IB History of the Americas Skills Handbook

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

1

IB History of the Americas

Skills Handbook

I) How to read history…………………………………………………………...........................1

II) How to take notes ………………………………………………………….............................4

III) Document analysis/OPVL…………………………………………………………………....7

IV) Writing for IB History……………………………………………………………………....11

V) Internal Assessment-Historical Investigation……………………………………………….19

VI) PowerPoints and Roundtables……………………………………………………………....22

VII) Evaluating Websites……………………………………………………………………..….23

Appendix………………………………………………………………………………………....25

A: PowerPoint Rubric…………………………………………………………………...25

B: PowerPoint Rubric…………………………………………………………………...26

C: Essay Markbands…………………………………………………………………….27

D: IA Historical Investigation Rubric…………………………………………………...29

E: IA Historical Investigation FAQ……………………………………………………..31

F: Glossary of Command Terms

I) How to Read History (and learn stuff)

You are expected to do much more reading IB, so you might as well learn to read more

effectively. Here are five tips to help you improve your reading:

1. Read for a purpose (Styles of reading) There are three styles of reading which we use in

different situations: scanning, skimming, and detailed

Scanning: for a specific focus. The technique you use when you’re looking up a name in the

phone book: you move your eye quickly over the page to find particular words or phrases

that are relevant to the task you’re doing. It’s useful to scan parts of texts to see if they’re

going to be useful to you:

•

•

•

the introduction or preface of a book

the first or last paragraphs of chapters

the concluding chapter of a book.

Skimming: for getting the gist of something The technique you use when you’re going

through a newspaper or magazine: you read quickly to get the main points, and skip over the

detail. It’s useful to skim:

•

•

•

to preview a passage before you read it in detail

to refresh your understand of a passage after you’ve read it in detail.

to decide if a book in the library is useful for your research.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

2

Detailed reading: for extracting information accurately Where you read every word, and

work to learn from the text.

•

•

In this careful reading, you may find it helpful to skim first, to get a general idea, but

then go back to read in detail.

Use a dictionary to make sure you understand all the words used.

2. Active reading

When you’re reading for your course, you need to make sure you’re actively involved with the

text. It’s a waste of your time to just passively read, the way you’d read a thriller on holiday.

Always take notes (two column notes or outline) to keep up your concentration and

understanding.

Here are four tips for active reading.

Underlining and highlighting

>Pick out what you think are the most important parts of what you are reading.

>If you are a visual learner, you’ll find it helpful to use different colors to highlight

different aspects of what you’re reading. (ex. pink for social, green for economic, …)

Note key words, terminology, names, places and dates

>Record the main headings and outline as you read. This is really easy in a textbook,

because the headings are already printed in bold type.

>Use one or two keywords for each point.

>When you cannot mark the text, keep a folder of notes you make while reading.

>Leave space in your notes to add information discussed in class

Questions

>Before you start reading something like an article, a chapter or a whole book, prepare

for your reading by noting questions you want the material to answer.

>In a text book change the headings to a question. (ex. Causes of the Great Depression. =

What caused the Great Depression?)

>While you’re reading, note questions which the author raises.

>In IB it is important to note alternative points of view

Summaries

Pause after you’ve read a section of text. Then:

1. put what you’ve read into your own words;

2. skim through the text and check how accurate your summary is and

3. fill in any gaps.

A tip for speeding up your active reading

You should learn a huge amount from reading on your own and not by being spoon fed

by a teacher. If you read passively, without learning, you’re wasting your time. So train

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

3

your mind to learn.

Try the SQ3R technique. SQ3R stands for Survey, Question, Read, Recall and Review.

Survey

Gather the information you need to focus on the work and set goals:

•

•

•

•

•

Read the title to help prepare for the subject

Read the introduction or summary to see what the author thinks are the key points

Notice the boldface headings to see what the structure is

Notice any maps, graphs or charts. They are there for a purpose

Notice the reading aids, italics, bold face, questions at the end of the chapter.

They are all there to help you understand and remember.

Question

Help your mind to engage and concentrate. Your mind is engaged in learning when it is

actively looking for answers to questions. Try turning the boldface headings into

questions you think the section should answer.

Read

Read the first section with your questions in mind. Look for the answers, and make up

new questions if necessary.

Recall

After each section, stop and think back to your questions. See if you can answer them

from memory. If not, take a look back at the text. Do this as often as you need to.

Review

Once you have finished the whole chapter, go back over all the questions from all the

headings. See you if can still answer them. If not, look back and refresh your memory.

4. Spotting authors’ navigation aids

Learn to recognize sequence signals, for example:

“Three advantages of…” or “A number of methods are available…” leads you to expect several

points to follow.

The first sentence of a paragraph will often indicate a sequence: “One important cause of…”

followed by “Another important factor…” and so on, until “The final cause of…”

Whatever you are reading, be aware of the author’s background. It is important to recognize the

bias given to writing by a writer’s political, religious, social background. Learn which

newspapers and journals represent a particular standpoint.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

4

5. Words and vocabulary

In your writing for IB, you are expected to use the correct vocabulary in the context of your

analytical writing. On quizzes you are expected to define a term like “containment”. In an essay

you would be asked to evaluate Truman’s policy of containment. To expand your vocabulary:

Choose a large dictionary rather than one which is ‘compact’ or ‘concise’. You want one which

is big enough to define words clearly and helpfully (around 1,500 pages is a good size).

Avoid dictionaries which send you round in circles by just giving synonyms. A pocket dictionary

might suggest: ‘impetuous = rash’.

A more comprehensive dictionary will tell you that impetuous means ‘rushing with force and

violence’, while another gives ‘liable to act without consideration’, and add to your

understanding by giving the derivation ‘14th century, from late Latin impetuous = violent’.

It will tell you that rash means ‘acting without due consideration or thought’, and is derived from

Old High German rasc = hurried.

So underlying these two similar words is the difference between violence and hurrying.

There are over 600,000 words in the Oxford English Dictionary; most of them have different

meanings, (only a small proportion are synonyms).

If you haven’t got your dictionary with you, note down words which you don’t understand and

look them up later. It is a waste of time to read an essay on neorealism in foreign policy without

first being able to define neorealism.

Source: http://www.studyskills.soton.ac.uk/studytips/reading_skills.htm

II) How to Take Notes (and learn stuff)

To succeed (learn stuff and make good marks) you will have to do a lot of note-taking at,

much more than you have ever had to do before.

We cover six aspects of making notes:

a. Be selective

b. Mind maps

c. Cornell system

d. Using notes

e. Taking notes as you listen

a. Be selective

Note-taking does not mean writing down everything you read or hear. Your notes should be a

clear summary of essential points in a text or lecture. Be selective about what you write

down. Notes should help you to:

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

•

•

5

Fix information in your mind, and

Revise.

