabilizing influences. Exploiting and commercializing radical new ideas, especially when they threaten to sweep away the old order of things, destabilizes the organization. Inventions that are considered isolated "good ideas" will be tolerated. 72 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation often encouraged, but rapid and widespread commercialization of an untested and unproved new idea is another matter. Relying Too Much on Internal Relying on ever-larger internal R&D budgets to keep abreast of all of the potential breakthrough ideas has not worked in the past. There is no reason to believe it will work with all the new technologies and business models being introduced today. Internal R&D projects cannot possibly anticipate or support all of these emerging designs all the way to the marketplace. During times of rapid change, industry leaders who want to stay leaders need to place multiple bets on a wide range of promising innovations. Furthermore, they need to see how these new ideas work outside of the laboratory. The real worth of a radical innovation can only be calculated after real customers make real purchase and use decisions over time. Most R&D departments have limited responsibility for the start-to-finish commercialization process, so pouring more money into internal R&D is not the answer. To complicate the industry leaders' R&D dilemma even more, they must continue to invest in their existing technology. To stay on top, they must constantly develop their existing products and services, while at the same time engaging in robust search and learning behaviors that allow them to quickly discover, influence, or respond to the emerging technology or business model. These multiple demands on internal R&D inevitably put pressure on the budget. Many large companies have responded to this pressure by decentralizing R&D. All this does is ensure that immediate sales and marketing needs will take precedence over longer-term investments in radical innovation. Even in a centralized R&D function, industry leaders must be very careful about prematurely assuming a new technology will be the best solution and committing the company to it. Unless they "keep their powder dry" as long as possible before making a large investment in a radical innovation, they run the risk of being stuck with a bad idea. All of this is a tall order for any internal R&D department, no matter how well funded, how well managed, or how well positioned in the strategic decision making process of the corporation. Traditional methods of evaluation of the portfolio of internal R&D projects (e.g., discounted cash flow analysis) also serve to inhibit the comimercialization of radical innovations. The criteria used to judge radically new ideas are generally subject to the same short-term biases and constraints as other investments. The resulting pattern of innovation tends to support close-in, incremental change, but it will not generate a significant flow of fully developed breakthrough ideas. A classic example of this problem was played out at IBM. If it had not been for Bernard Meyerson, one of IBM's research fellows, the development of silicon-germanium semiconductors would have been aborted back in the early 1980s. According to all of IBM's sophisticated portfolio analyses, this project was never going to make sense. Meyerson kept it alive, largely by ignoring the mathematical logic of this analysis. Often working on a shoestring budget, he fought CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 73 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation for years for silicon germanium in the face of supposedly more feasible R&D projects in IBM's R&D portfolio. The internal battle for support for radical ideas must have been fierce at IBM. Meyerson himself admits he was following the advice of a former IBM president who, wise in the ways of corporate bureaucracy, said: "If a senior executive hasn't screamed at you lately for grossly exceeding your authority, you're probably not doing your job."* There is a strong logic for saying that the evaluation and funding of breakthrough R&D should be separated from a large company's normal R&D decision-making processes. In order to avoid the trap of incremental thinking, all aspects of breakthrough innovation must be carved out; this includes identifying promising radical innovations, funding them, testing them, screening them, and commercializing those that make sense. However, if you separate accountability for introducing radical innovations, how do you maintain control? How does the large company know when a development project is to be considered breakthrough? These become sensitive political issues. How can a large company give up control over even part of its investment in R&D? After all, that control is the whole point of the internal R&D portfolio management process. Large Companies Don't Attract or Retain Radical Innovators Research shows that the motivational profile that is most likely to be successful in a large corporate environment is one dominated by the need for power, not the need for achievement.