New solution for old problem: how to Articles

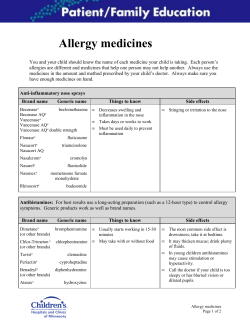

PJ, 01 May, p425-428 28/4/10 10:50 Page 425 Articles New solution for old problem: how to reduce the volume of waste medicines In this article, Liz Breen, Ying Xie and Kuljit Thiaray describe how a reverse logistics framework based on customer relationship management strategy may encourage customer involvement in the reduction of waste medicines in the community, thus lowering risks and saving money I The authors t has been estimated that £8.2 billion is spent each year on prescription drugs in the NHS of which at least £100 million can be attributed to unused or wasted medication.1 On 31 March 2008 there were 10,998 community pharmacies in England providing NHS pharmaceutical services. In the NHS throughout the UK disposal of unwanted medicines is an essential service under community pharmacy contracts. Primary care trusts, which commission these services, monitor compliance. Medicines retrieved from patients cannot be reused and must be disposed of. Close monitoring of returned medicines can be a useful source of information for prescribers. Safety is paramount when broaching pharmaceutical management and storage. Accidents can happen if products fall into the hands of children or individuals who wish to abuse the product or support a grey market for product exchange or sales. Pharmaceuticals that are returned by patients are destined for final disposal and have no legitimate residual value. But the return of these products does have a value: it removes the product from circulation and from the domestic environment, reducing the risk of accidental injury or product abuse; and it provides information that can be used to assess the efficiency of the prescribing process, such as who the prescriber is, the nature of the product and quantity dispensed. Reverse logistics has been defined as “the process of planning, implementing and controlling the efficient, cost-effective flow of raw materials, in process inventory, finished goods and related information from the point of consumption to the point of origin for the purpose of recapturing or creating value or for proper disposal”2 and has attracted attention from academia and industry. The three main drivers of reverse logistics are economics, corporate citizenship and the law.3 Liz Breen, PhD, CMILT-UK, is senior lecturer, Bradford University School of Management. Ying Xie, PhD, is senior lecturer, University of Greenwich Business School. Kuljit Thiaray, MBA, MRPharmS, is senior lecturer, Bradford University School of Pharmacy. Correspondence to: Dr Breen at Bradford University School of Management, Emm Lane, Bradford BD9 4JL (e-mail [email protected]) www.pjonline.com The economic incentive to engage in reverse logistics activities lies in minimising cost and improving profitability by reducing waste, reusing materials, remanufacturing, recycling or product refurbishing.4 Companies that value their own standing as good corporate citizens adopt an approach of sustainable development. They handle the reverse logistics of hazardous materials efficiently and effectively from an environmental and social point of view. Developing an image as a good corporate citizen could open a huge potential market, which eventually makes profit.5 The laws and policies imposed by any jurisdiction dictate the legal obligations of a company to take back the returned products. It is possible that effective reverse logistics could save UK business up to £500 million a year.6 Can it be applied to medicines supply in community pharmacy? A previous study focusing on reducing waste in community pharmacy suggested that closer professional management at the point of dispensing and an understanding of patient experiences can help reduce the amount of unwanted medicines collected by patients.7 The study did not investigate medicines retrieval strategies. A thorough review of the literature indicates that there is little research and practice on medication recycling from a supply-chain management perspective.8 Customer relationship management Community pharmacists sit near the end of the pharmaceutical supply chain close to patients, which means they have a good opportunity to build relationships with them. Patient engagement can be transactional or, if the patient has had a long relationship with a community pharmacy, it can result in something akin to loyalty. It is this element that community pharmacy management needs to secure and build upon to ensure the success and sustainability of a new reverse logistics system. Loyalty can be developed by relationship marketing as opposed to transactional marketing. Customer relationship management includes all activities undertaken by an organisation to identify, select, develop and retain customers.9 The basis of customer relationship management is in knowing customers and this relies heavily on data provided by information management systems. Customer information can be analysed to identify traits and characteristics by which they might be categorised, opening up the possibility of developing individualised approaches. Consideration needs to be given by industry to designing a supply chain that works for both customers and suppliers.10 Social marketing has been proposed as a means of understanding the pharmaceuticals market.11 It is based on the premise that social causes can be marketed like any product. Social marketing can be used to promote socially desirable behaviour, such as recycling, seat-belt use, family planning and AIDS prevention.12 Pharmaceutical