Here are two ways of taking notes. Which do you prefer?

b. Mind-mapping

If you're a Visual Learner you'll find patterns easier to use than lists of ideas, so you may

want to use mind maps (which are also called spider diagrams).

Mind maps can help you to connect information in a variety of ways. You can use them for:

•

•

•

Making notes,

Planning essay answers and

Revising.

Start in the middle of a page with the subject title or topic, and add major points along a line

from the centre, with additional ideas branching out from the main points. Use connecting

lines to link up ideas/points from different branches. Like this:

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

6

c. Cornell Method

If you are an Auditory Learner, you may prefer to use a system like the Cornell Method,

an example of which is given below:

e. Using your notes

Whatever method you use, it's important that you do something with your notes. You

need to go through them while the lecture is still fresh in our mind, within 24 hours, and

make sure you tidy them up and summarize them.

Use highlighters and coloured pens to highlight key points and to link relevant facts and

ideas.

Make it a rule after each lecture to:

•

•

Tidy up your notes

Make them more legible if you need to

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

7

Summarize your notes

Write down the main points to make it easy to revise for exams later.

If you use the Cornell system, you can overlay your pages so you only see the left-hand

margin, and read the essentials of the lecture from your summary notes.)

Fill in your notes

Fill in from memory examples and facts which you didn't have time to get down in the

lecture

Clarify your notes

If any parts of the lecture were unclear, ask me, a reliable fellow-student, or check your

books

Highlight your notes

Make the key points stand out:

•

•

•

Underline them,

Highlight them in a bright color, or

Mark them with asterisks.

f. Making notes as you listen

>Apart from the date and title (if it's given) don't try to write anything at the start of a

lecture.

>Listen to find out what the content is going to be.

>Write down key words / ideas. You don't have to write in complete sentences.

>Use abbreviations.

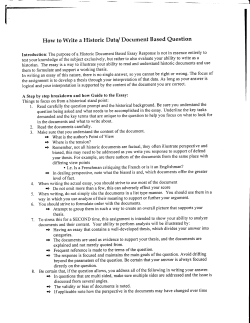

III) How to Analyze Documents (and learn stuff)

History is all about the documents! Being able to analyze documents following the OPVL

guidelines is crucial for success in IB history

OPVL

Origin, Purpose, Value and Limitation (OPVL) is a technique for analyzing historical

documents. It is used extensively in the International Baccalaureate curriculum and testing

materials, and is incredibly helpful in teaching students to be critical observers. It is also known

as Document Based Questions (DBQ).

Origin:

In order to analyze a source, you must first know what it is. Sometimes not all of these questions

can be answered. The more you do know about where a document is coming from, the easier it

is to ascertain purpose, value and limitation. The definition of primary and secondary source

materials can be problematic. There is constant debate among academic circles on how to

definitively categorize certain documents and there is no clear rule of what makes a document a

primary or a secondary source.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

•

•

8

Primary – letter, journal, interview, speeches, photos, paintings, etc. Primary sources are

created by someone who is the “first person”; these documents can also be called

“original source documents. The author or creator is presenting original materials as a

result of discovery or to share new information or opinions. Primary documents have not

been filtered through interpretation or evaluation by others. In order to get a complete

picture of an event or era, it is necessary to consult multiple--and often contradictory-sources.

Secondary – materials that are written with the benefit of hindsight and materials that

filter primary sources through interpretation or evaluation. Books commenting on a

historical incident in history are secondary sources. Political cartoons can be tricky

because they can be considered either primary or secondary. Note: One is not more

reliable than the other. Valuable information can be gleaned from both types of

documents. A primary document can tell you about the original author’s perspective; a

secondary document can tell you how the primary document was received during a

specific time period or by a specific audience.

Other questions must be answered beyond whether the source is primary or secondary and will

give you much more information about the document that will help you answer questions in the

other categories.

• Who created it?

• Who is the author?

• When was it created?

• When was it published?

• Where was it published?

• Who is publishing it?

• Is there anything we know about the author that is pertinent to our evaluation?

This last question is especially important. The more you know about the author of a document,

the easier it is to answer the following questions. Knowing that George was the author of a

document might mean a lot more if you know you are talking about George Washington and

know that he was the first president, active in the creation of the United States, a General, etc.

Purpose:

This is the point where you start the real evaluation of the piece and try to figure out the purpose

for its creation. You must be able to think as the author of the document. At this point you are

still only focusing on the single piece of work you are evaluating.

• Why does this document exist?

• Why did the author create this piece of work? What is the intent?

• Why did the author choose this particular format?

• Who is the intended audience? Who was the author thinking would receive this?

• What does the document “say”?

• Can it tell you more than is on the surface?

Avoid saying “I think the document means this…” Obviously, if you are making a statement it is

coming from your thoughts. Instead say: “The document means this…because it is supported by

x evidence.”

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

9

Value:

Now comes the hard part. Putting on your historian hat, you must determine: Based on who

wrote it, when/where it came from and why it was created…what value does this document have

as a piece of evidence? This is where you show your expertise and put the piece in context.

Bring in your outside information here.

• What can we tell about the author from the piece?

• What can we tell about the time period from the piece?

• Under what circumstances was the piece created and how does the piece reflect those

circumstances?

• What can we tell about any controversies from the piece?

• Does the author represent a particular ‘side’ of a controversy or event?

• What can we tell about the author’s perspectives from the piece?

• What was going on in history at the time the piece was created and how does this piece

accurately reflect it? It helps if you know the context of the document and can explain what the

document helps you to understand about the context.

The following is an example of value analysis:

The journal entry was written by President Truman prior to the dropping of the atomic bomb on

Japan and demonstrates the moral dilemma he was having in making the decision of whether to

drop the bomb or not. It shows that he was highly conflicted about the decision and very aware

of the potential consequences both for diplomatic/military relations and for the health and

welfare of the Japanese citizens.

Limitation:

This is probably the hardest part. The task here is not to point out weaknesses of the source, but

rather to say: at what point does this source cease to be of value to us as historians? With a

primary source document, having an incomplete picture of the whole is a given because the

source was created by one person (or a small group of people?), naturally they will not have

given every detail of the context. Do not say that the author left out information unless you have

concrete proof (from another source) that they chose to leave information out. Also, it is obvious

that the author did not have prior knowledge of events that came after the creation of the

document. Do not state that the document “does not explain X” (if X happened later).

Being biased does not limit the value of a source! If you are going to comment on the bias of a

document, you must go into detail. Who is it biased towards? Who is it biased against? What

part of a story does it leave out? What part of the story is MISSING because of parts left out?

