How to cope with the global value chain: Cristina Castelli

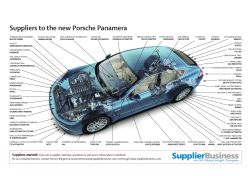

236 Int. J. Automotive Technology and Management, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2011 How to cope with the global value chain: lessons from Italian automotive suppliers Cristina Castelli Italian Institute for Foreign Trade (ICE), via Liszt, 21, 00144 Rome, Italy Email: [email protected] Massimo Florio Department of Economics, Business and Statistics, Milan University, via Conservatorio 7, 20122 Milan, Italy Email: [email protected] Anna Giunta* Department of Economics, Roma Tre University, via Silvio D’Amico 77, 00145 Rome, Italy Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract: In the past 20 years the automotive industry has been subject to fundamental changes, resulting in deverticalisation and dispersion of production across different regions. The structural changes strongly impacted on supplier firms localised in Turin (Italy), a hub and spoke district, featuring a wide supply chain polarised around Fiat Group, the lead company. Our case study examines the strategies implemented in the period 2000–2005 by a group of 13 selected suppliers, located in Turin area, to successfully participate to the global value chain. Our findings show that companies are pursuing a ‘high road development strategy’, based on client portfolio diversification, product and process innovation, cumulative internationalisation. More in general, future prospects for the local firms to survive international competitive pressures seem crucially depending on continuous learning and innovative firms’ activities. Keywords: automotive industry; hub and spoke district; fragmentation; global value chains; innovation; internationalisation, Turin; Italy; Fiat Group. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Castelli, C., Florio, M. and Giunta, A. (2011) ‘How to cope with the global value chain: lessons from Italian automotive suppliers’, Int. J. Automotive Technology and Management, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp.236–253. Biographical notes: Cristina Castelli is employee at the Italian Institute for Foreign Trade (ICE, Rome, Italy) and involved in research projects of CSIL (Centre for Industrial Studies, Milan). Her main research interests lie in firm’s internationalisation processes, fragmentation of production as well as trade policy issues. Copyright © 2011 Inderscience Enterprises Ltd. How to cope with the global value chain 237 Massimo Florio is Professor of Public Economics and Head, Department of Economics, Business, and Statistics, University of Milan. His main research interests include applied welfare economics, project evaluation, privatisation, public enterprises, regional policy, industrial policy. He has been involved in several projects by the European Commission, the European Investment Bank, the European Parliament, the OECD, the World Bank and other international bodies. Anna Giunta is Professor of Applied Economics at the Roma Tre University. She is co-editor of QA – Rivista dell’Associazione Rossi-Doria, Franco Angeli Publisher, Milan; member of the scientific committee of Rivista Economica del Mezzogiorno, Il Mulino Publisher; member of the CSIL (Centre for Industrial Studies, Milan) scientific committee. She has been scientific supervisor of several research groups and consultant to organisations and institutions such as the Ministry of Economy and Finance, Ministry of Industry, Capitalia Research Department, Svimez. Her current research interests are firms’ organisation and internationalisation, firms’ boundaries and ICT, firms’ growth, industrial and regional policy evaluation. 1 Introduction and research motivation As stated by several authors (e.g. Jones and Kierzkowski, 1990; Feenstra, 1998; Arndt and Kierzkowski, 2001; Hummels et al., 2001; Jones and Kierzkowski, 2005), in the past 20 years the production of a final commodity can take place through a vertically integrated process or by ‘production blocs’ separated by distance, located in the same country or abroad, that can be either under the control of the same firm or performed by independent companies. Fragmentation of productive processes, facilitated by service links in the form of transportation, communication and other coordinating activities, may lead to an increased dispersion of production worldwide, while simultaneously encouraging national agglomeration (Jones and Kierzkowski, 2005). Against this background, insights deriving from another strand of literature, the Global Value Chain Analysis (GVCA, henceforth) are very useful to describe the context and the current trends in the automotive sector, where centrifugal and centripetal forces are determining the location of production (Sturgeon and Florida, 2004; Gereffi et al., 2008; Gereffi et al., 2009). The GVCA – first proposed by Gereffi (1994) and then followed by a number of contributions (Gereffi and Korzeniewicz, 1994; Kaplinsky, 2000; Henderson et al., 2002; Humphrey and Schmitz, 2002; Sturgeon et al., 2008) – focuses upon firms’ dynamics, suggesting that the positioning of a firm and its upgrading along the global value chain, as well as the pattern of governance of the chain it feeds into, are crucial in determining its growth performance. Gereffi (1999) outlines a distinction between two types of production chains: a buyer-driven commodity chain – common among labour-intensive industries such as textiles and shoes – and a producer-driven commodity chain – typical of industries such as automotive, electronics and civil aviation. Global value chains are usually characterised by a leading company with coordinating and controlling function, hosting several ‘global production networks’ consisting of subsidiaries, affiliates, subcontractors, suppliers, partners in strategic alliances located in different countries. Competitive success increasingly depends on the capacity 238 C. Castelli, M. Florio and A. Giunta of managing effectively these global networks (Sturgeon and Florida, 2004) and on sourcing in a selective way from vertically specialised firms (Ernst, 2005), taking advantage of the progress in Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs, henceforth) to coordinate productive processes located in different parts of the world. The main research question of the paper is to analyse to what extent firms, based in the Turin province (Piedmont Region, Northern Italy), a hub and spoke district, for long time operating in a local context under quasi-monopsonistic relationship with Fiat Group and regarding foreign markets