György Boda dr., Judit Lőrincz, Péter Szlávik

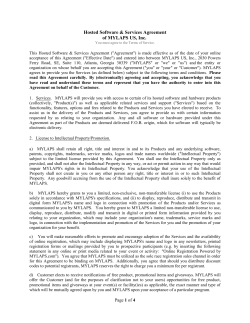

György Boda dr., Judit Lőrincz, Péter Szlávik HOW TO BE MORE EFFICIENT IN MANAGEMENT OF THE MOST IMPORTANT PRODUCTION FACTORS Practical approaches for the management of complex assets ________________________________ The Icfai University Journal of Knowledge Management, September 2008, Vol. VI No. 5, ISSN 0972-9216 INTRODUCTION It becomes more and more obvious that the proportion as well as the importance of tangible assets gradually decrease among production factors1, while the importance of intellectual assets is continuously increasing. It seems that managers are still very sceptical of using scientific methodologies as theoretically adequate methods to manage immaterial, intangible or knowledge production factors. The corporate decision makers are often doubtful about the uncertainties assigned to these methodologies, as they do not see the clear connection between the expenditures invested in these assets and the revenues generated by them. But is it really a dead end or are there some other ways to make some progress in different domains of Intellectual Capital Management? This is the main question we try to explore and answer in this paper. As a first step, we examine the most important production factors (chapter 1.). Secondly, we try to describe those unexplored management areas where managers are also lacking adequate management tools (chapter 2.). Finally we make an attempt to show the promising directions for the future (chapter 3.). THE MOST IMPORTANT PRODUCTION FACTORS The majority of economists agree that the role of tangible assets – lands, buildings and machinery – is not as significant as it was in the past. Nowadays the proportion of less material-intensive sectors is constantly growing, while the role of material production factors is decreasing even in the material-intensive sectors. The weight of service based 1 All elements that are necessary for the operation of the company, including financial capital, human capital, physical assets, etc. 1|Page corporate activities in the contribution to GDP is already higher than the total proportion of agricultural and industrial activities (see first part of Figure 1). Parallel to the increasing role of the service sector the proportion of intangible elements of production factors (e.g. competency, client and organization related assets) is also growing. A significant part of intangible production factors is represented by people. The growing importance of this human factor is accompanied by the evolution of human freedom. Capital owners of physical assets will face challenges in this new environment. They used to control the economy by owning the physical (tangible) production factors, however these days as a result of the previously described tendency a significant part of production factors are owned by the people themselves2, who are not closely tied to these original capital owners. This means the fall of the monopoly of conventional capital. Due to this the capital owners need new management techniques to better control the mix of production factors. 2 E.g.: customer relationships, knowledge, innovation capability, etc. 2|Page Figure 1. The changing role of production factors 3 100 % The main economic sectors Services Proportion Industry Agriculture 0% 100 % The role of production factors Competency Proportion Other physical assets Client, organizational assets Land 0% 100 % The human commitments Proportion Free people Vassal Slave 0% Time The Collapse of The Roman Empire The French Revolution The Industrial Revolution Some parts of intellectual capital are easier to control than others. Therefore company managers should concentrate on those intellectual production factors which are more manageable. If the management of intellectual capital4 is at least partly solved, then a 3 This chart was made based on the tendencies of the well developed OECD countries. 4 The ownership of intellectual assets. In the general terminology these categories (intellectual assets and intellectual capital) are often used as synonyms. 3|Page certain part of the intellectual capital will be controlled and owned by the company and its owners. Managers are familiar with the bookkeeping recommendations of the Accounting Laws and Regulations, or the International Accounting Standards. And they surely know the balance sheet itself, which shows the assets of a firm. But are all the important assets taken into account in regular balance sheets? Not entirely. Conventional accounting does not support the overview of both tangible and intangible production factors. Let’s think about clientele of companies, organizational factors, or knowledge and competence of employees, which are all basic elements of corporate operation and are essential in generating profit. None of these elements are presented in the conventional balance sheet. Therefore instead of the official, conventional balance sheets, company owners and managers should think according to the more complex Total Asset Model shown in Figure 2. 