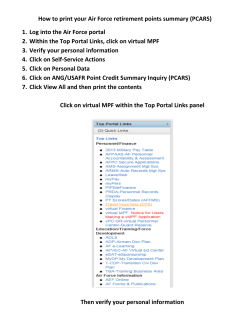

How to get personas to conform A Master’s thesis by Anders Ryman