prevalently as outlet markets, are able to successfully participate into the global value chain. In order to fulfil our research questions, we analyse the main strategies that have been adopted by these firms in the Turin district to take part in the global value chain. In particular, we analyse, by means of a case-study, how a group of selected suppliers, belonging to different segments of the automotive production chain, is facing both the international reorganisation and, at the same time, the profound crisis of the Italian lead group, from which it partially recovered only after 2005. Our analysis was conducted on 13 firms by means of direct interviews,1 taking into consideration several structural, organisational and performance variables related to the 2000–2005 period, years marked by the most severe crisis of the lead Italian Group. In order to analyse which were the main firms’ strategies to accomplish successful participation in the global value chain, interviewees were selected among firms which met three out of four requirements: 1 operating in the upper part of the automotive suppliers’ pyramid (i.e. supply directly the car manufacturers and/or the ‘first tier’) 2 showing a satisfactory performance of turnover, that is above the average of the Turin Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Agriculture and Handicrafts (CCIAAT henceforth), sample equals to 5.6% during the reference period 2000–2005 3 being active on foreign markets, i.e. exporting a considerable share of total turnover: above the average of the CCIAAT sample equals to 39.4% 4 make extensive use of ICTs. The ratio of our choice was to investigate which were the strategies of firms positioned in the top section of the ‘pyramid’, more likely to succeed in the global value chain because of an ex ante higher productivity level, less at risk to be crowded out by competitors from emerging countries. The main limitations of our methodology come from the fact that results cannot be generalised to the whole automotive supplier firms’ population, as the firms interviewed are not statistically representative. Bearing in mind this caveat, nevertheless, the findings of our case study seem to have timely implications since Fiat, the Italian leader firm, has recently accelerated the ongoing restructuring of its spatial dimension, loosening its embeddings in the Turin district. Such a strategy will force Turin suppliers to look for alternative markets outlets abroad, thus facing the increasing challenges coming from the participation in the global value chains. The paper is organised as follows: Section 2 briefly traces the main features of the automotive industry and the changes of the international context in which the supply chain is currently operating. Section 3 supplies some evidence on the increasing integration of the Piedmont Region in international production networks. Section 4 illustrates the main results of our case study by focussing upon the main strategies adopted by a group How to cope with the global value chain 239 of selected firms in response to the structural changes. In Section 5, we will attempt to outline under what circumstances supplier firms will continue or discontinue their operations in the Turin district, and finally, Section 6 offers some concluding remarks. 2 The globalisation of the automotive industry: fragmentation of the value chain and geographical reorganisation The automotive industry can be defined as a ‘producer-driven’ global value chain, characterised by a high degree of concentration, resulting from a consolidation process that took place in the 1990s and is currently going on, driven by the international crisis. During the same years, a deep reorganisation has led to a deverticalisation of the industry and to outsource many activities, which was also made possible by the increasing modularisation of production (Frigant and Lung, 2002; Larsson, 2002; Sturgeon, 2002; Sturgeon and Florida, 2004; Frigant, 2007; Volpato, 2008). Accordingly, the automotive production chain is made up of a number of sections or levels (‘tiers’), at the top of which is the car manufacturer. In a context of increasing trade liberalisation and cheaper ICTs, the production chain has been fragmented among the countries of origin and abroad. Most car manufacturers have focussed on some core competences and perform in their plants mainly the final assembling of the vehicles, relying on a network of local and foreign suppliers. The latter can be located near the lead firms or may produce in other countries, depending on their product specialisation, the relevance of trade costs (packaging, transport, communication and coordination) and of delivery time, and may (or may not) refer to lower tier subcontractors. By establishing multiple foreign plants, automakers triggered the creation of different regional industrial systems, relatively close to the final markets, where production is typically clustered. In Europe there have been increasing investments in the new EU Member States, while Asia has become the region in the world where most vehicles are assembled (STEP-CCIAT, 2008), especially China and India playing a growing role. Compared to other industries, proximity to the final markets is particularly relevant because of the high transport costs of motor vehicles and their main parts, and due to the industry-wide adoption of lean production techniques, implying timely delivery and justin-time organisation. Hence, time and distance both act like an entry barrier and a trade cost; these two factors are of a growing importance for the choice of suppliers to be included in the production chain (Nordås, 2005), determining an increasing co-location near the automaker’s assembly plants (‘follow the client’ strategy, see Balcet and Enrietti, 2002; Humphrey and Memedovic, 2003; Frigant and Layan, 2009), as suppliers might otherwise lose their customers (Sturgeon and Florida, 2004, Gereffi et al., 2009). As regional poles develop towards what we can define ‘global districts’, where multinational affiliates and locally owned suppliers are setting their plants, carmakers (and multinational suppliers) may gradually replace international trade with arm’s-length contracts. In order to ensure high quality and reliability, suppliers are selected according to their financial and productive capabilities, and procurement is based upon two fundamental criteria: firms’ know-how and logistic costs. Whenever trade costs are high and suppliers need to be very specialised, carmakers tend to source locally or encourage the productive internationalisation of supplier firms from the home district; conversely, if the incidence of transport costs is low, the ‘global sourcing’ logic is adopted to purchase products worldwide, at the best price-quality ratio. 