4|Page Figure 2. The most popular Total Asset Model5 Assets Cash Liabilities Short-term liabilities Long-term liabilities Current assets Visible assets Tangible assets (Machines, buildings, computers, etc.) Shareholders’ visible equity Intangible assets (Software, property rights, etc.) Becomes visible in case of mergers & acquisitions Network assets (External structure: prosperous relationship with customers, suppliers and the micro-environment. E.g.: brand names, trademarks, reputation, image, etc.) Shareholders’ invisible equity Organizational assets (Internal structure: good management and company structure, prosesses, used methodologies, concepts, models, theories, standrads, IT and administrative systems, corporate culture, etc.) Individual’s competence (Ability to create material and immaterial assets. Employees’ capacity to act in various situations, which includes skills, education, experience, etc.) Invisible assets Intangible liabilities (Legal cases, commitments related to long-term employment, commitment to maintain product and service quality, constraint related to PR and marketing) The „Invisible” Balance Sheet Source: Karl-Eric Sveiby © The Total Asset Model expands the traditional balance sheet with new corporate production factors such as relationship assets or organizational assets. One could say that invisible6 assets are “under the surface” and clearly separated from the well-known visible assets. If we consider it from the ownership point of view, it becomes obvious that these invisible assets are differentiated by the possibility of ownership. A part of the invisible equity is owned by the shareholders, while another part is similar to debts and obligations. The exact proportion of shareholder’s invisible equity and intangible debts and obligations depends on how well the intangible assets are managed. The Total Asset Model attracts attention among managers, because unlike conventional accounting reports it takes into account the complex production factors. This model is very important in visualizing the invisible intangibles, but like all models it has some misleading elements. The Total Asset Model gives the illusion that the assets – tangible 5 Detailed description of originals (Edvinsson, Sveiby, Stuart, etc.) 6 Invisible, intellectual and intangible terms are used as synonyms throughout the text. 5|Page and intangible – are isolated and clearly separated from each other. In addition to this illusion of separation there is another imperfection with this Total Asset Model. In our current belief there is one more intellectual asset missing from the model. Some years ago we have met and soon entered into partnership with a Belgian consulting company named AREOPA7. This cooperation helped us to widen our view and to share knowledge. From our Belgian partner we have learnt a new model8, which gives a much more realistic and complex depiction of the corporate assets (see Figure 3.). Beyond that, what we have learnt from AEROPA is not only that there exists a better model in which the traditionally known and the newly recognized production factors are combined and closely interrelated, but also that another production factor exists, which the Total Asset model shown in Figure 2. does not mention: the strategic alliance capital. Figure 3. AREOPA 4-leaf® Model Structural IC level SC SC Structural capital High SC-HC SC-HC-SA SC-HC-SA-CC HA SC-HC Human capital HC-SA SC-HC-CC SC-SA SC-HC-SA SC-HC- SC-HC-CC SA-CC SC-SA-CC HC-CC SC-CC HC-SA-CC SA Strategic alliance capital SCSA SC-SA-CC SA-CC HC SCCC CC HC-SA Customer capital HC-SA-CC HCCC SA SA-CC CC Low The model clearly presents that there are overlaps among the four main production factors. For example the value related to a customer – that we know due to the cooperation with one of our strategic partners (i.e. subcontractor with specific knowledge) – is presented in SA-CC category. 7 www.areopa.com 8 The model is called AREOPA 4-leaf Model® 6|Page For each segment of the 4-leaf model, AREOPA has developed a series of econometric calculations and related questionnaires which allow the calculation of segment’s value. Our fundamental economic instincts – based on our culture which we have inherited from the Greeks – force us to compete. For continuous development in economy some competition is generally needed, but total competition without any cooperation isn’t always profitable or effective. If companies do not regard competition as the only way of creating value, they could gain a lot immediately. This is especially true for production factors derived from knowledge. Their sharing does not mean that the one who shares will have less. The opposite result is more likely, and our experience shows that the one will have more, if the rule of sharing is respected and carefully kept9. After studying AREOPA’s 4-leaf model we made some extensions to it and by doing this we defined a new total asset model. There are two major differences between the original 4leaf model and the extended one: 1. We have presented the tangible assets that have strong interrelation with intangibles. 2. We have replaced the “capital” by “asset”. By doing this we would like to emphasise that the existence of an intellectual element has an asset type of manifestation (i.e. the intellectual element is identifiable and measurable). On the other hand in case of every asset we can investigate the ownership structure (i.e. up to what proportion the company owns, therefore controlls the asset). In this aspect “capital” refers to the ownership structure (similar to liabilities side of the balance sheet). 9 The rules of sharing intangibles are much more complicated than sharing the tangibles, which could be a topic of another paper. 