^ Social skills—including the ability to influence others, the patience to work across organizational boundaries, and the mastery of the political aspects of organizational life—count for more than having an aggressive competitive spirit. Innovators tend to be high achievers, and they are attracted to working environments where they can "call the shots" and be individually responsible for results. Smaller companies offer far more opportunity for innovators to satisfy their needs for achievement. Large corporations may have their fair share of "inventors," that is, people who have new, creative ideas, but they do not nurture or motivate "innovators," people who take creative new ideas and make them into commercially successful products. This fundamental difference in motivational capacity is one reason why small companies commercialized more innovations in the 20th century, and it is why they will continue to do so in the next. Why Are Small Companies the Source of Most Radical Innovations? Small companies succeed in introducing more radical innovations because of their genetic makeup. Often, the entire organization can be built around a single breakthrough concept. Therefore, they have little emotional or economic investment in the status quo. In fact, they often see themselves as being at war with the existing order of things. Unlike their large company counterparts, the 74 CAUFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation leaders of small companies with a radical new technology will often bet most of their limited resources on commercializing the innovation. Just like the opening example of "Liquid Lifers," they may knowingly risk the enterprise trying to prove out and expand the viability of a new idea. Small company R&D functions are sometimes subject to the same conflicts as large company functions, but their small size puts them closer to the market and makes them more agile, less bureaucratic, and more responsive to the unpredictable nature of the commercialization process. The most important aspect of the small company genetic makeup, however, is the concentration of inventive entrepreneurs found in them. Because of who they are and where they work, these entrepreneurs can be ruthless about listening to the market and adapting their ideas in order to make them successful. Researchers have known for many years what motivates entrepreneurs. In the 1960s, we called it "achievement motivation."* A recent article in Fortune magazine labeled it the "need for accomplishment."' However it is described, the phenomenon is the same. Innovators and entrepreneurs are driven by four needs: • to compete against an internal standard of excellence, • to make a unique contribution to the world, • to engage in activities perceived to be moderately risky (that is, where the chances of success are close to 50/50, rather than impossibly difficult or too easy), and • to constantly receive concrete, measurable feedback on their performance and progress. High achievers are planners. Aware of things that will hinder their progress, they constantly search for ways to overcome these obstacles. They seek (and are motivated by) tangible feedback rather than vague or hard to understand measures. They learn from this feedback. They art on it. High achievers are not simply idea people—they are builders. They take ideas and put them to work, and this is what makes them successful as entrepreneurs. Unfortunately, entrepreneurs often have well-earned reputations for being poor team players. They view other people as a means to an end, and they can be stubborn, ruthless, and driven—not by fame or fortune, but by their need to accomplish something real, meaningful and tangible. As Fortune states, "Entrepreneurs with the right stuff don't think much about taking risks or getting rich. Instead, they are obsessed with building a better mousetrap."'" It is not hard to imagine why large company environments frequently discourage and de-motivate entrepreneurs who are the drivers of radical innovation: too many rules, too much compromise, too many meetings, and too little willingness to "just do it." CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 75 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation Stimulating Innovation in Large Companies Given this picture of the kind of people most likely to commercialize a radical new invention and stick with a "crazy idea" until it either succeeds or fails, how have large companies tried to alter their own genetic code? How have large companies tried to attract and motivate entrepreneurs? How have they tried to reconcile the conflicting interests of those who want to innovate for tomorrow and those who want the profit for today? Moreover, why have they so often failed? Successful innovators use nine different strategies to attack the problem. They are listed below in the order of their potential for generating radical innovation and their usefulness in dealing with rapid industry and technological change. Unfortunately, the order also reflects what might be called "the degree of desperation." The first two or three are relatively conventional initiatives that are easier to implement but unlikely to generate a wealth of breakthrough innovation. The next few are harder to structure and more difficult to manage, but they have more potential for driving radical innovation in industries that are rapidly evolving. The final group of strategies are even more radical approaches that are quite risky and much harder to implement but more likely to result in big ideas that are commercially viable in emerging new industries. Working From the Inside Out The first five strategies have been employed by large companies who believe they can significantly increase the flow of radical innovation by working with their existing resources and organization. These strategies attack the problem of stimulating innovation with incremental investments, formal policies, and leadership. Strategy #1: Make breakthrough innovation a strategic and cultural priority. Talk about the need for new products and unconventional thinking. Set stretch goals that can only be achieved by doing things differently. Challenge business units to increase the percentage of their revenues derived from new products or services. Generate benchmark measures that show how important radical innovation is likely to be in your industry. Publicly highlighting the performance gap caused by the lack of big ideas and radical innovation creates a sense of urgency that often stimulates increased entrepreneurial activity, even in conservative companies. General Mills has been able to out-innovate its archrival Kellogg by constantly emphasizing the need for innovation in its cereal division, as well as its corporate strategy. The problem with this strategy is that it seldom works very well on its own. It is not enough to exhort people to support big ideas. Organizations that have consistently innovated combine the rhetoric with one or more of the other strategies. 