recycling would be perceived as a socially acceptable cause and would encourage engagement with a reverse logistics system and positively influence compliance. In community pharmacy, patients are also customers and therefore it could be posited that a blanket approach to customer relationship management is needed rather than a focused approach. As financial return/customer profitability for this venture is not a factor it can therefore be hypothesised that the categorisation of customers could be used for information dissemination purposes. The level and nature of information given to customers could be group-dependent: for some a flier is sufficient to indicate the purpose and action necessary in the reverse logistics system, but others need a one-to-one explanation. A blanket approach, however, would be easier. Managing customers’ perception and loyalty is critical to the success and sustainability of a reverse logistics system, therefore consideration needs to be given to its objective and design.The final design needs to incorporate the essential elements of both managing customers and managing return logistics. Environment, economics and safety The focus on pharmaceuticals in the NHS is mainly on their therapeutic value, but consideration also needs to be given to their impact from an environmental, economic and safety perspective. Studies indicate that the presence of pharmaceutical ingredients in our water supplies and products made using water are potentially harmful to us and our eco-system. A review of related studies indicates that harm can be economic and environmental. The economic costs include the cost of collection and disposal of medicines, the scale of which is indicated by the quantity of medicines returned to PCTs, and costs arising from ineffective prescribing. There is an important safety element, where safe methods of practice can reduce 1 May 2010 The Pharmaceutical Journal (Vol 284) 425 PJ, 01 May, p425-428 28/4/10 10:50 Page 426 Articles the risk of harm, including accidental deaths due to innapropriate medication.Therefore, a properly designed pharmaceutical reverse logistics system for medicines recycling must take account of all of these factors. In order to introduce an integrative customer relationship management strategy to facilitate effective reverse logistics in community pharmacy, the following three objectives need to be realised: Recycling centre Management information system Medicines use review ▼ General practice ■ An understanding of customer roles in the reverse logistics system in community pharmacy ■ Identification of the drivers for increasing customer compliance in returning unused medicines to community pharmacies ■ Identification of how to support customer involvement Reverse logistics ▲ ▲ Forward logistics Information flow Figure 1: A proposed pharmaceutical recycling system for community pharmacy have been wasted across a single health authority, if figures produced from a study of four pharmacies over a two-month period are representative of overall performance.14 The findings from a waste audit conducted by Rowlands Pharmacy (personal communication) indicated that when extrapolated, the total cost of returned medicines for a year would have been £4,690,428.The results indicated that the main reason for customers returning a medicine was that they had stopped taking it (49 per cent of returned items). So what role can customers play in reducing waste in this system? Unlike the traditional model of recycling, where goods can be recovered and reused, ■ Access to recycling services ■ Environmental knowledge ■ Recycling experience ■ Vouchers given for the return of medicines ■ Exchange for other medicines ▲ ▲ Financial incentive Concern about the hazard posed to children or vulnerable people by medicines left in households ▲ ▲ Individual circumstances Concern about potential harm to the environment posed by disposal of medicines ▲ ▲ Health and safety Reduced production costs or packaging costs ▲ ▲ Environmental considerations Positive impact on community and society of recycling medicines ▲ Economic concerns ■ Laws governing disposal of household pharmaceutical waste ■ National regulations on the disposal of prescription medicines ▲ Corporate citizenship pharmaceutical products take a different recycling pathway, that is, to final disposal by a third party. Individual customers can make a strong contribution by returning medicines. All customers are different, so there is no single definitive skill set or expertise that community pharmacies can draw on to design their reverse logistics systems. The role of the patient in the management of pharmaceutical waste has been a passive one in some respects, as it is controlled by professionals. Under the reverse logistics system proposed in Figure 1, where customers return the medicines to community pharmacies, GPs or recycling centres via different channels, there a need for active participation ▲ Legal framework ▲ ▲ Operational Text, telephone call, e-mail ▲ Drivers ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ Perceptional Customer Community pharmacy ▲ ▲ Roles of customers Previous research has examined industrial reverse logistics practice in business-to-business and business-to-customer relationships (including pharmaceutical wholesalers and manufacturers) to determine the financial and operational impact of customer non-compliance in returning equipment to its source.13 The study found that the efficacy of reverse logistics can be undermined by a lack of customer compliance, with business-to-business