• What part of the story can we NOT tell from this document?

• How could we verify the content of the piece?

• Does this piece inaccurately reflect anything about the time period?

• What does the author leave out and why does he/she leave it out (if you know)?

• What is purposely not addressed?

This is again an area for you to show your expertise of the context. You need to briefly explain

the parts of the story that the document leaves out. Give examples of other documents that might

mirror or answer this document. What parts of the story/context can this document not tell?

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

10

An OPVL paragraph would follow the example below:

The origin of this source is a journal that was written by _________ in ________ in _______. Its

purpose was to __________________ so ___________________. A value of this is that it gives

the perspective of __________________________. However, a limitation is that ____________

______________________, making_____________________ ___________________________.

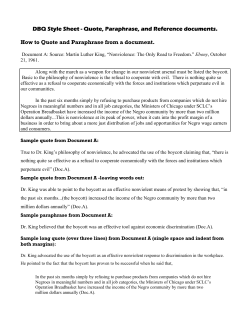

Cartoon Analysis

Author of the cartoon:

Date of publication:

Newspaper or medium:

Level 1

Visuals

Words (not all cartoons include words)

1. List the objects or people you see in the

1. Identify the cartoon caption and/or title.

cartoon.

2. Locate three words or phrases used by

the cartoonist to identify objects or

people within the cartoon.

3. Record any important dates or numbers

that appear in the cartoon.

Level 2

Visuals

Words

2. Which of the objects on your list are

4. Which words or phrases in the cartoon

symbols?

appear to be the most significant? Why

3. What do you think each symbol means?

do you think so?

5. List adjectives that describe the

emotions portrayed in the cartoon.

Level 3

A. Describe the action taking place in the cartoon.

B. Explain how the words in the cartoon clarify the symbols.

C. Explain the message of the cartoon.

D. What special interest groups would agree/disagree with the cartoon's message? Why?

National Archives and Records Administration Document Analysis Forms

< http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/ >

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

11

IV) Writing in Social Studies

Tips for Writing Your Thesis Statement

1.Determine what kind of paper you are writing:

•

•

•

An analytical paper breaks down an issue or an idea into its component parts, evaluates

the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

An expository (explanatory) paper explains something to the audience.

An argumentative paper makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with

specific evidence. The claim could be an opinion, a policy proposal, an evaluation, a

cause-and-effect statement, or an interpretation. The goal of the argumentative paper is to

convince the audience that the claim is true based on the evidence provided.

If you are writing a text which does not fall under these three categories (ex. a narrative), a thesis

statement somewhere in the first paragraph could still be helpful to your reader.

2. Your thesis statement should be specific—it should cover only what you will discuss in your

paper and should be supported with specific evidence.

3. The thesis statement usually appears at the end of the first paragraph of a paper.

4. Your topic may change as you write, so you may need to revise your thesis statement to reflect

exactly what you have discussed in the paper.

Thesis Statement Examples

Example of an analytical thesis statement:

An analysis of the college admission process reveals one challenge facing counselors: accepting

students with high test scores or students with strong extracurricular backgrounds.

The paper that follows should:

•

•

explain the analysis of the college admission process

explain the challenge facing admissions counselors

Example of an expository (explanatory) thesis statement:

The life of the typical college student is characterized by time spent studying, attending class,

and socializing with peers.

The paper that follows should:

•

explain how students spend their time studying, attending class, and socializing with

peers

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

12

Example of an argumentative thesis statement:

High school graduates should be required to take a year off to pursue community service projects

before entering college in order to increase their maturity and global awareness.

The paper that follows should:

•

present an argument and give evidence to support the claim that students should pursue

community projects before entering college

Structure of an Essay

1) Introduction

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions:

1. What is this?

2. Why am I reading it?

3. What do you want me to do?

You should answer these questions by doing the following:

1. Set the context – provide general information about the main idea, explaining the

situation so the reader can make sense of the topic and the claims you make and support

2. State why the main idea is important – tell the reader why s/he should care and keep

reading. Your goal is to create a compelling, clear, and convincing essay people will want

to read and act upon

3. State your thesis/claim – compose a sentence or two stating the position you will support

with logos (sound reasoning: induction, deduction), pathos (balanced emotional appeal),

and ethos (author credibility).

For exploratory essays, your primary research question would replace your thesis statement so

the audience understands why you began your inquiry. An overview of the types of sources you

explored might follow your research question.

If your argument paper is long, you may want to forecast how you will support your thesis by

outlining the structure of your paper, the sources you will consider, and the opposition to your

position. Your forecast could read something like this:

First, I will define key terms for my argument, and then I will provide some background of the

situation. Next I will outline the important positions of the argument and explain why I support

one of these positions. Lastly, I will consider opposing positions and discuss why these positions

are outdated. I will conclude with some ideas for taking action and possible directions for future

research.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

13

This is a very general example, but by adding some details on your specific topic, this forecast

will effectively outline the structure of your paper so your readers can more easily follow your

ideas.

Thesis Checklist

Your thesis is more than a general statement about your main idea. It needs to establish a clear

position you will support with balanced proofs (logos, pathos, ethos). Use the checklist below to

help you create a thesis.

This section is adapted from Writing with a Thesis: A Rhetoric Reader by David Skwire and

Sarah Skwire:

Make sure you avoid the following when creating your thesis:

•

•

•

•

•

A thesis is not a title: Homes and schools (title) vs. Parents ought to participate more in

the education of their children (good thesis).

A thesis is not an announcement of the subject: My subject is the incompetence of the

Supreme Court vs. The Supreme Court made a mistake when it ruled in favor of George

W. Bush in the 2000 election.

A thesis is not a statement of absolute fact: Jane Austen is the author of Pride and

Prejudice.

A thesis is not the whole essay: A thesis is your main idea/claim/refutation/problemsolution expressed in a single sentence or a combination of sentences.

Please note that according to the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, Sixth

Edition, "A thesis statement is a single sentence that formulates both your topic and your

point of view" (Gibaldi 56). However, if your paper is more complex and requires a

thesis statement, your thesis may require a combination of sentences.

Make sure you follow these guidelines when creating your thesis:

•

•

•

A good thesis is unified: Detective stories are not a high form of literature, but people

have always been fascinated by them, and many fine writers have experimented with

them (floppy). vs. Detective stories appeal to the basic human desire for thrills (concise).