240 C. Castelli, M. Florio and A. Giunta Up to now, locally owned suppliers in emerging countries are considered competitive merely in price, while advanced countries’ manufacturers seem superior for all other factors such as reliability and technology. It follows that simpler, standardised, easy-tomake parts are increasingly sourced from local firms, while more sophisticated components are usually produced by subsidiaries of multinationals (Humphrey and Memedovic, 2003) relying, on turn, on their own production networks. Nonetheless, like in other industries, local producers can gradually increase their capabilities (Humphrey and Schmitz, 2002; Giuliani et al., 2005) and, in fact, the gap is rapidly shrinking, especially as Chinese and Indian engineers are improving their skills. This process is backed by carmakers’ strategies whose aim is to develop quality and reliability of a host of suppliers and to increase sourcing from locally owned firms. 3 The internationalisation of Piedmont Region Similarly to other carmakers, since the early 1990s, Fiat Group started restructuring the productive activities by locating plants worldwide, in different regions. The development of the spatial reorganisation process can be appreciated by looking at Table 1: while the EU still represents in 2007 the most important area for the Piedmont carmakers’ foreign investments in terms of turnover, the higher share of workforce relative to turnover in most emerging countries confirms that the more labour-intensive phases and lower end productions are located in these areas, which may function as export platforms (Table 1). Table 1 Foreign investmentsa performed by Italian car manufacturers of the Piedmont Region, as on 1 January 2007 (million Euros) Number of employees % share Turnover 27,586 37.4% 20,549 67.5% EU-15b 21,147 28.7% 17,405 57.1% EU-12c 6439 8.7% 3145 10.3% Other European countries 9854 13.4% 2442 8.0% Eastern European countries 4399 6.0% 275 0.9% Central and South America European Union % share 20,535 27.8% 5310 17.4% Asia 9280 12.6% 1445 4.7% Africa 1823 2.5% 182 0.6% 298 0.4% 260 0.9% 73,775 100% 30,463 100% Other countries Total Source: Processing of ICE-Milan Polytechnic Reprint data. Notes: aCommercial and productive FDIs. b EU-15 countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK. c EU-12 countries: Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia. How to cope with the global value chain 241 Following the geographical reorganisation of production operated by Fiat Group and other carmakers, the suppliers based in the Turin area have been increasingly involved in global production networks. On one hand, several first- and second-tier firms have ‘followed the client’, decentralising their production in the multiple regional industrial poles, where Fiat Group is operating. On the other, exports of parts and components originating from the Region experienced a steady growth, particularly after 2001, reflecting increasing intraindustry and intra-firm trade, especially with the EU Members of recent accession (see Figure 1). Imports have not grown much in recent years, as sourcing parts and components from low-cost countries is not (yet) a widely diffused strategy among Piedmont firms (although China and India play a growing role) and the final assembling of vehicles has been shifted to a considerable extent to other regions (Figure 1). Evidence from trade flows indicates also that neither the growing number of FDIs, performed by carmakers or by firms of the supply chain to locate near the lead customers, nor an increased local sourcing in the new regional poles, operated by carmakers and top suppliers, have substantially affected exports originating from the district and that, so far, Turin’s supplier seem to have been able to remain competitive (STEP-CCIAT, 2008). Figure 1 Piedmont Region: trade flows of car parts and components (thousands Euros) (see online version for colours) 6,000,000 5,000,000 Imports Exports Balance 4,000,000 3,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 20 08 20 07 20 06 20 05 20 04 20 03 20 02 20 01 20 00 19 99 19 98 19 97 19 96 19 95 0 Source: Processing of ISTAT data 4 The Turin automotive suppliers: the case study Against this background of global changes and increasing integration of the markets, in this section we analyse how a specific group of suppliers, located in the Turin district is facing the global context and which strategies have been chosen to take part in the international production networks and enhance their competitiveness. In-depth interviews were conducted with 13 firms, identified from the CCIAAT database that collects information on a representative sample of 786 firms of the automotive chain, out of a 242 C. Castelli, M. Florio and A. Giunta universe of an estimated 3500 firms. In order to analyse which were the main firms’ strategies to successfully participate in the global value chain, interviewees were selected among firms which met three out of four requirements, previously outlined (see Section 1). The ratio of our choice was to investigate which were the strategies of firms positioned in the top section of the pyramid, more likely to succeed in the global value chain likely because of an ex ante higher productivity level, less at risk to be crowded out by competitors from emerging countries. By examining the strategic approaches adopted during these years, our case study allows to understand the reaction of the firms to international competition and to the severe crisis of their most important customer, Fiat Group. With internationalisation processes becoming increasingly relevant, it also confers an in-depth insight about the various ways of participating in the global production networks (from merely exporting to the establishment of production plants abroad) and the related motivations. 