losses of up to £140 million. Non-compliance of this nature can carry a direct cost for manufacturers and distributors. It was advocated that suppliers in industry need to acknowledge this issue and manage their reverse logistics more effectively. While focusing on efficiencies and reducing waste in the NHS, another study concluded that approximately £800,000 could ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ Figure 2: Drivers of customer compliance (adapted from De Brito et al3) 426 The Pharmaceutical Journal (Vol 284) 1 May 2010 www.pjonline.com PJ, 01 May, p425-428 28/4/10 10:50 Page 427 Articles and decision-making about product returns. The return process can take the form of a single, clean-sweep event, whereby individuals send their unwanted medicines to a recycling centre — successfully implemented in Maine15 — or via a drop-box in GP surgeries or community pharmacies. The outcomes of the audit at Rowlands Pharmacy led the chain to recommend that patients should be asked why they return medicines and to instigate a medicines use review (MUR). GPs should also be consulted about the patients involved, and an efficient management information system is proposed to help GPs to monitor patients’ progress and remind them, by text, telephone call or e-mail, to return unwanted medicines. In the management information system, patients’ consultation and personal details will be recorded, together with the MUR results. Similar conclusions were reached in other studies.16 Communication and encouragement on customer compliance Internet, media (TV and newspapers), pharmacy or NHS leaflets Customer relationship management strategy Customer support Customer enquiries Customer service Customer feedback Product management Product life cycle management Reverse logistics network for returned drugs Product design and packaging GP’s prescription period Inventory management for returned drugs Return channels Medicines use review Drivers of customer compliance Economic concerns, individual circumstances, health and safety, citizenship, legal framework Figure 3: Components of an effective reverse logistics system Drivers of customer compliance New guidelines have been published outlining the need to improve patient involvement in decisions about their medicines and thus promote adherence.17 The pharmaceutical reverse logistics systems should be designed in such a way that customer compliance is enhanced through customer recycling behaviour. Customer recycling behaviour is driven by various factors, and it is necessary to develop a model (Figure 2) for better understanding of these drivers before constructing the pharmaceutical reverse logistics system. The drivers of generic reverse logistics system are corporate citizenship, economic concerns and the legal framework,3 which are also identified as the drivers of customer compliance in pharmaceutical reverse logistics system, as shown in Figure 2. In addition, environmental considerations, health and safety, individual circumstances and financial incentives are identified as the other four drivers to customer compliance. The legal framework, corporate citizenship, economic concerns, environmental considerations, and health and safety are classified as perceptional drivers, while individual circumstances and financial incentives represent conventional operational drivers. The environmental, economic and safety considerations have been justified above. Legislation governing the disposal of household pharmaceutical waste can impose a legal obligation on customers to return unused medicines. In Jefferson County, Wisconsin, prescription medicines have to be be separated from household pharmaceutical waste when being returned, and the medicines accumulated from more than one source have to be disposed of according to national regulations.18 Corporate citizenship requires customers to handle pharmaceutical waste from an environmental and social point of view. Having the initial motivation for environmental protection, customers recycle unused medicines properly. If individual customers have positive environmental attitudes and active concerns www.pjonline.com about health and safety, then higher levels of recycling behaviour should happen. Considering the hazards that out-of-date and unused medicines pose to children and other vulnerable people, customers will have enhanced compliance in recycling the excess medicines in households to reduce the risks. Customers should not need training and education to perform their role as reverse logistics agents (delivering part of the service on behalf of the pharmacy) because they cannot be expected to separate out hazardous waste.19 The responsibility for decision-making on medicines resides with pharmacy staff so all patients should be advised to return unused medicines. Supporting customer involvement To make the reverse logistics system operate properly, individual circumstances have to be taken into account when encouraging customer compliance. From a customer’s perspective, individual circumstances refer to: ■ Access to recycling services via the medicines retailer, the manufacturer, or other providers: maximised recycling provision should result in enhanced customer compliance. ■ Socio-demographic variables, such as age and knowledge: individuals with greater environmental consciousness and more knowledge on how and what to recycle should have enhanced compliance. ■ Recycling experiences: positive experiences can promote enhanced customer compliance. It should be noted that incentive schemes can underpin and