A good thesis is specific: The Great Depression was a major economic crisis in the

United States. vs. The Great Depression changed the role of the federal government with

regard to economic management in the United States

Try to be as specific as possible (without providing too much detail) when creating your

thesis

Quick Checklist:

_____ The thesis/claim follows the guidelines outlined above

_____ The thesis/claim matches the requirements and goals of the assignment

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

_____ The thesis/claim is clear and easily recognizable

_____ The thesis/claim seems supportable by good reasoning/data, emotional appeal

2-3,4) Body Paragraphs: Moving from General to Specific Information

Your paper should be organized in a manner that moves from general to specific information.

Every time you begin a new subject, think of an inverted pyramid - the broadest range of

information sits at the top, and as the paragraph or paper progresses, the author becomes more

and more focused on the argument ending with specific, detailed evidence supporting a claim.

Lastly, the author explains how and why the information she has just provided connects to and

supports her thesis (a brief wrap up or warrant).

Image Caption: Moving from General to Specific Information

The four elements of a good paragraph (TTEB)

A good paragraph should contain at least the following four elements: Transition, Topic

sentence, specific Evidence and analysis, and a Brief wrap-up sentence (also known as a

warrant) – TTEB!

1. A Transition sentence leading in from a previous paragraph to assure smooth reading.

This acts as a hand off from one idea to the next. (end of previous paragraph)

2. A Topic sentence that tells the reader what you will be discussing in the paragraph.

3. Specific Evidence and analysis that supports one of your claims and that provides a

deeper level of detail than your topic sentence.

14

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

15

4. A Brief wrap-up sentence that tells the reader how and why this information supports the

paper’s thesis. The brief wrap-up is also known as the warrant. The warrant is important

to your argument because it connects your reasoning and support to your thesis, and it

shows that the information in the paragraph is related to your thesis and helps defend it.

Supporting evidence (induction and deduction)

Induction

Induction is the type of reasoning that moves from specific facts to a general conclusion.

When you use induction in your paper, you will state your thesis (which is actually the

conclusion you have come to after looking at all the facts) and then support your thesis

with the facts. The following is an example of induction taken from Dorothy U. Seyler’s

Understanding Argument:

Facts:

There is the dead body of Smith. Smith was shot in his bedroom between the hours of

11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m., according to the coroner. Smith was shot with a .32 caliber

pistol. The pistol left in the bedroom contains Jones’s fingerprints. Jones was seen, by a

neighbor, entering the Smith home at around 11:00 p.m. the night of Smith’s death. A

coworker heard Smith and Jones arguing in Smith’s office the morning of the day Smith

died.

Conclusion: Jones killed Smith.

Here, then, is the example in bullet form:

•

•

•

Conclusion: Jones killed Smith

Support: Smith was shot by Jones’ gun, Jones was seen entering the scene of the

crime, Jones and Smith argued earlier in the day Smith died.

Assumption: The facts are representative, not isolated incidents, and thus reveal a

trend, justifying the conclusion drawn.

Deduction

When you use deduction in an argument, you begin with general premises and move to a

specific conclusion. There is a precise pattern you must use when you reason deductively.

This pattern is called syllogistic reasoning (the syllogism). Syllogistic reasoning

(deduction) is organized in three steps:

1. Major premise

2. Minor premise

3. Conclusion

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

16

In order for the syllogism (deduction) to work, you must accept that the relationship of

the two premises lead, logically, to the conclusion. Here are two examples of deduction

or syllogistic reasoning:

Socrates

1. Major premise: All men are mortal.

2. Minor premise: Socrates is a man.

3. Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

Lincoln

1. Major premise: People who perform with courage and clear purpose in a crisis are

great leaders.

2. Minor premise: Lincoln was a person who performed with courage and a clear

purpose in a crisis.

3. Conclusion: Lincoln was a great leader.

So in order for deduction to work in the example involving Socrates, you must agree that

1) all men are mortal (they all die); and 2) Socrates is a man. If you disagree with either

of these premises, the conclusion is invalid. The example using Socrates isn’t so difficult

to validate. But when you move into more murky water (when you use terms such as

courage, clear purpose, and great), the connections get tenuous.

For example, some historians might argue that Lincoln didn’t really shine until a few

years into the Civil War, after many Union losses to Southern leaders such as Robert E.

Lee.

The following is a more clear example of deduction gone awry:

1. Major premise: All dogs make good pets.

2. Minor premise: Doogle is a dog.

3. Conclusion: Doogle will make a good pet.

If you don’t agree that all dogs make good pets, then the conclusion that Doogle will

make a good pet is invalid.

Enthymemes

When a premise in a syllogism is missing, the syllogism becomes an enthymeme.

Enthymemes can be very effective in argument, but they can also be unethical and lead to

invalid conclusions. Authors often use enthymemes to persuade audiences. The following

is an example of an enthymeme:

If you have a plasma TV, you are not poor.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

17

The first part of the enthymeme (If you have a plasma TV) is the stated premise. The

second part of the statement (you are not poor) is the conclusion. So the unstated premise

is “Only rich people have plasma TVs.” The enthymeme above leads us to an invalid

conclusion (people who own plasma TVs are not poor) because there are plenty of people

who own plasma TVs who are poor. Let’s look at this enthymeme in a syllogistic

structure:

•

•

•

Major premise: People who own plasma TVs are rich (unstated above).

Minor premise: You own a plasma TV.

Conclusion: You are not poor.

To help you understand how induction and deduction can work together to form a solid

argument, you may want to look at the American Declaration of Independence. The first

section of the Declaration contains a series of syllogisms, while the middle section is an

inductive list of examples. The final section brings the first and second sections together

in a compelling conclusion.

4) Rebuttal Sections

In order to present a fair and convincing message, you may need to anticipate, research, and

outline some of the common positions (arguments) that dispute your thesis. If the situation

(purpose) calls for you to do this, you will present and then refute these other positions in the

rebuttal section of your essay.

It is important to consider other positions because in most cases, your primary audience will be

fence-sitters. Fence-sitters are people who have not decided which side of the argument to

support.

People who are on your side of the argument will not need a lot of information to align with your

position. People who are completely against your argument - perhaps for ethical or religious

reasons - will probably never align with your position no matter how much information you

provide. Therefore, the audience you should consider most important are those people who

haven't decided which side of the argument they will support - the fence-sitters.

In many cases, these fence-sitters have not decided which side to align with because they see

value in both positions. Therefore, to not consider opposing positions to your own in a fair

manner may alienate fence-sitters when they see that you are not addressing their concerns or

discussion opposing positions at all.

Organizing your rebuttal section

Following the TTEB method outlined in the Body Paragraph section, forecast all the information

that will follow in the rebuttal section and then move point by point through the other positions

addressing each one as you go. The outline below, adapted from Seyler's Understanding

Argument, is an example of a rebuttal section from a thesis essay.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

18

When you rebut or refute an opposing position, use the following three-part organization:

The opponent’s argument – Usually, you should not assume that your reader has read or

remembered the argument you are refuting. Thus at the beginning of your paragraph, you need to

state, accurately and fairly, the main points of the argument you will refute.