7|Page Figure 4. Extended Total Asset Model based on the AREOPA 4-leaf® Model10 Structural IC level Tangible assets SA High SA-HA SA SA-HA-SAA Structural asset SA-HA-SAA-CA SA-HA-CA HA SA-HA Human asset HA-SAA SA-SAA SA-SAA-CA SA-HA-SAA SA-HA- SA-HA-CA SAA-CA SA-CA HA-CA HA HA-SAA-CA SAA Strategic alliance asset SASAA SA-SAA-CA SAA-CA SACA CA Customer asset HA-SAA HA-SAA-CA HA-CA SAA SAA-CA CA Low In this adjusted 4-leaf model (Figure 4.), tangible assets complete the intangibles, and thus without the intangible assets there would be a gaping hole. In this sense the tangibles are depending on intangibles and not conversely. A good example of the interrelationship between tangibles and intangibles is when obtaining a computer without having the proper knowledge to use it there is an asset in the balance sheet which brings no added value to corporate operations and therefore to the value of the enterprise. On the other hand if there exists the specific knowledge needed to use the new computer, value is added to the enterprise which is already larger than the purchase price of the computer. The coloured scales on the right side of the Figure 3. and 4. describe how much we can structure and control each category. The higher the asset is presented on the scale, and thus the more light-coloured it is, the more it can be owned and controlled by a company. In such a way this asset model gives a much more realistic overview about the sharing rules of intangibles among their owners. This concept cannot be complete without examining the relationship between intangibles and knowledge, so we should investigate what are the components of knowledge. Valuable knowledge always has both explicit and tacit elements, which are present in intellectual 10 In this figure we have completed the 4-leaf Model of AREOPA with the dimension of tangible assets. By doing this we would like to emphasize that the presence of intellectual capital is always closely relating to tangible assets. 8|Page capital. Both Figure 5. and Figure 6. show that owning all elements of knowledge is impossible. Figure 5. The tacit dimension – I. Information Management Knowledge Evolution Expertise Experience Know-how Knowledge Information Data Bits & Bytes + Syntax + Semantics + Context + Use Explicit Knowledge + Practice + Efficiency Tacit Knowledge Intellectual Capital Knowledge Building Process & Intellectual Capital Source: Ludo Pyis, AREOPA Figure 6. The tacit dimension – II. Dependency on the knowledge carrier Wisdom Knowledge Information Data Understanding The Data-to-Wisdom curve Source: Gene Bellinger, Durval Castro, Anthony Mills 9|Page From Pollányi we know that the greater the knowledge is the more personal and individual it becomes11. That means a big risk for the intellectual capital investors, because only bits, bytes and explicit knowledge can be owned without taking any risk. As personal knowledge increases, the value of the company does as well, however it is linked to the person who carries the knowledge. Likewise the deeper the knowledge is, the bigger the risk is that if the knowledge-owner (the employee) goes away the investor (the employer) will suffer grave loss. That is the reason why we should focus on the management of these new production factors which cannot be separated from knowledge management. This dependency on the knowledge carrier could be even greater as client and organizational assets are also linked to the knowledge he/her possesses. Just think of the following. It often happens that consulting companies suffer loss in client assets when a good client follows the dismissed consultant to the new employer consulting firm. Another example is when the retirement or departure of some IT experts makes the system unusable and often results in a total ERP reengineering. To summarize the main points of our thoughts we can say, that greater wealth needs bigger intellectual capital, but investing into intellectual capital also brings higher risk. In order to be able to effectively manage intellectual capital, the decision makers should face (and answer) the following questions: • Where and how to invest into intellectual capital with maximal result and minimal risk? • How to keep the value and the stability of the investment and how to avoid the risk of losing it? To answer these questions, intellectual assets need precise measuring. How to measure intangibles will be described in the next chapter. UNEXPLORED MANAGEMENT AREAS Science and efficient management begin with measuring. Everybody is familiar with the well-known management slogan: “what cannot be measured cannot be managed”. We think it is true only in the following form: “what cannot be measured cannot be efficiently managed”. As we will show, there are some difficulties in measuring intangibles, which is the main reason why their exact measurement is only in an initial stage. 11 Pollányi: The Tacit Dimension. 10 | P a g e To show the current status of intangible measuring methods, Karl Erik Sveiby’s classification is the most convenient summary (see Figure 7.). Figure 7. Karl-Erik Sveiby’s classification of methodologies to measure immaterial assets Market-to-Book Value ORGANISATIONAL LEVEL ONLY (MCM – 1997/98 – Stewart/Luthy) MCM MARKET CAPITALISATION METHOD The Invisible Balance Sheet Knowledge Capital Earnings (MCM – 1989 – Sveiby) (ROA - 1999 - Lev) ROA Value Added Intellectual Coefficient - VAICTM Calculated Intangible Value (ROA - 1997 – (Public)) RETURN ON ASSET METHOD (ROA – 1997/98 – Stewart/Luthy) Economic Value Added - EVA TM DIC (ROA - 1997 - Stewart) TM TM IC-Index BusinessIQ (SC - 1997 - Roos & al.) IC RatingTM (SC - 2004 - Sandvik) DIRECT INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL TM Investor Assigned Market Value - IAMV (MCM – 1998 – Stanfield) Value Chain Score BoardTM Citation-weighted Patents (SC - 2002 - Lev) (DIC - 1996 - Bontis) Human Resource Costing & Accounting - HRCA 1 SC SCORE CARD METHOD (DIC - 1988 - Johansson) (SC - 2002 - Edvinsson) COMPONENTS IDENTIFIED Tobin’s q (MCM – 1950's – Tobin) Human