stimulate compliance, for example, customers could be rewarded, by giving them vouchers for returning unused medicines, or perhaps exchanging them for other medicines. The same logic can be applied to internal reverse logistics practice. In 2005, Coventry PCT introduced a local enhanced service called the “not dispensed” scheme.This service allowed pharmacists at the time of dispensing a prescription to ensure the patient needed all the medicines. For every “not dispensed” noted on the prescription an extra fee could be claimed from the PCT.20 The same practice has been adopted elsewhere. Pharmacists in the Republic of Ireland, for example, can claim a fee of £1.87 for not dispensing a prescription after the “exercise of professional judgement”.21 Some might believe this to be a regressive action since it does not tackle the root cause: ineffective prescribing.They might argue that the action taken by pharmacists in this example masks the problem and incurs a double cost — the cost of prescribing more medicines that may be unnecessary and not used, and the cost of rewarding pharmacists. System framework Based on the drivers identified in Figure 2, a framework has been developed to provide key components to be considere in the design of a pharmaceutical reverse logistics system (Figure 3). Considering the unique characteristics of the medicines, five central areas are recommended in designing a reverse logistics system for community pharmacy: 1. Customer advice and support Customer compliance in returning unused medicines should be advocated and stimulated via different communication channels, such as the internet, broadcast and print media, and pharmacy or NHS leaflets. The need for more visual information such as recycling logos and alerts such as “Keep out of reach of children” should be considered to maximise the usefulness of the packaging and raise customer awareness of the product they are handling. 2. Customer relationship management A comprehensive customer relationship management programme based on the reverse logistics system can have a significant 1 May 2010 The Pharmaceutical Journal (Vol 284) 427 PJ, 01 May, p425-428 28/4/10 10:50 Page 428 Articles impact on increasing customer compliance. It is needed to provide customer support and service, answer customer enquiries, and take customer feedback when handling the returned medication. A sustainable pharmaceutical supply chain cannot succeed without the contribution of its customers. Customers are already asked to return medicines, but no effort is made to encourage or manage their involvement. Customer involvement must be prompted and supported through the use of information systems and technology. Indeed, findings from a Swedish study indicate that a customer-centric approach — which a reverse logistics system should be — should be devised.22 Customers have more power collectively than as individuals,23 however an individual approach to managing the customer could be facilitated with better technological resources. From an operational point of view the more standardised the approach the better, as it would require less resources and funding. 3. Product management Medicines should be designed to facilitate the returns process: ■ The design and packaging should facilitate carriage and return. ■ GPs should write prescriptions for shorter periods. Shorter prescription periods (seven to 14 days) have been successfully trialed in Canada.24 ■ Reviews of the use of dispensed medicines are regularly conducted by GPs and community pharmacies as part of their NHS contract obligations. These should help to reduce unnecessary medicines in circulation and promote informed decisions about pack sizes and synchronisation, as advised by the National Prescribing Centre. ■ Allowing customers to collect repeat prescribed medicines from community pharmacies without consulting a GP each time allows pharmacists to ensure patients are taking their medicines correctly and find out if they are experiencing any side effects. Such a service reduces the amount of medicines in circulation. 4. Effective inventory management Returned medicines need to be properly classified, stored and disposed of. Therefore, proper inventory management should be in place in the reverse logistics system. 5. Drivers of customer compliance Enhanced customer compliance, spurred on by the drivers of environmental concerns, individual circumstances, health and safety, corporate citizenship and legislation, will help ensure the success of a pharmacy reverse logistics system. Conclusion The aims and objectives of any reverse logistics system need to be realistic.While the return and recycling of pharmaceuticals is desirable in reducing waste and encouraging efficiencies in prescribing, especially in the light of the economic downturn, where the NHS is facing a reduction of between £8 billion and £10 billion in the three years from 2011,25 it is not a critical objective for the average household. UK families have more pressing issues. This being the case, there needs to be a concerted effort for the reverse logistics agenda for pharmaceuticals to plug into personal agendas to ensure that returns actually take place. Consideration needs to be given to the breadth of this issue. Ultimately, the focus of this article is the reverse logistics system. If well designed it could provide a safer, medicine-free domestic environment and help lead to more effective prescribing, thereby generat- ing cost savings.A broad approach needs to be adopted in relation to medicines design, manufacture, distribution and