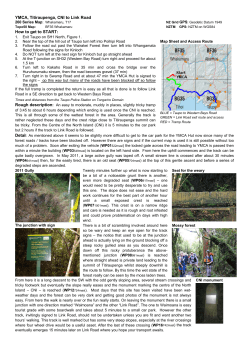

Document 198924