Resource Costing & Accounting - HRCA 2 Skandia NavigatorTM (DIC - 1970's - Flamholtz) (SC - 1994 – Edvinsson/Malone) HR Statement Balanced Score Card Intangible Asset Monitor Inclusive Valuation Methodology (SC - 1992 – Kaplan/Norton) (SC - 1994 - Sveiby) (DIC - 1998 - Mc - Pherson) Danish guidelines (SC - 2003 – Mouritzen & al.) Meritum guidelines Knowledge Audit Cycle (SC - 2002 - (EU)) (SC - 2001 – Marr&Schiuma) The Value ExplorerTM (DIC - 2000 - Adriessen&Tiessen) Total Value Creation - TVCTM (DIC - 2000 – Aderson&McLean) Technology Broker (DIC - 1996 - Brooking) NO MONETARY-VALUATION (DIC - 1990 - Ahonen) Intellectual Asset Valuation (DIC - 2000 - Suvillan) Accounting for the Future - AFTFTM (DIC - 1998 - Nash) MONETARY-VALUATION Intangible Assets Measurement Models Source: Karl-Erik Sveiby © As it’s visible from this classification there is a large number of existing measurement techniques. Mr. Sveiby classified the measurement methods based on the approach and characteristics of each method. The two dimensions of the matrix refer to the level of measurement focus (aggregated vs. disaggregated) and to the type of the measurement (monetary vs. non-monetary). The different colours show the different measurement method categories: Market Capitalisation Method, Return On Asset Method, Direct Intellectual Capital and Score Card Method. The distribution and the position of the coloured boxes among the quadrants shows that certain methods refer to certain approaches (i.e. Direct Intellectual Capital methods are useful in case we want measure the monetary value at the components level). Let’s examine the quadrants separately! In the upper left quadrant the measurement is practically impossible, which means that it has no point to measure aggregated nonmonetary values. Significant results have been achieved in the design of measurement techniques belonging to the upper right quadrant. The company valuators have realized long ago that there is a difference between market and asset value of a company. The development and use of “Tobin’s Q” methodology was its famous manifestation. “Tobin’s Q” 11 | P a g e basically analyzes the difference between the market value and the book value of the company in total monetary format. Actually, in everyday practice there are three popular methods to calculate the market value of a company. These are the following: 1. The market capitalization method (MCM): when the number of issued shares is multiplied by the market price of the shares, where this total amount is regarded as the market value of equity. For the calculation of enterprise value the market value of equity and the value of short and long term liabilities are combined. 2. The discounted cash flow method (DCF): when a company’s forecasted future free cash flows are discounted by the cost of capital of a company and that is all added up. 3. The comparison methods: in cases when we both lack stock exchange information and the knowledge of the company’s business plan, the appropriate way of valuation could be the one made on comparisons. In this case we need exact information about realized M&A transactions of similar companies, and we use these transactions’ key indicators (for example EBITDA multiple) to apply these to our company valuation. Any of these three valuation approaches provides us information about the market value of a company, from which we deduct the book value, and this gives us a rough calculation of the intellectual capital value. The aggregate monetary approaches are not useful in everyday management because they only tell some information about the firm in total and do not give any help in answering detailed management issues. Despite this fact, these approaches have important contribution in attracting the attention of managers to the existence and importance of intangibles. Tremendous effort has been made in the lower left quadrant. Several of these methods became widely known and highly popular. These methodologies are for example the Scandia Navigator of Edvinsson and Malone, the Intangible Asset Monitor of Sveiby, the balanced scorecard of Norton and Kaplan, the Koch-Schneider-Nagel model, the EFQM methodology, etc. Although these methodologies do not measure an exact value of intangibles, they create awareness in managers that intangibles should be managed. Besides, it provides guideline for managers about what to manage as intangibles or what kind of intangibles they should manage and control. The biggest unknown field of intellectual capital calculation methods is the lower right quadrant. Although a lot of methodologies have been developed, there is not one widely accepted methodology to evaluate the separate, specific elements of intangibles. 12 | P a g e There are continuous efforts to define accepted approaches for the measurement of disaggregated intellectual capital elements. • Some efforts are made to measure the expenditures/costs which are invested in certain intangible assets. But the valuation from the cost side is far from being accurate. The value of an asset is rather determined by the generated future cash flows, than by the replacement cost of that asset. Moreover because of the interpenetration of different intangible assets, we cannot clearly connect the intangible assets and the future cash flows. • The previously presented AREOPA model focuses on this measuring direction and has developed a set of econometric equations to measure the elements intellectual capital. In spite of these attempts we already mentioned above, there is no widely accepted methodology which could measure the intangible elements separately