76 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation Strategy #2: Hire more creative and innovative people. Although this initiative can be frustrating and expensive, there is little doubt that new blood tends to invigorate an old-line organization. Years ago, when Citibank decided to expand its consumer businesses in the Western Hemisphere, Ed Hoffman (then the president of the Western Hemisphere Consumer Group) recruited a cadre of entrepreneurial consumer products executives and challenged them to "break the rules." He wanted them to apply their consumer goods experience to the more conservative world of banking. Known around the WHCG as the "dog food managers" (several of them had come from General Foods, maker of Pet dog food), they successfully introduced a number of radical innovations to Citibank's portfolio of consumer products. Few of these executives remain today at what is now known as Citigroup. Bringing in radical innovators can stir up the organization's creative juices, but generating a stream of commercially viable breakthrough ideas takes more than the individual efforts of a few high achievers and entrepreneurs. At Citibank, when the real estate crises of the early 1990s put pressure on the bottom line, the "dog food managers" found that the bank's appetite for innovation was very limited. Strategy #3: Grow informal project laboratories within the traditional organization. Grant innovators free time to invent by building flexibility and fat into R&D budgets and by modifying the performance management system so that "crazy" new ideas that do not have immediate payoffs are not punished. The concept of informal project laboratories is at the heart of 3M's success at innovating. Made famous in the early 1980s by Peters and Waterman's bestseller. In Search of Excellence, the story of innovation at 3M is impressive. One can only wonder if the more recent decline of radical new products from 3M is, in part, a result of their emphasis on cost cutting and the possible reduction of project lab budget flexibility. The biggest problem with the project labs strategy is that it flies in the face of what is believed to be good management practice. Leaving "fat" in budgets and looking the other way when scientists fail to justify their project expenditures or when researchers do not account for their time are not the habits of traditional well-run companies. Even in organizations where project labs find a life, it is often difficult to commercialize the innovations that are generated. Surinder Kumar, the former head of R&D for the Pepsi-Cola Company, can attest to this. He used to encourage innovation, especially radical new approaches to certain aspects of Pepsi's technology, but only those projects that met rigorous evaluation criteria were ever funded for commercial or market testing." CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 77 How To Manage Radical Innovation Strategy #4: Create "idea markets" within the organization. Establish autonomous teams, called "idea markets" or "knowledge markets," to identify and commercialize radical innovations. Traditional companies like Royal Dutch/Shell Group, Nortel, and Procter & Gamble are more and more frequently putting together small teams of volunteer internal entrepreneurs and charging them with the responsibility for driving radical innovation. Funded separately from the traditional R&D budget, these teams collect the best ideas from throughout the corporation and independently develop and commercialize those that make the most sense. The World Wide Web allows these idea markets to flourish across geographic and organizational boundaries with decentralized resources, greatly reducing the bureaucratic constraints on the teams. At Royal Dutch/Shell, idea market teams (known as GameChangers) have stimulated over half of the company's top business initiatives for 1999. Idea markets are not as easy to manage as traditional project labs. The most effective programs create truly autonomous teams and allow these teams to control their own destinies. They hire their own people, are free to tap into the corporation's resources, write their own rules, and often report directly into the CEO. Rewarding idea market team members is, perhaps, the most significant challenge. Nortel uses "phantom stock" to compensate those who.volunteer for special, high-risk projects, and it agrees to "buy" these projects as if they were independent companies and were going public. Not surprisingly, it is easier to use the idea market strategy as a source of breakthrough concepts than it is to use them as the vehicle for commercializing the innovations. For this reason, most companies pass off the responsibility for implementing the idea market projects to established business units. This has not always worked because the greatest barriers to innovation are often found at the business unit level. Recognizing this, P&G's CEO Durk Jager has put aside $250 million of seed money to fund a centralized and independent Corporate New Ventures division that he hopes will stimulate breakthrough innovation in the new millennium. Like many of its big company peers, P&G needs to find a new approach to innovation management. The company has not introduced a new product line since 1983. Strategy #5: Become an "ambidextrous organization." This is a strategy described and advocated by Michael Tushman and • Charles O'Reilly in their recent book. Winning Through Innovation. They define technology life cycles and innovation in terms of "streams" and explain how a selected few large companies have managed to create two different organizations under one roof to manage these streams. One is dedicated to maximizing the value of the traditional technology, the other to commercializing radical innovation. Tushman and O'Reilly are quick to point out the difficulties with such dual strategies: "The contradictions inherent in the multiple types of innovation create conflict and dissent between the organizational units—between those 78 CAUFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 H o w To Manage Radical Iniiovation historically profitable, large, efficient, older, cash-generating units and the young, entrepreneurial, risky, cash-absorbing units."'