4.1 Firms’ characteristics Apart from one foreign subsidiary, the firms considered in this case study are all Italian, mainly family owned and the majority of them does not belong to a group. Their productive activities widely differ and include the design and realisation of whole production lines (machinery, handling systems, automated warehouses), the design and production of systems (for example anti-vibrations components) as well as parts for motor vehicles (lighting, electro mechanics, aluminium objects for powertrain). Firms show a high and growing export propensity, as foreign sales represent on average 45% of turnover (compared to 34.6% in 2000) with peaks of 60–70%. Although their dimension considerably varies both in terms of employees and turnover, there is a net predominance of medium-large firms, a consequence of the fact that internationalisation processes are correlated with size, and this is particularly true when firms adopt more ‘complex’ internationalisation modes (Table 2). Table 2 Distribution of firms by size Number of employees Micro Small Medium Large <10 10–49 50–249 >250 Number of companies 0 2 7 4 Turnover (million Euros) <2 2–10 10–50 >50 Number of companies 0 3 7 3 Total 13 13 Source: Processing of balance sheet data With regard to firms’ positioning in the automotive value chain, as requested by our ex ante selection criteria, all companies supply directly the car manufacturers and most of them (10 out of 13) supply the ‘first tier’ as well, engaging in cooperative relations. Moreover, only a few firms supply the aftermarket, where competition is mainly pricebased and delivery time is less crucial than for parts entering the assembling process of a new car (Gereffi et al., 2009) (Table 3). Many supplier firms are in charge of their own supply networks, supported by a rather advanced endowment of ICTs to interact with customers and suppliers. How to cope with the global value chain Table 3 243 Distribution of firms according to the type of customer Number of firmsa Car manufacturer 13 Tier-1 supplier 10 Tier-2 supplier 4 After market 2 Source: Interviews a Multiple answers are allowed. Note: 4.2 Main strategies The global changes in the automotive sector have led firms of the supply chain to adopt a number of strategies, often used in combination with each other (Figure 2). In general, looking at the strategies which reported the highest ranking (between 4.17 and 3.50, in all figures the evaluation scale ranks from 1 to 5, where 1 = unimportant strategy and 5 = very important strategy), it seems that companies are pursuing a ‘high road development strategy’, based upon: (a) the expansion and diversification of their client portfolio, and here the different internationalisation modes play a crucial role, as we will shortly see. The finding is particularly relevant since until the mid of 1990s, most Turin suppliers firms mainly operated in a quasi-monopsonistic market (Enrietti and Withford, 2005); (b) the introduction of higher value-added products by investing in R&D and adopting product/process innovation2; (c) the involvement in productive internationalisation. These three aspects will be in-depth analysed in the following sub-sections. Investment in human capital, a crucial aspect to foster both innovation and internationalisation processes, scored on average a relatively high mark (very important for 7 firms out of 13), even though firms did not give much insights on this issue. Figure 2 Firms’ strategies (see online version for colours) 244 C. Castelli, M. Florio and A. Giunta 4.2.1 Customer expansion and diversification Following the prolonged crisis of the Fiat Group, the firms in the Turin district tried to accelerate the diversification of their customer portfolio in order to reduce the quasimonopsonistic dependence from Fiat Group (Calabrese and Erbetta, 2005). Our findings show that, in the period 2000–2005, several firms have been able to diversify their clients: only in two cases firms relied on Fiat for more than 50% of their turnover. As a result of customer diversification policy, firms recorded a considerable geographical extension of markets as well. In 2005, the then 15 Members of the European Union still represent the main market, while increasing shares are recorded by the countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and other emerging countries (Russia, Turkey, China), due to their growing importance as industrial poles and export platforms. The customer diversification strategy was backed in some cases by investments to set up foreign commercial branches in order to facilitate the penetration of the market (4 firms out of 13).3 Most of these suppliers are small-sized, and two use their commercial branch also to coordinate their local suppliers. A third one first established sales offices abroad (in UK), before deciding more recently to relocate part of its production in China. 4.2.2 Product positioning, investment in R&D, product and process innovation Improving the positioning in the global automotive chain by manufacturing higher valueadded products is considered of crucial importance, confirming the GVCA predictions. In fact, GCVA analysis identifies four, not mutually exclusive, paths of expansion for subcontracting firms: 1 increasing their x-efficiency 2 strengthening inter-firm connections with partners to build a more consistent and cooperative network than those of rivals 3 improving the quality of their functions along the chain, or moving to higher quality functions (e.g. from production to design) 4 introducing new products or widening the range of products offered. While first two paths seem to be essential requirements for participation in the value chain, but do not warrant per se upgrading in the value chain or ensure against the risk of a future decline, strategies 3 and 4 are key to higher returns and growth. In relation to innovation in particular, Gereffi (1999) points out that the motivation for product innovation primarily comes from global assemblers, the key players in the global value chain, who push supplier firms to meet their demands for more value-added and more sophisticated products. All firms have mentioned their efforts to innovate products and processes, and most of them have succeeded during the 2000–2005 period. On average sampled firms’ investment in R&D is relatively high (between 3% and 5% of the turnover in 2005, with one firm investing as much as 10%).4 Most of the firms cooperate with universities (e.g. with the Politecnico of Turin), carrying out joint research project supported by public funds or EU schemes for innovation. How to cope with the global value chain 245 Nonetheless, most firms have described their products as ‘mature’, and few claimed to have innovative products in their portfolio (Table 4). Among the latter, one company defines itself as a ‘fast follower’, being able to adopt rapidly innovations already on the market, while another produces electromechanical components that are considered ‘niche products with few competitors’. Only one firm reported to have patented its innovation (a new casting