and which could connect their calculated amount to the results measured by the upper right methodologies. The existence of total intellectual capital value we only know from already existing total asset models but we cannot show an approach that is summarizing it from bottom to top. With methods in the upper right quadrant we can guess their total amount, while with the scorecard methods we can link scorecard indicators to the focused intangible elements, which might show the improvement or decline of these asset elements. But we do not know anything exactly about their individual value. We should recognize that in this field managers appreciate useful and reliable solutions. Without direct intellectual capital valuation methods managers cannot precisely answer the questions; where and how to invest into intellectual capital with maximal result and minimal risk, how to keep the value and the stability of the investment and how to avoid the risk of losing it? In lack of precisely calculated answers, smart guesses can help in decision-making and managing the intellectual assets (Like the Intellectual asset monitor of Sveiby in Figure 8.). If the percentage of image enhancing clients is constant and if the revenue per clients or the number of repeated orders grows, then the client asset base of the firm is more likely to be strong and powerful (see the first column in Figure 9). If number of repeated orders grow, if the rookie ratio is not declining, and if the employee satisfaction is constantly high, then we probably have stable intangibles and we do not face big risk of losing it (see the last raw in Figure 8.). 13 | P a g e Figure 8. Sveiby’s Intellectual Asset Monitor for CELEMI – an example for quick win scorecard method Client Organization Ex terna l structure Interna l structure Competency Average professional experience (years) R&D/revenues (%) Image enhancing clients (%) 16% 80% 16.0 Growth, renewal 70% 14% 60% 12% 50% 10% 40% 8% 30% 6% 6.0 20% 4% 4.0 10% 2% 14.0 12.0 10.0 8.0 2.0 0% 0% 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 0.0 1997 2002 Revenues per client (TSEK) 1998 1999 2000 2001 1997 2002 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Value added per expert (TSEK) Revenues per admin staff (TSEK) 1,400 700 1,200 18,000 600 Efficiency 16,000 500 1,000 14,000 800 12,000 400 10,000 600 300 8,000 6,000 200 400 4,000 100 200 2,000 0 0 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 0 1997 Repeat orders (%) 1998 1999 2000 2001 1997 2002 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 People satisfaction index (%) Rookie ratio (%) 80% 90% 60% 70% 80% 50% 60% 70% Stability 60% 40% 50% 30% 40% 50% 40% 30% 30% 20% 20% 20% 10% 10% 10% 0% 0% 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 0% 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 These are all important reasonings and good starting points in decision-making, but they do not tell exactly whether we underinvested or overinvested in intellectual assets. Competition in business compels us to carefully balance our investments. However the scorecard evaluation is not the most precise measurement, still it is a good starting point and a feasible direction by giving help for managers when there is nothing else to reinforce intuitions and corroborate decisions. Presently, the scorecard measurements are better and cheaper solutions and even more reliable quick wins, than the DIC calculations. But the future is theirs, as only DIC methods are able to reduce costs of erroneous management decisions and solve the careful balancing of investments in intangibles, just as it is more or less solved in the tangible world (see Figure 9.). 14 | P a g e Figure 9. Scorecard vs. DIC measurements Costs generated by erroneous decisions Scorecard measurements DIC measurements Time PROMISING DIRECTIONS Life and business do not stop. Managers do not have time to wait. They are compelled to act and they have to do it. What are the directions of development in intellectual capital management? Due to our practical experiences we believe that some directions could be far-reaching in the future. Innovation in the field of Intellectual Capital Management could possibly mean the followings: 1. Focusing on human resources controlling. 2. Connecting scorecards to processes. 3. Moving on from handling crowds of employees to managing individual employee profit centers. Focusing on human resources controlling If production factors are carried by people, the controlling must be focused on human resources! But what does it mean exactly? Traditional controlling is focused on organizations. The most popular controlling model - the master budgeting controlling model12 - is principally based on the company structure. Only 12 We have published several books and related business models in this field. Please refer to the reference list. 15 | P a g e the minority of the firms means an exception to this rule and instead of organizational structure it uses activity maps or process maps as the basis of developing effective controlling systems. In this way most controllers are only controlling departments as separated boxes – many times as black boxes – of a company and not the company as a whole. Thus they cannot do more than to act according to the “lawnmower principle:” if a department operates badly, than it must be regulated by cut in costs. In reality, as the harmonizing of the external market to environmental requirements becomes more and more important, the real stakeholders within the firm gradually disregard the barriers of organizational structure, and pass over the problematic question of