^ How do these authors say that these difficulties should be overcome? How should their "ambidextrous organizations" be created and managed? First, keep the radical innovators completely separate from the traditionalists who run the core business. "The management team must not only protect and legitimize the entrepreneurial units, but also keep them physically, culturally, and structurally separate from the rest of the organization."'' Second, try to leverage the radical innovation for the benefit of the total company. This, they admit, is the hard part. Unfortunately, their guidelines for integrating radical innovation into the fabric of the large corporation are not always crisp and clear. According to Tushman and O'Reilly, the most important tool for dealing with the conflicting interests of the two parts of the organization is having a clear vision for the total business. When Seiko defines its mission in terms of being in the "watch business," not just the "mechanical watch business," it can more easily accept, exploit, and integrate the radical innovation of quartz watch movements. They quite correctly point out that the problem is the same as when the railroads denied they were in the transportation business. In other words, the answer to the lack of foresight about radical innovation is to have greater strategic foresight. Tushman and O'Reilly also stress the importance of having a highly skilled senior leadership team. "In managing streams of innovation, senior teams are like jugglers, keeping several balls in the air at once—articulating a single, clear vision while simultaneously hosting multiple organizational architectures without sounding confused or, worse, hypocritical. Most management teams can do one thing well, but keeping a multitude of activities going at once requires greater skill."'" Perhaps the reason why Tushman and O'Reilly's guidelines are somewhat fuzzy is because the task is so daunting. When attempting to implement any of these five strategies, innovation-starved companies soon realized the difficulty of altering what is inside their organization's boundaries. More recently, old-line companies trying to compete in rapidly changing industries have looked more to the outside to stimulate radical innovation. Working From the Outside In Strategy #6: Experiment with acquisitions, JVs, cooperative ventures, and alliances with outside innovative entities. The first external strategy that stodgy companies have tried to employ is to acquire or purchase radical innovation. If. innovations could not be bought, large companies tried to form alliances and hybrid ownership arrangements with innovators. Unfortunately, most mergers, acquisitions, JVs, and other kinds of external alliances have failed to generate an ongoing stream of commercial CAUFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 79 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation breakthroughs. The innovation-hungry company usually saw itself as acquiring a new product, rather than acquiring a new capability. Even when they realized that the radical innovation involved more than a specific product, they did not know how to learn about the capability. Too often, when this was the case, the acquisition or alliance created less, not more, innovation in the core business." In addition to the failure to learn from the alliance or acquired partner, the stumbling block frequently turned out to be the structure, culture, and bureaucracy of the company desperate to innovate. Time and again, promising new products or technologies proved to be too radical, too threatening, or too different to be developed to their full commercial potential or to be leveraged back into the company's base business. A classic example of this was illustrated by the experience of Quaker Oats. Competing in the slow growth food industry, Quaker wanted to innovate in beverages. After all, they dominated the sports drink market with Gatorade. In 1994, Snapple was acquired with high hopes. Three years later, it was sold for $300 million—a shocking $1.4 billion less than what they had paid for it. On occasion, the big company simply drove away the entrepreneurs and innovators by attempting to guide, control, or influence the commercialization of their ideas. In other words, innovation-seeking industry leaders looked outside but kept trying to bring the innovations inside. Their focus on control and ownership of the innovations and the innovators, though appealing to the large company mentality, not only did not produce the desired stream of new commercial successes, it inhibited that stream by providing a false sense of progress. Even though the track record for an innovation-by-alliance strategy is discouraging, it makes good sense as part of an overall program of innovation management. High-technology companies have employed this approach with greater success than large companies in other industries. Cisco Systems, Intel, Microsoft, and Hewlett-Packard have demonstrated that you do not have to own a big idea to benefit from it. They have spent a lot of time and energy figuring out how to manage their external partnerships, not just how to negotiate them, and this may account for their higher success rate. Peter Cohan, in his recent book. The Technology Leaders, outlines how these companies do it. They take the following steps: • Make sure the partners share common objectives. • Assign respected executives from both companies to be accountable for the venture's success. • Build joint teams to enhance knowledge transfer and mutual trust. • Develop a clear business plan for the joint venture. • Link people's incentives to the success of the partnership. • Pay attention to the people issues, especially the need to effectively resolve conflicts. • Develop a common understanding of how the alliance will end.'