technology). Table 4 Products positioning Number of firmsa Innovative 4 Mature, with good profit margins 8 Mature, with narrow profit margins 4 Source: Interviews a Note: Multiple answers are allowed. As to the type of relation with the customers, most firms of the sample have claimed to be involved in relational and market type linkages; however, three companies indicated to be exclusively engaged in co-makership (‘relational’ linkages). This is an interesting aspect, as the more the products are customised and commitments are based on trust, the higher the entry barrier vis-à-vis other global and local competitors. In one case, co-makership is required for the product’s specific requirements (lighting components), while the other two firms supply turn-key systems (for testing engines and automated production systems), with a continuous interaction with the customer, especially during the projecting phase. Two firms declared instead to engage exclusively in ‘market type’ linkages: one of them produces parts almost only for the aftermarket (filters for engines), while the second company supplies die-casted components for engines, following the customers’ specifications. Moreover, according to our interviewees, the involvement in relational (market) linkages seems to be associated with a higher (lower) level of qualification of the firm’s employees. Overall, it is worth mentioning firms’ efforts to increase the share of custom-made products and foster cooperation on projecting and design, as products resulting from cooperative process with the customer usually feature higher innovative content and higher profit margins. Nonetheless it is has to be considered that customers (especially car manufacturers) usually maintain the intellectual property on products developed in cooperation with their suppliers; such a behaviour reduces the incentive of supplier firms to innovate, because of the fear to be expropriated of the surplus coming from their innovation propensity. 4.2.3 Productive internationalisation As showed by Table 5, during the reference period, several firms have followed a ‘cumulative’ internationalisation process (Basile et al., 2003), increasing, at the same time, both their exports and foreign direct investments or partnerships with foreign firms. Firms pursued FDIs through acquisitions and greenfield investments (in China, Poland, Mexico, France and the USA). In other cases, however, firms have preferred to establish joint ventures with local partners (in Mexico, Poland, Brazil, China and France) (Table 5). Exports from Italy Exports from Italy Large Firm9 Firm10 Large Source: Interviews Firm13 Medium Exports only from Italy Firm11 Medium Exports from Italy Firm12 Medium Exports only from Italy Medium Exports from Italy Firm8 Exports from Italy Small Firm7 Firm5 Firm6 Firm4 Sales abroad Commercial FDIs FDIs or JVs for productive activities Branches in the UK 50% JV in China; Greenfield FDI in USA; FDI with the purchase of existing firms (France, Poland, Mexico, Brazil) 50% JV in Brazil (1999); greenfield FDI in Poland (2006) Greenfield FDI in Mexico (2001) Greenfield FDI in France (2006) FDI with the acquisition of a firm in China (2007) Exports from Italy; Technical-commercial agent in Germany base in India (2000) Medium Exports only from Italy Medium Exports from Italy FDI in Poland (2003); JV in Mexico (2005) Large Exports from Italy Technical-commercial FDIs in 19 countries including Brazil, base Argentina, Australia, USA, Canada, Mexico, China, Russia, India, South Africa and a number of European countries (Spain, France, Germany, Poland, Romania, Sweden, Belgium, UK). All takeovers executed Medium Exports only from Italy Small Exports from Italy; Commercial offices in representative in Spain Turkey and Brazil Size Small Arm’s length contracts Future prospects The offices in Turkey and Brazil manage purchases and the local suppliers Plans for a JV in Poland Plans to open a factory and a commercial unit in Eastern Europe in 2008; is also considering the possibility of building a factory in China, shifting some production to Brazil and forming a JV with an Indian partner Plans for an agreement in India for the transfer of know-how Plans to open a production unit in Bulgaria Will consider whether to carry out design and planning abroad Will consider whether to decentralise more production abroad Consolidate current activities Production through suppliers Evaluating the possibility of setting managed by the office in India up a factory in India Table 5 Firm2 Firm3 Firm Firm1 246 C. Castelli, M. Florio and A. Giunta Firms’ size, modes of internationalisation and future prospects How to cope with the global value chain 247 As shown in Figure 3, the main factors determining productive internationalisation are proximity to outlet markets and co-location, followed by the reduction of transport costs, which are all motivations to enhance market access (Figure 3). The decentralisation of production occurs in particular when: (a) products are specialised and cannot be easily supplied from local firms in emerging areas; (b) when products have to be finished by the customer (for example die-casted parts); (c) when transport costs are relevant. These motivations are often considered more relevant than relative advantages deriving from lower labour costs. Nevertheless, some firms – mainly characterised by more labourintensive (e.g. the casting of iron products) or standardised parts – are strongly motivated by efficiency gains deriving from producing in low-cost countries and have chosen to shift part of the production abroad not only because of the customers’ proximity. Figure 3 Determinants of productive internationalisation (see online version for colours) With regard to which functions are transferred abroad, production carried out in the foreign plants has often been defined as ‘similar to the production in Italy’. Most FDIs (or joint ventures) are therefore horizontal rather than vertical5 and are aimed at substituting exports from the district of Turin or expanding the home-based activity. Due to the deverticalisation of the production chain, productive processes tend to be established in other countries according to their technological content and to the degree of automation, rather than according to the different phases of the value chain. The more value-added processes and R&D are still performed in Italy; however, some firms have shifted part of these functions abroad, in particular when the R&D unit has to work in close connection with production. 