power and subordination. In this way they begin to give preference to the processes of the company. Corporate working processes are crossing the limits of organizational structures, and thus processes are rather relying on cooperation of people than on separate organizational units. The evolving of matrix organizations is a sign of this change in the way of business thinking. As a consequence, the focus of the controlling should be taken from departmental level to the hand off process level13, where task are carried out by a person or by a group of people. On this level the performing people become the targets of controlling, and in this way real production factors become the target of management. The process examining methodology on this hand off level is well described by the AREOPA TAPE model (see Figure 10.). If we follow the principles laid down in this matrix we secure the maximal client satisfaction, e.g. we promote the most efficient work processes which strengthen both the organizational and client capital. 13 Thinking processes could be examined on strategic level, on departmental level, on hand off level, on task level and even on motion level. For us here the hand off level is the relevant one, where the output is delivered by men to men, e.g. from hand to hand. 16 | P a g e Figure 10. The AREOPA TAPE grid Timeliness Accuracy Productivity Efficiency Product Does the customer get what he wants and when he expects it ? (being on time) Does the customer get exactly what he wants? (correct specifications) Is there an added value in each process step? Is there any rework in the process? How much of the work must be redone? Process information Does the customer get process information when he expects it? Does the customer get correct information? Does each information element have added value? Is information varying according to the moment? Does the commitment to timing create added value? Is the execution efficient? Does the process executor keeps his word? Treatment: - Friendlyness - Owning the problem - Commitment to timing Is the problem of the Is the problem of customer being owned customer being accepted? at the moment he Is there a commitment expects it? to timing? Is the customer being Are involved personnel treated friendly? friendly? TAPE® grid Source: Ludo Pyis, AREOPA This shift in the focus of controlling has a relevant effect on product, even if it is not the main output: future cash flows can be connected to hand off processes and because people can be directly connected to processes, hereby there is a considerable chance that people can be connected to future cash flow through processes. Connecting scorecards to processes It is always a big question in all scorecard projects from where the most appropriate indicators should come. The large number of cancellation of such projects shows that the problem is not yet solved. On strategic level the indicators can be found more easily, but below that level we are often facing some bureaucratic distortions and when the major scorecard indicators are taken apart to individual indicators, they usually lose their strategy making power and often transformed to unpopular, unsupported administrative figures. The solution can be found also on process level, when the scorecard indicators are selected after the careful analysis of the matching between strategic goals and working processes (Figure 11.). 17 | P a g e Figure 11. Connecting scorecards to processes Strategic projects Process 1 Process 2 Process 3 Process 4 Process 5 Process 6 Process 7 Project 1 Project 2 Project 3 Project 4 Project 5 Project 6 Project 7 Strategic Processes Financial perspective Generating renewal STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES for example: Improving efficiency Increase and sustain profit-making capability Client perspective (customer, supplier) Learning & Operational perspective improvement (processes, structure) perspective 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 Efficient use of free cash flow Efficient margin management Efficient margin management Growth Central sales management Increase integrity with customers Make customers ready to buy more new products or request new services Satisfied customers Good relationship with suppliers Good infrastructure Have a „core team” 3 Increase and sustain profit-making capability Efficient use of free cash flow Outstanding HR management 2 Increase ROIC Maximize brand value Developing complex brand 1 Maximize brand value Increase shareholders’ value More effective and efficient operation Efficient time management Customized, professional internal structure (differentiation from multinationals) Maintain company culture Controlled risktaking Successful multicultural environment Operation under good management control Increase shareholders' value Increase ROIC Growth Developing complex brand Increase integrity with customers Make customers buy more products and services Central sales management Satisfied customers Good relationship with suppliers Controlled risk-taking Outsanding HR management Have a "core team" More efficient and effective operation Good company culture (maintaining it) Good infrastructure Efficient time management Successful milticultural environment Customized, professional internal structure Operating under good management Satisfied employees Satisfied employees Increase the personal values and the worth of the management Challenge creation Independent and efficient way of operation Contribute to personal development (training and education) Callenge creation Increase the personel values Contribute to personel development