Your position – Next, make clear the nature of your disagreement with the argument or position

you are refuting. Your position might assert, for example, that a writer has not proved his

assertion because he has provided evidence that is outdated, or that the argument is filled with

fallacies.

Your refutation – The specifics of your counterargument will depend upon the nature of your

disagreement. If you challenge the writer’s evidence, then you must present the more recent

evidence. If you challenge assumptions, then you must explain why they do not hold up. If your

position is that the piece is filled with fallacies, then you must present and explain each fallacy.

5) Conclusions

Conclusions wrap up what you have been discussing in your paper. After moving from general to

specific information in the introduction and body paragraphs, your conclusion should begin

pulling back into more general information that restates the main points of your argument.

Conclusions may also call for action or overview future possible research. The following outline

may help you conclude your paper:

In a general way,

•

•

•

•

restate your topic and why it is important,

restate your thesis/claim,

address opposing viewpoints and explain why readers should align with your position,

call for action or overview future research possibilities.

Remember that once you accomplish these tasks, unless otherwise directed by your instructor,

you are finished. Done. Complete. Don't try to bring in new points or end with a whiz bang(!)

conclusion or try to solve world hunger in the final sentence of your conclusion. Simplicity is

best for a clear, convincing message.

The preacher's maxim is one of the most effective formulas to follow for argument papers:

1. Tell what you're going to tell them (introduction).

2. Tell them (body).

3. Tell them what you told them (conclusion)

Source: Purdue Online Writing Lab < http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl >

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

19

V) Internal Assessment-Historical Investigation

•

•

•

See Appendix E for Historical Investigation FAQ

Historical Investigations must be written following the Chicago Manual of Style,

examples of footnotes and bibliography entries can be found at the website below.

o < http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html >

Footnotes

WHY CITATIONS?

• To acknowledge your dependence on another person's ideas or words, and to distinguish clearly

your own work from that of your sources.

• To receive credit for the research you have done on a project, whether or not you directly quote

or borrow from your sources.

• To establish the credibility and authority of your knowledge and ideas.

• To place your own ideas in context, locating your work in the larger intellectual conversation

about your topic.

• To permit your reader to pursue your topic further by reading more about it.

• To permit your reader to check on your use of the source material.

WHY FOOTNOTES? There are various styles of citations. Historians usually make use of the

Chicago Style (see below for samples). We use this style because of:

•

•

quick access (the information is there at the bottom of the page vs. endnotes where you

have to keep flipping to the end)

elaboration (allows you to further develop select points that would take you away from

the main narrative). The MLA style, for example, does not allow for this tangential

discussion.

WHAT NOT TO FOOTNOTE. It is not necessary to footnote what is referred to as "common

knowledge." Succinctly, if you can find it in the World Book Encyclopedia, then it is common

knowledge.

WHAT SHOULD YOU FOOTNOTE. There are five basic rules that apply to all disciplines and

should guide your own citation practice. Even more fundamental, however, is this general rule:

when in doubt whether or not to cite a source, do it. You will certainly never find yourself in

trouble if you acknowledge a source when it is not absolutely necessary; it is always preferable

to err on the side of caution and completeness. Better still, if you are unsure about whether or not

to cite a source, ask your professor or preceptor for guidance before submitting the paper.

1. Direct Quotation. Any verbatim use of the text of a source, no matter how large or small the

quotation, must be clearly acknowledged. Direct quotations must be placed in quotation marks

or, if longer than three lines, clearly indented beyond the regular margin. The quotation must be

accompanied, either within the text or in a footnote, by a precise indication of the source,

identifying the author, title, and page numbers. Even if you use only a short phrase, or even one

key word, you must use quotation marks in order to set off the borrowed language from your

own, and cite the source.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

20

2. Paraphrase. If you restate another person’s thoughts or ideas in your own words, you are

paraphrasing. Paraphrasing does not relieve you of the responsibility to cite your source. You

should never paraphrase in the effort to disguise someone else’s ideas as your own. If another

author’s idea is particularly well put, quote it verbatim and use quotation marks to distinguish his

or her words from your own. Paraphrase your source if you can restate the idea more clearly or

simply, or if you want to place the idea in the flow of your own thoughts. If you paraphrase your

source, you do not need to use quotation marks. However, you still do need to cite the source,

either in your text or a footnote. You may even want to acknowledge your source in your own

text ("Albert Einstein believed that…"). In such cases, you still need a footnote.

3. Summary. Summarizing is a looser form of paraphrasing. Typically, you may not follow your

source as closely, rephrasing the actual sentences, but instead you may condense and rearrange

the ideas in your source. Summarizing the ideas, arguments, or conclusions you find in your

sources is perfectly acceptable; in fact, summary is an important tool of the scholar. Once again,

however, it is vital to acknowledge your source -- perhaps with a footnote at the end of your

paragraph. Taking good notes while doing your research will help you keep straight which ideas

belong to which author, which is especially important if you are reviewing a series of

interpretations or ideas on your subject.

4. Facts, Information, and Data. Often you will want to use facts or information you have found

in your sources to support your own argument. Certainly, if the information can be found

exclusively in the source you use, you must clearly acknowledge that source. For example, if you

use data from a particular scientific experiment conducted and reported by a researcher, you

must cite your source, probably a scientific journal or a Web site. Or if you use a piece of

information discovered by another scholar in the course of his or her own research, you must

acknowledge your source. Or perhaps you may find two conflicting pieces of information in your

reading -- for example, two different estimates of the casualties in a natural catastrophe. Again,

in such cases, be sure to cite your sources.

Information, however, is different from an idea. Whereas you must always acknowledge use of

other people’s ideas (their conclusions or interpretations based on available information), you

may not always have to acknowledge the source of information itself. You do not have to cite a

source for a fact or a piece of information that is generally known and accepted -- for example,

that Woodrow Wilson served as president of both Princeton University and the United States, or

that Avogadro’s number is 6.02 x 1023. Often, however, deciding which information requires

citation and which does not is not so straightforward. Refer to the later section in this booklet,

Not-So-Common Knowledge, for more discussion of this question.

5. Supplementary Information. Occasionally, especially in a longer research paper, you may not

be able to include all of the information or ideas from your research in the body of your own

paper. In such cases, you may want to insert a note offering supplementary information rather

than simply providing basic bibliographic information (author, title, date and place of

publication, and page numbers). In such footnotes or endnotes, you might provide additional data

to bolster your argument, or briefly present a alternative idea that you found in one of your

sources, or even list two of three additional articles on some topic that your reader might find of

interest. Such notes demonstrate the breadth and depth of your research, and permit you to

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

21

include germane, but not essential, information or concepts without interrupting the flow of your

own paper.