248 C. Castelli, M. Florio and A. Giunta Alternatively, productive internationalisation can take place through ‘lighter’ modes of internationalisation, i.e. outsourcing part of the production abroad by means of contractual agreements. For example, two firms supplying complete production systems have set up commercial offices to coordinate their local contractual partners. In this way sunk costs are lower, even if there may be other disadvantages in terms of transactions costs, imperfect information and contractual incompleteness (Antras and Helpman, 2004; Barba Navaretti and Venables, 2004). Determinants for the choice of adopting more or less complex forms of internationalisation can be derived from the literature on firms’ heterogeneity, which links firms’ productivity levels to the different degrees of international involvement (Helpman et al., 2004; Greanaway and Kneller, 2007). Size has also to be included among other firms’ characteristics that may exert an influence on different internationalisation modes. 5 Where to operate in the near future? The prospects of Turin supplier firms Evidence from the case study may allow us a certain degree of generalisation and outline under what circumstances suppliers are more likely to maintain their production in the district of origin or whether they may choose to locate (in part or completely) their productive activities abroad, in order to remain competitive (Table 6). In particular, two product characteristics seem to have a particular influence on the firms’ decision to operate in the district of origin or in the new regional poles: the degree of innovation and the relevance of trade costs. Specialised, innovative firms with products characterised by relatively low trade costs may choose to export directly from the Turin area, as car manufacturers source these products ‘globally’, provided that local Turin suppliers can keep the pace of innovation. Conversely, suppliers with innovative products but high trade costs may need to locate near their customers, in order to comply with just-in time requirements. Carmakers are actively triggering their internationalisation process, and supplier firms can successfully compete in the new global districts also with specialised multinational top suppliers. On the other side, suppliers characterised by mature, labour-intensive products and high trade costs are able to survive to global competition only if capable of relocating in one or more regional poles, especially in emerging countries, in order to improve their cost efficiency, besides complying with lean production organisation. Nonetheless, if these firms base their strategy only on price-competitiveness, they are at risk of being crowded out by locally owned suppliers, learning from cooperative relationships with their customers to meet higher quality standards. Finally, firms selling mature products, where the incidence of trade costs is relatively low, could improve their competitiveness by decentralising part of their productive phases in the emerging countries, keeping in the district the higher value-added production, and concentrate, at the same time, on innovating the home-based activities. How to cope with the global value chain Table 6 6 249 Trade costs, products and location of automotive suppliers Innovative products Mature products High Trade Costs Location near the customer in ‘global districts’, where firms compete also with specialised multinational suppliers. Location near the customer, preferably in emerging countries to improve pricecompetitiveness. Risk of being crowded out by locally owned competitors upgrading in the value chain. Low Trade Costs Location in the district of origin, exports directly from the district, as car manufacturers source these products globally. Location of the production in emerging countries to improve pricecompetitiveness; higher value-added phases may be maintained in the district of origin, as car manufacturers source these products globally. Conclusion The geographical dispersion of productive activities near the final markets is leading to the establishment of global industrial districts, where foreign and local suppliers tend to establish plants near the lead carmakers (often in emerging countries), as transport costs and lean production techniques may require proximity to the customer. These ‘new’ districts supply not only local markets, which are often still potential, but are a way to improve cost-efficiency and to serve as export platforms for other areas. Recent figures on the Piedmont Regions’ trade flows of car parts and components, as well as our empirical findings, confirm the involvement of Turin firms which have been able to increase, during the past decade, their participation in the global production chain, pushed by the internationalisation of Fiat Group and the need to diversify their customer’s portfolio. Our case study has illustrated how a group of Turin suppliers – mainly medium-sized firms belonging to the upper level of the pyramid – is acting to increase their involvement in international production processes and upgrade in the value chain, also as a reacting strategy to the crisis of the lead Italian Group which characterised the whole reference period, 2000–2005 (Berta, 2006; Volpato, 2008). Our findings show that companies are pursuing a ‘high road development strategy’. On one side, they have expanded and diversified their customers, pursuing different ways of internationalisation to take part in the global networks and to become less dependent from Fiat Group. Foreign expansion reaches from exporting to producing abroad, in order to supply directly the foreign customers, by means of lighter or more complex forms of internationalisation, according to their products and firms’ characteristics. The drive to further internationalise is strong and is determined more by trade costs and market access factors than by efficiency gains deriving from lower labour costs, the latter being more relevant for firms producing standardised and labour-intensive parts. On the other side, most suppliers engage in innovative activities (product and process) to upgrade in the value chain, also pursuing relational linkages with their customers, in order to raise entry barriers vis-à-vis new competitors. The rationalisation and selection process that took place in the ‘national’ districts during the last decades is set to continue and to intensify at a global level, so that in the long run firms will increasingly have to face the competition of global and local players of every size and, consequently, experience a growing pressure on their profit margins. 