* 80 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation Strategy #7; Engage in corporate venturing. Corporate venturing—creating and supporting new businesses that are managed apart from a company's existing business—is another strategy that can be employed to stimulate radical innovation. Corporate venturing departments take internal resources and attempt to treat them as if they were external resources. A few select companies—^Teradyne, Sun Microsystems, and Intel, for example—have succeeded in driving their growth agenda by means of corporate venturing, but the successes have been discouragingly rare. The most thorough review of corporate venturing is Zenas Block and Ian MacMillan's Corporate Venturing. These authors highlight the fact that most successful corporate ventures involve incremental, not radical, innovation, and they use Gannett's creation of USA Today as an example. Although USA Today involved new printing technology and a new approach to marketing, Gannett leveraged many of its existing capabilities in launching USA Today. Block and MacMillan emphasize how difficult it is to commercialize breakthrough ideas within the typical big company's corporate venturing structure. All the tenets of good corporate governance drive large companies to over control their captive ventures, managing them as little more than extensions of the internal R&D function. Venture division managers, corporate executives, and boards of directors are accountable, and this puts obvious limits on the independence of any venture sponsored by the company. The task of managing truly breakthrough ideas in a corporately sponsored new venture is so complicated that Block and MacMillan devote over 30 pages of their book to describing various ways to link radical innovations to the sponsoring firm without ruining the venture.'^ Traditional large companies want to own the most promising radical innovations they sponsor. This ownership mentality leads them to focus on the formal, contractual, and legal aspects of the relationship, paying less attention to those aspects that cannot be codified. Unfortunately, legal ownership of a new idea is only part of its potential value. Most new technologies, products, and services do not become commercial successes without applying a wealth of noncodified knowledge. It is often the informal conversations between the sponsor and the venture that create real understanding of what is required to commercialize a radical innovation. Most big companies concentrate so much on owning and controlling things, they do not attempt to learn from the ventures they sponsor. Block and MacMillan stress the importance of learning, stating emphatically: "In organizing a venture, learning remains the primary challenge, and the new business should therefore be organized in such a way as to maximize learning."'* Ironically, Block and MacMillan are referring only to the venture's ability to learn from the big company. However, their examples, guidelines, and advice are aimed in the wrong direction. The semi-independent status of a corporately sponsored venture is not good enough for most innovators and entrepreneurs. The proof of this lies with the experience of entrepreneurs who have sought corporate funding for their radical innovations. One successful innovator in the health care field fiatly stated CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEVV VOL. 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 81 How To Manage Radical Innovation that "corporate money has no clue what makes a breakthrough innovation really successful. Even sophisticated corporate venturers can't stay out of our way long enough to commercialize the idea the way it should be. They place all sorts of demands and unrealistic constraints on us. I guess these make sense from their point of view, but they make little sense from ours!"" Working with Venture Capital If small companies are more suited to the task of successfully commercializing radical innovations, recent research has shown that being small and agile is only part of the reason for their success. Commercialization of radical new ideas requires a special kind of partnership—^partnering with independent venture capitalists. A recent study by Thomas Hellmann and Manju Puri of Stanford University's Graduate School of Business demonstrates that venture capital support plays a critical role in bringing innovative ideas to market.^" Their examination of 170 emerging companies in Silicon Valley from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s finds that high innovators tend to use independent venture capital funding and tend to bring their products to market far faster than those companies that do not align themselves with venture capital firms. They also find that venture capital funding does not speed up the launch time of incremental innovations (what they label as "imitator" companies). In other words, radical innovation goes hand in hand with venture capital. The support that independent venture capitalists offer involves more than money. "Particularly through their active participation on company boards, venture capitalists provide critical guidance and help recruit key managers," says Hellmann.