In all of these cases, proper citation requires that you indicate the source of any material

immediately after its use in your paper. For direct quotations, the footnote (which may be a

traditional footnote or the author’s name and page number in parenthesis) immediately follows

the closing quotation marks; for a specific piece of information, the footnote should be placed as

close as possible; for a paraphrase or a summary, the footnote may come at the end of the

sentence or paragraph.

Simply listing a source in your bibliography is not adequate acknowledgment for specific use of

that source in your paper.

For international students, it is especially important to review and understand the citation

standards and expectations for institutions of higher learning in the United States.

AUTOMATIC FOOTNOTE INSERTION. Inserting footnotes is quite easy using current

computer software programs. For example, in Microsoft Word you click on the "Insert" link on

the top menu bar and then in the pop-up menu you have "footnote" as a selection and you click

there. Type footnote in your program's help section for specifics. The number automatically

comes up and now you just type in the data following the examples below and the program

automatically inserts it at the bottom of your page.

QUALITY OF RESEARCH. You will be evaluated on the quality of your selected sources. A

batch of websites is not very impressive; traditional books and articles [on the shelves in

libraries] are recommended. Again, DO NOT simply rely on Internet sources. Note that the

minimum number of footnotes does not mean that you need that many different sources; some of

course can be repeated and others used.

FOOTNOTE SAMPLES. There are various ways that your work can be documented/cited and

you probably learned one or more ways of doing this for another class. Historians prefer the

Chicago style and we will utilize that format in this paper assignment. A footnote number

should come at the end of the sentence. Sometimes, you might want to combine several

footnotes together at the end of a paragraph. Please follow these guidelines as you reference

your sources at the bottom of the page:

•

IF A BOOK: author, title, city and publisher, page number. For example:

Ronald T. Takaki, Iron Cages: Race and Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (New

York: Alfred Knopf Publ., 1979): 2.

•

IF AN ARTICLE: author, title, journal title, volume and page number. For example:

Ronald T. Takaki, “Within the ‘Bowels’ of the Republic,” Journal of History Vol XX,

No. 5: 4.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

•

IF AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OR DICTIONARY: Title, edition and term. For example:

Encyclopedia Britannica, 15th ed., s.v. “Evolution.”

•

FOR A WEBSITE: Title of site, website address. For example:

“Thomas Jefferson on Slavery” in Afro-American Almanac,

http://www.toptags.com/aama/voices/commentary/jeff.htm (25 March 2001).

22

Source: http://www.princeton.edu/pr/pub/integrity/pages/citing.html

VI) PowerPoint/Roundtable

Throughout the year you will be required to produce and PowerPoint presentation to augment a

roundtable discussion in which you teach on a specific topic.

PowerPoint Guidelines

• PowerPoints must be at least 10-15 slides, including:

o Title slide

o Topic/thesis slide

o Bibliography slide

• Presentation must include at least 5 high quality images, graphics, maps, etc.

• Presentations must include at least 2 relevant quotes.

• Slides must include footnotes (10 point font)

• Visually appealing, professional quality

o Contrast between background and font

o Easy to read fonts. Headings 32-44 pt, Body 20-26 pt

o Limited animation

o Appropriate sound or music

Roundtable Guidelines

• You are to direct a class discussion of your topic. You are the teacher

o Above all, be knowledgeable on your topic

o Lead discussion (don’t just lecture), encourage questions

o Provide handouts or note outlines

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

23

VII ) Evaluating Websites as Sources

General search engines are not as comprehensive as they may seem. Also, they use mechanical

and commercial means to set and apply their priorities and criteria.

Rather than a search engine, you can use a directory. Directories are searched in the same way as

search engines, and often offer special search features such as classifications and controlled

vocabulary. Most importantly, directories are built by human reviewers of the listed sites.

Though your searches will give you smaller sets of results, you will find few if any sites in your

results that can't meet minimum standards.

Directories

•

•

•

•

INFOMINE. http://infomine.ucr.edu/

Librarians' Internet Index. http://lii.org/

The WWW Virtual Library. Use http://vlib.iue.it/history/index.html to go directly to the

WWW-VL History Central Catalogue site which can be searched, or can be browsed by

topic, country or eras.

A more complete list of directories is available at SUNY Albany Libraries

http://www.internettutorials.net/subject.html . This site also includes tutorials and other

guides to using the Internet.

Four Main Criteria for Evaluating Websites as Sources

•

•

•

•

Useful or Relevant. Does the site present information about your topic, and can the site

tell you something new about your topic?

Timely. Does the site include a date of posting or most recent update? Obviously

whatever happened in the past will not change, but what we know and think about it does

change. Also, recent updates to a site indicate that someone cares about the site, and

absence of a date indicates an unprofessional attitude.

Appropriate. Who appears to be the target audience for the site? Is it a scholarly or

general audience? How does that audience overlap with your own target audience?

Authoritative. Who wrote or takes responsibility for the information on the site? How do

they know what they claim to know? Is contact information available on the site?

o Methodology. Do they cite sources? Do they explain the process for any research

they report? Do they present clear and sound logic in their arguments? Do they

have a bias, and what difference does that bias make?

o Expertise. Do the author or authors present relevant credentials? Do they have

education or experience that is relevant to the topic? Have they written other

materials on the topic?

o Review. Is there a reputable agency supporting the site? University? Association?

Museum? Library? Has the site been included in a directory or in links from other

sites? Has the site been reviewed?

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

24

On Wikipedia and Other Encyclopedic Sources

Wikipedia is a perfectly good source, depending on what you want to use it for. Its main

problem is the uneven editing. Its biggest assets are the lists of references and external links that

appear at the end of most entries.

Wikipedia’s Self-assessment as a source

< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:About#Using_Wikipedia_as_a_research_tool>

Source: Jim Nichols, History Librarian, Penfield Library, SUNY

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

25

Appendix A: Roundtable/PowerPoint Rubric

Name _____________________________________________ Date ____________________

Topic ______________________________________________________________________

Deadline

Excellent

5

(17+)

on time

Good

Average

Below Avg.