disposal. We cannot forget that there is a cost to designing and delivering an effective reverse logistics system. Pharmacies encourage patients to return medicines, but do not reward them for doing so. Considering that costs are incurred in designing and publicising such activities and there are charges for final disposal, the purpose of the reverse logistics system for pharmaceuticals in community pharmacy could be questioned. Not everything servicerelated can be costed.The potential savings derived from prescription data and reduction of potential hazards or accidents are valuable considerations. In summary, an effective reverse logistics system can influence the following: ■ The return of potentially hazardous materials to pharmacies, reducing the risk of accidental injury, misuse or abuse ■ Awareness and social consciousness of medicines recycling ■ Patient engagement with the NHS ■ Improved prescribing practice whereby patients are prescribed medicines more frequently, ensuring more contact time with health professionals ■ Information gathering, by providing valuable information, which can promote effectiveness in practice and efficiencies for the NHS ■ Improved collaboration among medicines supply chain stakeholders The success of a reverse logistics system lies in its execution and this is dependent on the approach taken by the NHS to managing customer involvement and behaviour. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to Rowlands Pharmacy for permitting access to and use of its waste audit results for 2009. References 1 BBC News. Call to curb rising NHS drug bill. 2008. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/7190267.stm (accessed 8 April 2010). 2 Rogers DS, Tibben-Lembke RS. Going backwards: reverse logistics trends and practices. Reno, NV: Reverse Logistics Executive Council, 1998. Available at www.rlec.org/reverse.pdf (accessed 8 April 2010). 3 De Brito MP, Dekker R, Flapper SDP. Reverse logistics: a review of case studies, In: Fleischmann, Bernhard, Klose, Andreas (editors). Distribution logistics advanced solutions to practical problems. Series: Lecture notes in economics and mathematical systems. Berlin: SpringerVerlag, 2004;544. 4 Stock J, Speh T, Shear H. Many happy (product) returns. Harvard Business Review 2002;80:16. 5 Krumwiede DW, Sheu C. A model for reverse logistics entry by third-party providers. OMEGA: International Journal of Management Science 2002;30:325–33. 6 Oliynik D. The elephant in the room. Logistics and Transport Focus 2009;11:33–36. 7 Jesson J, Pocock R, Wilson K. Reducing waste in community pharmacy, Primary Health Care Research and Development 2005;6:117–24. 8 Ritchie L, Burnes B, Whittle P, Hey R. The benefits of reverse logistics: the case of the Manchester Royal Infirmary Pharmacy. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 2000;5:226–33. 9 Kasper H, van Helsdingen P, Gabbott M. Services marketing management. A strategic perspective (2nd ed).Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2006;145. 10 Collin J, Eloranta E, Holmström J. How to design the right supply chains for your customers, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 2009;14:411–7. 11 Holdford D. Understanding the dynamics of the pharmaceutical market using a social marketing framework. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2005;22:388–96. 12 Fox K, Kotler P. The marketing of social causes: the first ten years. Journal of Marketing 1980;44:24. 428 The Pharmaceutical Journal (Vol 284) 1 May 2010 13 Breen L. Give me back my empties or else! A preliminary analysis of customer compliance in reverse logistics practices (UK). Management Research News 2006;29:532–51. 14 Braybrook S, John DN, Leong K. A survey of why medicines are returned to pharmacies. Pharmaceutical Journal 1999;263(Suppl):R30. 15 Safe Medicine Disposal for ME Programme. 2009. Available at: www.safemeddisposal.com/ Research.php (accessed 8 April 2010). 16 Boivin M. The Cost of Medication Waste. Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal. May. 1997: 32-39. 17 National Institute for Clinical Effectiveness. Clinical guidelines CG76 Medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. London: NICE, 2009. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG76 (accessed 8 April 2010). 18 Grabow S, Brachman S. Addressing pharmaceutical waste in Jefferson County — planned response. Proceedings report of educational programs and workshop results. 2007. 19 European proposals provide opportunity to solve practical issues on hazardous waste. Pharmaceutical Journal 2007;278:42. 20 Coventry Teaching PCT. Prescribing waste. 23 January 2007. Available at: www.coventrypct.nhs.uk/ documents/general/2007121152449_prescribing_waste.pdf (accessed 8 April 2010). 21 At least 523 tonnes of medicines wasted each year. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2004;272:145. 22 Osarenkhoe A. and Bennani AE. An exploratory study of implementation of customer relationship management strategy. Business Process Management 2007;13:139–64. 23 Anderson H, Brodin MH. The consumer’s changing role: the case of recycling. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 2005;16:77–86. 24 Paterson JM, Anderson GM. Trial prescriptions to reduce drugs wastage: results from a Canadian program and a community demonstration project. American Journal of Managed Care 2002;8:151–8. 25 NHS Confederation. Dealing with the downturn. The greatest ever leadership challenge for the NHS? Available at: www.nhsconfed.org/leadership (accessed: 8 April 2010). www.pjonline.com

© Copyright 2026