^' With the value of venture capital in mind, large companies are now experimenting with two additional external strategies to generate more radical innovation. Strategy #8: Establish a corporate venture capital fund. This involves putting aside a pool of money specifically earmarked for investments in start-up enterprises in fields related to the company's growth strategy. Block and MacMillan point out that the track record of such corporate venture capital funds has been mixed, and they state that the single biggest reason for failure has been the lack of clarity regarding the mission of the corporate venture capital activity. Does it exist to support the big company's R&D and market expansion plans or does it exist to support the interests of the portfolio companies?^^ J&J Development Corporation (JJDC) is one of the best examples of a relatively successful corporate venture capital initiative. JJDC has been doing venture investing since 1973 and has accumulated 25 years worth of practical experience. JJDC executives observe, among other things, that issues of control and independence are very important for most entrepreneurs, who are afraid of losing control of their operations and the theft of their ideas. Over the years, JJDC's outstanding corporate reputation, along with hard protective work by 82 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation JJDC executives, have partially overcome these fears. Qther venture capitalists are also wary of corporate venture capitalists, in part because sponsoring corporations are impatient with the long time franies venture capitalists use to measure success. JJDC has earned their trust by sharing quality deals and by pledging to stick with investments in later financing rounds. Perhaps the most troubling lesson learned by JJDC relates to their ability to attract and retain high-quality venture capitalist talent to work for them. JJDC simply cannot offer the incentives and the equity participation in the venture capital fund that the best venture capitalists Strategy #9; Participate in an "emerging industry fund" (EIF). Large companies like Lucent Technologies, Merck, and DuPont have been investing in start-up ventures for years. The research firm. Venture One Corp., estimates that 27% of all venture capital rounds in 1998 included one or more corporate investors.^" However, the vast majority of these investments are passive—made by the large company's pension fund—and include no systematic mechanisms to insure that the corporate investor gains any strategic insight from its investment. Today, a few far-sighted industry-leading corporations—who are desperate to innovate because they do not know how their industries will evolve—are contributing capital to a specially created venture capital fund and setting up knowledge transfer processes to learn how radical innovations are being commercialized. A Fortune 500 food company and major U.S. pharmaceutical company, for example, have recently joined forces to invest in the emerging health and wellness industry. Adobe and Texas Instruments have established fuftds that are managed by H&Q Venture Associates. These companies invest in, but do not control, the operations of the fund. In its pure form, the majority of EIF capital comes from institutional investors who are seeking above average financial returns and believe that the fund's unique structure provides them with a lower risk way to accomplish this objective. The EIF often invests in companies in need of growth capital, not early stage start-ups. This eliminates much of the controversy and risk involved with radical innovations and allows the EIF's corporate investors to more quickly "see" the commercial potential of the new ideas. As an executive from the pharmaceutical company observes: "the primary risk is market development, not technology or science."^' The EIF is managed by independent venture capitalists (VCs). This feature, along with the inclusion of-institutional capital, distinguishes the EIF from other corporate venturing initiatives and dramatically changes both its nature and purpose. Unlike the typical corporate venture or corporate sponsored venture fund, EIF corporate partners are not playing with just their own money, and the VCs are not part of the corporate family. Without the leverage of third-party capital and the skills, greed, and discipline of the independent venture capitalist, the fund will be constrained by the same factors that limit captive corporate venture funds. CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 83 How To Manage Radical Innovation F I G U R E I . Strategies for Stimulating Radical Innovation in Large Companies Control over Innovation and Commercialization Strategy Process Likely Motivational Impact on the Radical Innovators Availability of Economic and Emotional Support 1. Talk about Innovation Complete Lovi' Unpredictable 2. Hire More nnovators 100%—As Long as They Stay Low Mixed 3, Infomnal Project Laboratories 100%—At Least in the Beginning Moderate Low 4. Idea Markets Moderate to High Moderate—It Depends on the Degree of Autonomy Could Be High, If Properly Structured 5. Dual Strategies High Mixed—It Depends on the Complexity of the Organization Moderate to High 6. Acquisitions and Alliances Moderate to High Moderate—It Depends on the Degree of Alliance Integration Will Depend Entirely on the Deal 7. Corporate Venturing High—At Least in the Beginning Moderate to High—^The More "Hands Off" the Better Limited—Depends on the Budget 8. Corporate Venture Funds Moderate—Often a Contentious Issue High—^As Long as the Fund Moderate to High is Very "Hands Off" 9. Emerging Industry Fund (EIF) Low—It Is Indirect Very High Potentially Very High, Depending on Arrangements with Corporate Investor and VC Manager If the EIF structure prohibits the