4

3

2

(14-16)

(11-13)

(8-10)

not completely ready at deadline

Poor

1

(7-)

1 day late

Handouts

Format

Visual Quality

Images

Sources

Beyond class

sources

textbooks

none

Cited

Content

Introduction

Purpose/Goals

Clearly stated

Not stated

Analysis

Thorough

analysis

No factual

errors

No analysis

Facts

Few factual

error

Significant

errors

Roundtable

Final Score

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

26

Appendix B: Rubric for PowerPoint Presentations

Name__________________________________________Topic _______________________________

CATEGORY

Background

Font Choice/

Formatting

Use of

Graphics

Spelling and

Grammar

Citations

ContentAccuracy

Effectiveness

Presentation

4

Background does

not detract from text

or other graphics.

Choice of

background is

appropriate for

project.

3

Background does not

detract from text or

other graphics.

Choice of background

could have been

better suited for the

project.

2

Background does

not detract from text

or other graphics.

Choice of

background does

not fit project.

1

Background makes

it difficult to see text

or competes with

other graphics on

the page.

Font formats (e.g.,

color, bold, italic)

have been carefully

planned to enhance

readability and

content.

All graphics are

attractive (size and

colors) and support

the theme/content

of the presentation.

Captions/cited

Font formats have

been adequately

planned to enhance

readability.

Font formatting have

been planned to

complement the

content. It may be a

little hard to read.

Font formatting

makes it difficult to

read the material

A few graphics are

not attractive but all

support the

theme/content of the

presentation.

Captions/cited

All graphics are

attractive but a few

do not seem to

support the

theme/content of the

presentation.

Captions or citations

Graphics are

unattractive &

detract from the

content of the

presentation.

No captions or

citations

Presentation has no

misspellings or

grammatical errors.

Presentation has 1-2

misspellings, but no

grammatical errors.

Presentation has 12 grammatical errors

but no misspellings.

Presentation has

more than 2

grammatical and/or

spelling errors.

8

Correctly applied intext citations or

works cited for all

relevant material

6

Includes in-text

citations or works

cited for most of the

relevant material

4

Includes in-text

citations or works

cited

2

Relevant material is

not cited

All content

throughout the

presentation is

accurate. There are

no factual errors

Most of the content is

accurate but there is

one-piece information

that might be

inaccurate.

Content is typically

confusing or

contains more than

several factual

errors.

Project includes all

material needed to

gain a comfortable

understanding of

the topic chosen.

Project includes most

material needed to

gain a comfortable

understanding of the

topic chosen.

The content is

generally accurate,

but one piece of the

information is clearly

flawed or

inaccurate.

Project is missing

more than two key

elements.

Student presented

the material with

confidence.

Student presented

material but could

have been more

confident.

Student had many

difficulties

presenting

materials.

Student was unable

to present material

before the class.

Project is lacking

several key

elements and has

inaccuracies.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

27

Appendix C: IB History of the Americas: Mark Bands for Essays

IB Rating

16 – 20 (7)

Point Rating

Criteria

A: 94-100

Excellent Performance

1. demonstrates critical thinking (conceptual awareness, insight, and

knowledge)

2. logically structured and provides appropriate examples

3. precise use of terminology which is specific to the subject.

4. demonstrates a familiarity with the literature of the subject

5. analyzes and evaluates evidence.

6. synthesizes knowledge and concepts

7. demonstrates and awareness of alternate points of view and subjective

and ideological biases

13 – 15 (6)

B+: 90-93

1.

2.

3.

4.

10 – 12 (5)

B: 84-89

1.

2.

3.

4.

8 – 9 (4)

C+: 80-83

Satisfactory Performance

C: 74-79

1. demonstrates a secure knowledge and understanding of the subject

2. some ability to structure an answer but with insufficient clarity

3. demonstrates and ability to express knowledge and understanding in

terminology specific to the subject

4. some understanding of the way facts and ideas may be related

5. demonstrates and ability to develop ideas and substantiate assertions

6. descriptive in nature

Very Good Performance

demonstrates detailed knowledge and understanding

coherent, logically structured, and well developed

consistent use of appropriate terminology

demonstrates the ability to analyze evaluate and synthesize knowledge

and concepts

5. demonstrates knowledge of relevant research, theories and issues

6. awareness of different perspectives

Good Performance

demonstrates a sound knowledge and understanding of the subject

uses subject-specific terminology

logically structured and coherent but not fully developed

a competent answer with some attempt to integrate knowledge and

concepts

5. presents and develops contrasting points of view

6. more descriptive than evaluative

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

28

6 – 7 (3)

D+: 70-73

1.

2.

3.

4.

Mediocre Performance

demonstrates some knowledge and understanding of the subject

a basic sense of structure that is not sustained throughout the answer

a basic use of terminology appropriate to the subject

some ability to establish links between facts and ideas

4 – 5 (2)

D: 64-69

1.

2.

3.

4.

Poor Performance

demonstrates a limited knowledge and understanding of the subject

some sense of structure

limited use of appropriate terminology

limited ability to establish links between facts and ideas

0 – 3 (1)

F: 0-63

Very Poor Performance

demonstrates very limited knowledge and understanding of the subject

almost no organizational structure

inappropriate or inadequate use of terminology

limited ability to comprehend data or to solve problems

1.

2.

3.

4.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

29

Appendix D: Historical Investigation Rubric

Name______________________________________________________________________

Topic_______________________________________________________________________

Format

• Cover

• Page number

• Word counts

• Font

• Margins

Criterion A: Plan of Investigation

Marks

Comments

0

There is no plan of the investigation or it is inappropriate.

1

The scope and plan of the investigation are generally appropriate but not clearly

focused.

2

The scope and plan of the investigation are entirely appropriate and clearly focused.

Criterion B: Summary of Evidence

Marks

Comments

0

There is no evidence.

1-2

The investigation has been poorly researched and insufficient evidence has been

produced which is not always referenced.

3-4

The investigation has been adequately researched and some supporting evidence has

been produced and referenced.

5

The investigation has been well researched and good supporting evidence has been

produced which is correctly referenced.

Criterion C: Evaluation of Sources

Marks

Comments

0

There is no description or evaluation of sources.

1

Sources are described but there is no reference to their origin, purpose, value and

limitation.

2-3

The evaluation of sources is generally appropriate and adequate but reference to their

origin, purpose, value and limitation, is limited.

4

The evaluation of sources is thorough and there is appropriate reference to their origin,

purpose, value, and limitation.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

Criterion D: Analysis

Marks

Comments

0

There is no analysis.

1-2

There is some attempt at analyzing the evidence and the importance of the

investigation in its historical context.

3-4

There is analysis of both the evidence and the importance of the investigation in its

historical context. Where appropriate, different interpretations are considered.

5

There is critical analysis of the evidence and the importance of the investigation in its

historical context. Where appropriate, different interpretations are analyzed.

Criterion E: Conclusion

Marks

Comments

0

There is no conclusion.

1

The conclusion is not entirely consistent with the evidence presented.