Independent and efficient way of operation Figure 11. illustrates the connection on strategic level. In this methodology we first define the strategic objectives and make a strategic map based on these goals. This also means that the strategic goals are arranged into a hierarchy. The next step of the exercise is the matching of the strategic objectives with the core business processes. The matching also means a gap analysis between the objectives and the current status. Based on the matching, development projects are defined. The development projects should cover the gap between the strategic objectives and the current status of the business. If the processes do not support the strategic goals, obviously the strategic goals will not be achieved. That gives strategic significance to the indicators of the main processes, which means that this kind of indicators would never be bureaucratized. If everybody believes in a strategy, than they will feel and accept the importance of the indicators. The other group of useful indicators comes from those projects which generate change in the working processes in order to promote the realization of strategic goals. The defined projects are the basic tools of changing the processes. So the most important project indicators become essential because without their fulfilment the strategy would not be achieved at all. In case of determining such indicators there is no danger of bureaucratization. In case the previously described process is completed at the hand-off level, we get useful indicators to manage people and to connect them with the output. 18 | P a g e 4 5 6 7 Moving on from handling crowds of employees to managing individual employee profit centers In case our efforts are done at hand-off level of processes, we have to differentiate people, who are making creative work and those, who are only doing repetitive work. By doing that on this level we arrive to the task of selecting the real knowledge carriers, the owners of the new production factors. Creative work always means solving something unsolved, doing something undone, hereby creating something new. On the contrary repetitive work means doing what is already solved and done before. These two approaches of work are different and cannot be controlled the same way. Creative workers, in many cases, form a special group inside organizations. They actually do repetitive work, as well, but it is based on a previous creative work that was made by themselves using methods they haven’t disclosed. This kind of work means a big risk for the investors, because the method and knowledge of solving problems is totally owned by the creative worker and cannot be duplicated. The controlling of the repetitive work is well known from Taylor, whose name could sound familiar for most managers. (see Figure 12.). Figure 12. Controlling employees doing repetitive work (The taylorian stop-watch) Number of direct employees = Planned volume of production (physical units) * Time needed for one unit of production (h/physical unit) / Maximal hours performable by a man (h/head/year) / Number of expected hours within the performable hours (h/h) Total time needed for production (h) Higher salary Salary adjusted to the number of expected hours Minimal workforce needed for production (head/year) Workforce needed for production (head/year) In this case the manager determines the quotient of the time needed to produce one unit of production (unit can be a service delivery as well) and multiplies it by the number of units 19 | P a g e produced. If the determined time is smaller than the working time, he can see it immediately and start to investigate the reasons. Creative work cannot be controlled this way, mainly because in creative work the key knowledge carrier cannot be controlled by a stop-watch. Creative workers can be only controlled by a period of time defined in advance. These creative workers often hear sentences, like: “You have this amount of time for the solution. If it is not enough, I will look for someone else who is able to solve it.” The result is dismissal, which may sound very cruel, but this is the only way of controlling this kind of work. Let’s see on Figure 14 how it is communicated politely! Figure 13. Controlling employees doing creative work (Time report) Number of direct employees = Number of hours planned to be charged (h/year) / Chargeability (h/h) / Maximal hours performable by a man (h/head/year) / Number of expected hours within the performable hours (h/h) Total time needed for production (h) Higher salary Salary adjusted to the number of expected hours Minimal workforce needed for production (head/year) Workforce needed for production (head/year) As mentioned above people doing repetitive work can be easily controlled by the Taylorian stop-watch, but this cannot be done likewise in case of creative workers, where the utilization of stop-watch is impossible. For creative workers the time report is the real solution. The main thing what a time report should reveal is how much time was used for the unit or units sold and how much for other purposes. In this way managers can check the chargeability and control the creative workers. In consulting companies, lawyer’s offices, or well organized universities creative workers – even students – usually get some chargeability requirements. For example: “50 percentage of your time should be sold to customers!” “In three years you should make your PhD!” Until the end of May you should finish your exams!” These sentences are the same as the crude sentence above. A certain output performance is specified within a given period of time, which is only a part of the total determined time for a given person. This is called chargeability. 