innovation-starved corporate investor from exercising control over the entrepreneurs, what is in it for the large corporation? Why participate in an EIF? The answer is certainly not hard to understand—they want to make above average investment returns. However, when it comes to stimulating radical innovation, what advantages does this strategy have over the eight others? (See Figure 1 for a comparison of the important characteristics of all nine of the innovation-stimulating strategies.) The secret of success for an EIF is the quality of the independent VC firm that manages the fund. Not only must the VCs invest wisely, they must orchestrate a network of relationships that accomplishes the objectives of the fund's investors. All investors want to maximize their economic returns. However, the EIF makes greater strategic 84 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation F I G U R E I . Strategies for Stimulating Radical Innovation in Large Companies (continued) Strategy Innovator's Perception of the Quality of this Support Opportunity to Learn about the Full Potential of the Innovation Degree of Difficulty of this Learning 1. Talk about Innovation Low Low—Only One Way Very Easy 2. Hire More Innovators Low Probably Low—Depends on the Courage of the Hired Innovators Easy 3. Infomnal Project Laboratories Low Low t o Moderate Easy, If Ideas Are Incremental 4. Idea Markets Low, but Depends on the Innovator's Political Savvy Moderate, IfThere Is a "Hands OfT" Policy Easier with Incremental Innovation 5. Dual Strategies High, If Conflicts Are Well Managed Mixed—Very Hard t o Stray Too Far From the Core Technology Somewhat Difficult Due t o Conflicts 6. Acquisitions and Alliances Mixed—Will Depend on How Connplementary the Innovation is High—Unless the Innovator-Partner in Pushed in One Direction Mixed—^The Question is W h o Learns What? 7. CorporateVenturing Mixed—Comes with "Strings" Attached Moderate—^Very Hard t o Keep from Meddling Easy 8. Corporate Venture Funds Can Be High, If the Corporation's Motives Aren't Questioned High, If Innovators are Civen Freedom Often Quite Difficult— Often Depends on Expectations 9. Emerging Industry Fund (EIF) High—Will Depend on the Quality of theVCs High—If Learning Goals Are Clear and Proper Mechanisms Are in Place Difficult—It Takes Patience and Discipline sense for the innovation-seeking corporate investors when they participate in a robust knowledge transfer process that allows them to learn about the commercial feasibility of the radically new ideas being developed by the fund's portfolio companies. The learning process is three-dimensional and is "behind the scenes," with none of the mechanisms impeding the fund's primary objective of generating high economic returns. In fact, the multi-dimensional knowledge transfer process significantly enhances the EIF's ability to generate above average returns. The more the VCs know about the emerging industry and how tbe new markets differ from old ones, the "smarter" their money will be. The more the entrepreneurs in tbe portfolio companies know about the independent VCs business management practices and the corporate lead limited partners' market- CAUFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 85 How To Manage Radical Innovation ing, sales, or distribution practices, tbe faster they will be able to grow their companies. The more the large corporate investors know about tbe potential of tbe radical innovations, the higher tbe value tbat will be placed on each of the successful portfolio companies. Even tbe less successful ones will be worth more because of tbe active, focused, and informed VC support they received being part of the EIF portfolio. Researcb by Walter Powell at the University of Arizona and Rob Cross and Lloyd Baird at Boston University sheds ligbt on bow this knowledge transfer process works and bow it stimulates innovation in large companies. Powell studied the field of biotechnology and concluded that companies that have active collaborative networks, including involvement with new ventures and emerging companies trying to commercialize radical innovation, are exposed to more new ideas and are potentially more innovative. Tbe key to being more innovative turns out to be tbe company's ability to absorb knowledge, not the availability of radically new ideas.^* Cross and Baird found that knowledge transfer depended more on personal interactions than on technology or data bases.^^ Building on these insights, corporate participants in an EIF can use seven knowledge transfer mechanisms to enhance their appreciation of the potential value of the radical innovations they indirectly invest in: • Place an Executive in the Office of the VC. This keeps the corporate participants fully informed of the fund's deal flow and tbe commercialization activities of its portfolio companies. The on-site executive also belps the portfolio companies access the resources of the large corporate investors. • Designate an EIF Network Manager. Tbe Network Manager, located at corporate headquarters, is at the receiving end of the knowledge flow from the EIF. He or she is responsible for enhancing and sustaining tbe dialogue between the corporation and the R&D professionals, the marketers, the operators, and the executives of all the companies associated with the fund. • Create Absorption Teams within the Corporation That Wants to Learn. Tbe goal is to ensure tbat new ideas are spread around the corporate partner's organization by turning individual expertise and insight into organizational learning. Identify small teams of people who will be responsible for learning about the experiences of each portfolio company, with different people assigned to each venture in order to assure rapid and diffuse absorption of tbe new knowledge. • Set Up an Idea Library. Eacb corporate participant sbould establish a central repository for tbe documentable knowledge tbat emerges from the EIF activities and investments. Tbe library would include working papers, due diligence reports, memos, presentations made by various experts, legal documents, and the minutes of the fund's Advisory Board. 