2

The conclusion is clearly stated and consistent with the evidence presented.

Criterion F: Sources and Word Limit

Comments

Marks

0

A list of sources is not included and/or the investigation is not within the word limit.

1

A list of sources is included but it is incomplete, or one standard method of listing

sources is not used consistently. The investigation is within the word limit.

2

A comprehensive list of all sources is included, using one standard method of listing

sources consistently. The investigation is within the word limit.

Total Marks:

30

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

31

Appendix E: History Internal Assessment FAQ

What is an historical investigation?

It is a written account of between 1,500 and 2,000 words, divided into six sections: a plan of the

investigation, a summary of evidence, an evaluation of sources, an analysis, a conclusion, and a

bibliography or list of sources. The investigation must be a written piece and should be the work

of the individual student. Group work is not permitted.

Who needs to produce an historical investigation?

All higher level (HL) and standard level (SL) history students must write an investigation for

internal assessment.

How many words should there be in each section?

This is not prescribed but one suggestion is: A 100–150, B 500–600, C 250–400, D 500–650,

E 150–200. The total number of words in the investigation must be between 1,500 and 2,000.

How many marks is the investigation worth?

It is marked out of 25 for both SL and HL and is worth 25% of the final assessment at SL and

20% at HL.

When do students work on the investigation?

Timing is up to the teacher, but it is advisable to start the investigation at least three months

before the date that samples for the May and November sessions have to be with the moderators.

DHS students will work on a draft of their IA in the second semester of their 11th grade year.

Final drafts will be turned in around September of their 12th grade year.

What can the investigation be about?

The investigation can consider any genuine historical topic regardless of whether or not it is part

of the IB Diploma Programme history syllabus. Teachers should approve all topics.

What should the teacher do?

1. Explain how the internal assessment works. Students should be given a copy of the

instructions for the historical investigation from the “Internal assessment” section of the

guide.

2. Set a timetable for the different stages, for example, choosing the topic, first draft, and

final version.

3. Discuss topics and advise students to change unsuitable topics.

4. Guide students in the selection of appropriate and available sources.

5. Give guidance on how to tackle the exercise, emphasizing in particular the importance of

a well-defined research question, gathering evidence, the use and evaluation of sources,

analysis, and the use of a standard system for references and the bibliography.

6. Read the students’ first drafts (this can be done in sections) and advise them how their

work could be improved, but do not annotate the written draft heavily.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

32

7. Check the authenticity of the student’s draft to confirm that, to the best of your

knowledge, it is indeed the work of the student. If malpractice, such as plagiarism or

collusion, is identified before the coversheet has been signed by both the teacher and the

student, the issue must be resolved within the school. For further details about academic

honesty refer to the Handbook of procedures for the Diploma Programme and the

IB publication Academic honesty available on the OCC.

8. Mark and comment on all internal assessment work according to the criteria in the guide.

9. Make copies of internal assessment pieces selected for the sample to be sent to the

moderator.

10. Ensure that you have signed forms 3CS and 3IA.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

33

Appendix F: Glossary of Command Terms

Candidates should be familiar with the following key terms and phrases used in examination

questions. Although these terms are used frequently in examination questions, other terms may

be used to ask candidates to present an answer in a specific way.

account for Asks candidates to explain a particular happening or outcome. Candidates are

expected to present a reasoned case for the existence of something.

For example: In 1970 the President Nixon authorized the CIA to carry out covert operations

aimed at deposing the popularly elected president of Chile. Account for this decision.

analyse Asks candidates to respond with a closely argued and detailed examination of a

perspective or a development. A clearly written analysis will indicate the relevant interrelationships between key variables, any relevant assumptions involved and also include a

critical view of the significance of the account as presented. If this key word is augmented by

"the extent to which" then the candidate should be clear that judgment is also sought.

For example: Analyse the political and economic changes caused by the Depression in one

country of the region.

assess Asks candidates to measure and judge the merits and quality of an argument or concept.

Candidates must clearly identify and explain the evidence for the assessment they make.

For example: “The Great Depression changed government’s views of their role and

responsibility.” Assess the validity of this statement with examples taken from two countries in

the region.

compare/compare and contrast Asks candidates to describe two situations and present the

similarities and differences between them. On its own, a description of the two situations does

not meet the requirements of this key word.

For example: Compare and contrast the Cold War Policies of Truman (‘45-’53) and Eisenhower

(‘53-’61).

define Asks candidates to give a clear and precise account of a given word or term. Do not use a

word to define itself.

For example: Define the term "success ethic" with regard to the depression era.

describe Asks candidates to give a portrayal of a given situation. It is a neutral request to present

a detailed picture of a given situation, event, pattern, process or outcome, although it may be

followed by a further opportunity for discussion and analysis.

For example: Describe how the events of the Great Depression brought about economic changes

in Latin America.

Dollison: IB History of the Americas, Skills Handbook

34

discuss/consider Asks candidates to consider a statement or to offer a considered review or

balanced discussion of a particular topic. If the question is presented in the form of a quotation,

the specific purpose is to stimulate a discussion on each of its parts. The question is asking for

the candidate's opinions; these should be presented clearly and supported with as much empirical

evidence and sound argument as possible.

For example: Discuss how the outcome of Second World War, in part, caused the Cold War.

distinguish Asks candidates to demonstrate a clear understanding of similar terms.

For example: Distinguish between the goals of the First and Second New Deal.

evaluate Asks candidates to make an appraisal of the argument or concept under investigation or

discussion. Candidates should weigh the nature of the evidence available, and identify and

discuss the convincing aspects of the argument, as well as its limitations and implications.

For example: Evaluate President Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima in

1945.

examine Asks candidates to investigate an argument or concept and present their own analysis.

Candidates should approach the question in a critical and detailed way which uncovers the

assumptions and interrelationships of the issue.

For example: Examine the influence of Kennan’s “long telegram” on the U.S policy of

containment.

explain Asks candidates to describe clearly, make intelligible and give reasons for a concept,

process, relationship or development.

For example: Explain why the United States become involved in the Second World War?

identify Asks candidates to recognize one or more component parts or processes.

For example: Identify significant treaties between the United States and the Soviet Union

designed to slow nuclear proliferation .

outline Asks candidates to write a brief summary of the major aspects of the issue, principle,

approach or argument stated in the question.

For example: Outline the causes and course of the Korean War.

to what extent? Asks candidates to evaluate the success or otherwise of one argument or

concept over another. Candidates should present a conclusion, supported by arguments.

For example: “The Vietnam War had a disastrous effect on the presidencies of Lyndon Johnson

and Richard Nixon.” To what extent do you agree with this statement?

© Copyright 2026