20 | P a g e Chargeability also means: “I connect your activity to the output, which is important to me.” This way the managers are connecting the activities directly to output. Activities can never be done without activity owners. By measuring the chargeability of a certain group of people, whom we select not to be handled as crowds, but as individual profit centers. The output required of the knowledge carrier could be evaluated, such as the costs he generates and the profit made by him. It means once again a further step in connecting some intangibles to the output, which is the main purpose. In most organizations the Taylorian practice is the prevailing one, but this creative work system is gradually progressing in the form of special employee treatment programs which actually solve the specific controlling problems of knowledge carriers. It seems that the time of modern human resource controlling systems in Intellectual Capital Management are forging ahead, which development should be acknowledged and supported. SUMMARY During this paper we have briefly outlined the most important production factors and those related tendencies which have significant effect on management. We covered the definition of intellectual capital and we saw that the growing importance of the intellectual capital runs parallel to the growing importance of human factors. As intellectual elements get more focus, the management of the complex mix of production factors becomes more difficult. New reliable techniques are required for the continuous overview and management of intellectual capital. We cannot stop at the aggregate levels where monetary approach is more or less resolved; the details of intellectual assets should be grasped and understood. We saw that there are plenty of methodologies that are aiming to solve this, but there is still not available a widely accepted and known common approach. Until this issue is resolved, managers still face important questions, such as: • Where and how to invest into intellectual capital with maximal result and minimal risk? • How to keep the value and the stability of the investment and how to avoid the risk of losing it? Despite the uncertainties investigated, we still see promising new directions and useful management techniques that might provide valuable support until the ongoing economic revolution produces its widely accepted methods. These promising techniques link intellectual asset management to processes, and utilize those valuation and scorecard methods that are already tested and well understood by the majority of economists. 21 | P a g e REFERENCES • Allee, Verna: The Future of Knowledge, Elsevier Science, USA, 2003. • Lev, Baruch: Intangibles: Management, Measurement and Reporting, Brookings Institution Press, 2001. • Brealey , Richard A. - Myers, Stewart C. - Allen, Franklin: Principles of Corporate Finance, McGraw-Hill/Irwin, New York, 2005 • Damodaran, Aswath (2001) The Dark Side of Valuation, Prentice Hall PTR, Upper Saddle River, 2001. • Davenport, Thomas H. - Prusak, Laurence: Working knowledge, Harvard Business School Press, 2000. • Edvinsson, Leif - Malone, Michael S. (1997) Intellectual Capital, Harper Collins, New York • Bellinger, Gene - Castro, Durval - Mills, Anthony: Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom, 2004., http://www.systems-thinking.org/dikw/dikw.htm • Boda, György - Peter Szlavik: Alternative Accounting to Manage Intellectual Capital; Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management (Vol. 5. Issue 1), Feb. 2007; www.ejkm.com • Boda, György – Szlávik, Péter: Kontrolling rendszerek [Controlling Systems], KJK-KERSZÖV Jogi és Üzleti Kiadó, 2005., ISBN 963 224 842 2 • Boda , György: A tudástőke kialakulása és hatása a vállalati menedzsmentre [The evolution of knowledge capital and its impact on management], 2005., Phd dissertation • International Accounting Standards 2003, IAS 36 and 38 • Juhász, Péter: Az üzleti és a könyv szerinti érték eltérésének magyarázata - Vállalatok mérlegen kívüli tételeinek értékelési problémái [Explanation of deviations between market and book value], Phd dissertation, Budapesti Közgazdaságtudományi és Államigazgatási Egyetem, 2003. • Kaplan, Robert S. - Atkinson, Anthony A.: Advanced Management Accounting. • Kaplan, Robert S. - Norton, David P. (2004) Measuring the Strategic Readiness of Intangible Assets, Harvard Business Review, 2004 February. • Kaplan, Robert S. - Norton, David P. (1996) The Balanced Scorecard, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts • Mills, Roger W. (1998) The Dynamics of Shareholder Value - The principles and Practice of Strategic value Analysis, Mars Business Associates Ltd., 256 pages. • Pulic, Ante: Measuring the Performance of Intellectual Potential, www.antepulic.com • Ridderstrale, Jonas - Nordström, Kjell A.: Funky business: Talent makes Capital Dance, Pearson Education, 2000. 22 | P a g e • Standfield, Ken (2002) Intangible Management, Academic Press, Boston • Stewart, Thomas A. (2002) The Wealth of Knowledge, Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London • Sveiby, Karl Erik: The New Organizational Wealth, Berreth-Koehler Publishers, Inc., San Francisco, 1997. • Sveiby, Karl Erik (2003) A Knowledge-based Theory of the Firm to guide Strategy Formulation, Paper presented at ANZAM Conference, Macquarie University Sydney, 2003 February. • Thomas A. Stewart: The Wealth of Knowledge, Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London, 2002. 23 | P a g e

© Copyright 2026