250 C. Castelli, M. Florio and A. Giunta This may lead to a further change in the structure of the local system, where the more innovative productions would remain based, while a number of suppliers would continue to shift their activity in the new industrial poles. However, it is worth mentioning that some of the (more or less innovative) firms might be hampered in their ‘follow the client’ strategy by their limited size, financial capacity and other structural factors often described as a weakness of the Italian companies. In particular smaller firms, positioned at the lower end of the supplier pyramid, risk to be driven out of the market. Continuous learning and innovation are therefore crucial for Turin firms’ survival, and competitiveness will be increasingly related to the capacity of meeting higher requirements and non-price factors (innovative content, quality, design, specialisation and customisation). Since most firms of the CCIAAT sample, located in the Turin district, regard their products as ‘mature’, our findings cast some doubts on the ability of local firms to successfully adapt and compete in the new environment. While the local district have acted so far as a catalyser of innovation, the global dimension of the value chain challenges the relatively limited financial and human capital resources of several small-medium enterprises and undermine the probability to survive international competitive pressures. We briefly conclude with some implications for policy from our empirical analysis, which, in the context of the global crisis in the car industry that started in the second half of 2008, are particularly important. Our findings show that the most competitive suppliers seem to be less dependent on the local market and more interested in developing their own international strategy, as Calabrese (2010) shows for the car-designers cluster in Turin. Support for them would require a package that should be tailored to their needs. It is known that public measures, facilitating the flow of export-specific information and supporting diffusion of knowledge about export markets, may have a positive impact on the export performance – the case of French firms is documented in Koenig et al. (2010). A complementary measure could be to incentivise, through financial or fiscal measures, small and medium sized firms to cooperate – for example, by creating consortia – in order to achieve the ‘critical mass’ to support the sunk cost of foreign market penetrations. In a different perspective, investing in local institutions and in those mechanisms that enhance local social capital and knowledge, particularly in an urban context, will help the regeneration of the flexible industrial district. Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to the interviewed firms for their precious cooperation and to Marzio Bianchi for his support with the interviews. We thank the Chamber of Commerce of Turin for allowing the use of their database on automotive suppliers (in particular Silvia De Paoli and Barbara Barazza) and Elena Mazzeo (ICE) for providing data from the ICE-Milan Poliytechnic database Reprint. The authors wish to thank anonymous referees for their comments and useful indications. Moreover, we wish to thank Giorgio Barba Navaretti, Giuseppe Berta and Giuseppe Calabrese for their comments on a previous version of the paper. Financial contribution to CSIL and the University of Milan from the FIRB research project ‘International fragmentation of Italian firms. New organisational models and the role of information technologies’, funded by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research, is gratefully acknowledged. Cristina Castelli is the sole responsible for the expressed opinions, which should not be necessarily considered as the view of ICE. How to cope with the global value chain 251 References Antras, P. and Helpman, E. (2004) ‘Global sourcing’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 112, No. 3, pp.552–580. Arndt, S.W. and Kierzkowsky, H. (2001) Fragmentation. New Production Patterns in the World Economy, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Balcet, G. and Enrietti, A. (2002) ‘The impact of focused globalisation in the Italian automotive industry’, The Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, Vol. 13, Nos. 1/3, pp.97–133. Barba Navaretti, G. and Venables, A. (2004) Multinational Firms in the World Economy, Princeton University Press, Princeton. Basile, R., Giunta, A. and Nugent, J.B. (2003) ‘Foreign expansion by Italian manufacturing firms in the nineties: an ordered probit analysis’, Review of Industrial Organization, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp.1–24. Berta, G. (2006) La Fiat dopo la Fiat. Storia di una crisi. 2004–2005, Mondadori, Milano. Calabrese, G. and Erbetta, F. (2005) ‘Factors of performance in a context of market change: the automotive district of Turin’, in Garibaldo, F. and Badi, A. (Eds): Company Strategies and Organisational Evolution in the Automotive Sector: a World-Wide Perspective, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, pp.213–250. Calabrese G. (2010) ‘Struttura e trasformazione della filiera dello stile dell’auto in Piemonte’, L’Industria, Vol. 2, pp.255–276. Enrietti, A. and Whitford, J. (2005) ‘Surviving the fall of a king: the regional institutional implications of crisis at Fiat Auto’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp.771–795. Ernst, D. (2005) ‘The new mobility of knowledge: digital information systems and global flagship networks’, in Latham, R. and Sassen, S. (Eds): Digital Formations, IT and New Architectures in the Global Realm, Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp.88–116. Feenstra, R. (1998) ‘Integration trade and disintegration of production in the global economy’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp.31–50. Frigant, V. and Lung, Y. (2002) ‘Geographic proximity and supplying relationship in modular production’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp.742–755. Frigant, V. (2007) Between Internationalisation and Proximity: the Internationalisation Process of Automotive First Tier Suppliers, Cahiers du GREThA 13, Université Montesquieu, Bordeaux IV, France. Frigant, V. and Layan, J.B. (2009) ‘Modular production and the new division of labour within Europe: the perspective of French automotive parts suppliers’, European Urban and Regional Studies, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp.11–25. Gereffi, G. (1994) ‘The organization of buyer-driven commodity chains: how US retailers shape overseas production networks’, in Gereffi, G. and Korzeniewicz, M. (Eds): Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism, Greenwood Press, Westport, pp.95–122. Gereffi, G. and Korzeniewicz, M. (1994) Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism, Greenwood Press, Westport. Gereffi, G. (1999) ‘International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain’, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 48, No. 1, pp.37–70. Gereffi, G., Memedovic, O., Sturgeon, T.S. and Van Biesebroeck, J. (2009) ‘Globalisation of the automotive industry: main features and trends’, International Journal of Technological Learning, Innovation and Development, Vol. 2, Nos. 1/2, pp.7–24. Gereffi, G., Sturgeon, T. and Van Biesenbrock, J. (2008) ‘Value chains networks and clusters: reframing the global automotive industry’, Journal of Economic Geography, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp.297–321. 