86 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW V O L 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 H o w To Manage Radical Innovation • Create an EIF Web Site. To encourage scientific dialogue, all tbe portfolio companies, tbe corporate partners and the VCs sbould have secure access to tbe EIF's own web site. • Establish Formal Forums to Compare Notes. In forums bosted periodically by each corporate participant, representatives of tbe fund's portfolio companies and its Advisory Board focus on specific tecbnologies, ideas, or issues. Participants can present issues, ideas, successes, failures, and insigbts and can explore ways to capitalize on their pooled experience. • Respond to Requests for Informal Exchanges. Perbaps tbe most important knowledge transfer mechanism is the informal conversations and exchanges between tbe corporate limited partners and tbe individual portfolio companies. Tbese include cross-functional and multi-functional problem-solving meetings aimed at helping a specific entrepreneur commercialize his or ber innovation. Strategy #9 is too arm's-lengtb, too expensive, and too risky to be relied upon as tbe sole source of commercially viable radical innovations. However, when combined with one or more of the otber strategies, it may provide multiple windows tbrougb which a company can view tbe future evolution of an emerging industry. Moreover, it gives the large corporation informed strategic options it would otberwise not have. Think Ahead what is tbe likelihood tbat tbe leaders of major U.S. industries will grow by virtue of homegrown breakthrough innovations? Will companies like GM, Philip Morris, and Exxon lead tbe way in defining and then meeting the needs of tomorrow's consumers? Is it not more likely that small, emerging companies will discover and exploit tbe best new ideas? If companies like J&J, Intel, and Cisco Systems continue to generate a constant stream of innovations, migbt it be because tbey bave adopted truly unconventional approacbes to tbe innovation management process? During times of disruptive change, just wben tbe need for new initiatives and radical tbinking is tbe greatest, most industry leaders engage in more market researcb on tbe value propositions of existing customer segments. Tbey bire more consultants who explore ways to expand and sustain tbe company's current sources of competitive advantage; and they fund more detailed and comprehensive analyses of the banks of data in tbe company's arcbives. These responses to tbe need for greater innovation are all part of tbe genetic code of tbe typical big company. In tbe new millennium, tbe leaders of traditional industries are going to bave to apply new innovation management strategies if tbey are to maintain tbeir leadersbip positions. CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW V O L 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000 87 Hov\/To Manage Radical Innovation Notes 1. Curt Wang, "Seven Ways Brand Management Kills Innovation," Food Processing (September 1999), pp. 35-40. 2. CorpTech database, owned by Corporate Technology Information Services, Inc., see Hanson, Stein, and Moore (1984). 3. Samuel Kortum and Josh Lerner, "Does Venture Capital Spur Innovation?" National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, Cambridge, MA, 1998. 4. "Stall Points," Research Report of the Corporate Strategy Board, 1998. 5. Clayton Christensen, The Innovator's Dilemma (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1997). 6. "Getting to 'Eureka'!" Business Week, November 10, 1997, p. 76. 7. David McClelland, Human Motivation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986). 8. George Litwin and Robert Stringer, Motivation and Organizational Climate (Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968). 9. Brian O'Reilly, "What it Takes to Start a Startup," Fortune, June 7, 1999. 10. Ibid., p. 135 11. Comment in a personal interview with the author. 12. Michael Tushman and Charles O'Reilly, Winning Through Innovation (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1997), p. 171. 13. Ibid., p. 171. 14. Ibid., p. 173. 15. For ideas and a discussion of how to squeeze the most out of business alliances and partnerships, see Jordan Lewis, Partnerships for Profit (New York, NY: The Free Press, 1990); Kathryn Harrigan, Managing for Joint Venture Success (New York, NY: Lexington Books, 1986). 16. Peter Cohan, The Technology Leaders (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1997), pp. 79-81. 17. Zenas Block and Ian MacMillan, Corporate Venturing (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1993), pp. 196-228. 18. Ibid., p. 196. 19. Comment in a personal interview with the author. 20. Thomas Helimann and Manju Puri, "The Interaction between Product Market and Financing Strategy: The Role of Venture Capital," Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper No. 1561, May 1999. 21. Business Week, October 11, 1999, p. 28. 22. Block and MacMillan, op. cit., p. 343. 23. Private correspondence with the author. 24. Luisa KroU, "Entrepreneurs Big Brothers," Forbes, May 3, 1999. 25. Comment in personal interview with the author. 26. Walter Powell, "Learning from Collaboration: Knowledge and Networks in the Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Industries," California Management Review, 40/3 (Spring 1998): 228-240. 27. Rob Cross and Lloyd Baird, "Technology is Not Enough: Improving Performance by Building Organizational Memory," Sloan Management Review, 41/3 (Spring 2000): 69-78. CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL 42, NO. 4 SUMMER 2000

© Copyright 2026