252 C. Castelli, M. Florio and A. Giunta Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C. and Rabellotti, R. (2005) ‘Upgrading in global value chains: lessons from Latin American clusters’, World Development, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp.549–573. Grenaway, D. and Kneller, D. (2007) ‘Firm heterogeneity, exporting and foreign direct investment’, The Economic Journal, Vol. 117, No. 517, pp.F134–F161. Helpman, E., Melitz, M.J. and Yeaple, S.R. (2004) ‘Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms’, American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 1, pp.300–316. Henderson, J., Dicken, P., Hess, M., Coe, N. and Yeung, H. (2002) ‘Global production networks and the analysis of economic development’, Review of International Political Economy, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp.436–464. Hummels, D., Ishii, J. and Kei-Mu, Y. (2001) ‘The nature and growth of vertical specialization in world trade’, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp.75–96. Humphrey, J. and Schmitz, H. (2002) ‘How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters?’, Regional Studies, Vol. 36, No. 9, pp.1017–1027. Humphrey, J. and Memedovic, O. (2003) The Global Automotive Industry Value Chain: What Prospects for Upgrading by Developing Countries, Sectoral Studies Series, UNIDO, Vienna. Available online at: http://www.unido.org/fileadmin/import/11902_June2003_Humphrey PaperGlobalAutomotive.5.pdf Jones, R.W. and Kierzkowski, H. (1990) ‘The role of services in production and international trade: a theoretical framework’, in Jones, R.W. and Krueger, A. (Eds): The Political Economy of International Trade, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, pp.31–48. Jones, R.W. and Kierzkowski, H. (2005) ‘International fragmentation and the new economic geography’, North American Journal of Economics and Finance, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp.1–10. Kaplinsky, R. (2000) Spreading the Gains from Globalisation: What Can Be Learned from Value Chain Analysis?, Working Paper 110, Institute for Development Studies, Sussex University, Brighton. Koenig, P., Mayneris, F. and Poncet, S. (2010) ‘Local exports spillovers in France’, European Economic Review, Vol. 54, pp.622–641. Larsson, A. (2002) ‘The development and regional significance of the automotive industry: supplier parks in Western Europe’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp.767–784. Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (2009) Migliorare le politiche di Ricerca e Innovazione per le Regioni, Ministry of Economic Development, Rome, Italy. Nordås, H.K. (2005) International Production Sharing: a Case for a Coherent Policy Framework, WTO Discussion Paper 11, Geneva, Available online at: http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/ booksp_e/discussion_papers11_e.pdf STEP Ricerche-Camera di Commercio, Industria, Artigianato e Agricoltura di Torino (CCIAAT) (2008) Osservatorio sulla componentistica autoveicolare italiana, CCIAAT, Torino, Italy. Sturgeon, T.J. (2002) ‘Modular production networks: a new American model of industrial organization’, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp.451–496. Sturgeon, T. and Florida, R. (2004) ‘Globalization, deverticalization, and employment in the motor vehicle industry’, in Kenney, M. and Florida, R. (Eds): Locating Global Advantage: Industry Dynamics in the International Economy, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, pp.52–81. Sturgeon, T., Biesebroeck, J.V. and Gereffi, G. (2008) ‘Value chains, networks and clusters: reframing the global automotive industry’, Journal of Economic Geography, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp.297–321. Volpato, G. (2008) Fiat Group Automobiles, Bologna, Il Mulino. How to cope with the global value chain 253 Notes 1 2 3 4 5 The interviews were carried out between June and September 2007, and further evidence was collected and elaborated in 2008–2009. Product innovation means either the introduction of a completely new product (new for the firm) or a significantly improved one. Process innovation means either a radical change in the production process or a significantly improvement in the production process. Internationalisation processes can involve different methods, differing degrees of risk, organisational and relational complexity, and costs. In addition to serving international markets through exports from the country of origin, firms can invest in distribution and commercial penetration abroad. Along with contractual outsourcing these forms are considered ‘light’ modes of internationalisation, while more ‘complex’ forms regard the establishment of productive plants. These findings are well above the ratio of R&D expenditure on value added in the Italian industry, which was equal to 0.78% in 2005 (Ministry of Economic Development, 2009), and above the ratio of R&D expenditure on turnover for the whole automotive sector, which reached 1.5% in 2003 (see http://www.istat.it/dati/dataset/20070329_00/). In literature we find traditionally a distinction between horizontal and vertical FDIs: the former is when the firm replicates in another country the production process that it carries out in the country of origin, usually maintaining in the home country the headquarters and various functions (financial management, R&D, marketing.). Vertical FDIs, on the other hand, involve the geographical separation and dispersion of the different stages of production, by means of the fragmentation of the value chain, and are typically carried out in countries where production costs are lower.

© Copyright 2026