A Paper Indiana Bible College

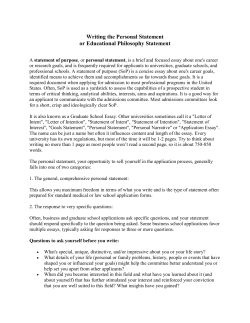

How to Write an A Paper Provided by Indiana Bible College Distance Learning This paper includes suggestions to help the Distance Learning students produce a college level paper for their studies. This paper is by no means exhaustive, but is provided is provided as an aid to the students studies for Distance Learning. Assignment Format for This Course MLA standards are required for your essays. MLA guidelines can be found in college handbooks, which are available in most bookstores or, online at www.mla.org (A new favorite college handbook is Universal Keys for Writers by Ann Raimes, Houghton Mifflin publisher. ISBN 0-618-11288-X This handbook is available in hardback, or spiral version. Essays must be neatly written, double spaced, spaced and stapled (no paper clips) Regular 12 point font, Times Roman, (no italics, or cursive) No cover sheet necessary. In most college English and humanities courses, you will be expected to follow the conventions of documentation and format recommended by Modern Language Association (MLA). You need to document the sources of your information, not only in research papers but also in shorter essays in which you mention just a few books, articles, or other sources to illustrate a point or support your case. When you include any references to an outside source in an academic essay, you need to let your readers know exact details about the source in order for them to identify whose words or ideas you are using and can refer to the source if necessary. Source verification is also important in publishing. Several styles exist for properly setting up essays. The most popular are MLA, APA, and Chicago style. APA style is often used for science courses such as psychology, and sociology. Chicago is the preferred style of book publishers, but MLA has the largest writing audience. Modern Language Association (MLA) is the style most commonly used to document sources in the humanities. Numerous MLA references are available in bookstores, libraries and on the internet (www.mla.org), but for the purposes of Distance Learning we will establish these rules (sample included on the next page). One inch margins on all sides 12 point font (preferably New Times Roman) Double space throughout Indent a new paragraph five spaces or approx ½” Title: centered, not underlined The writer’s last name and page number on every page (usually top right) The top left of the first page should have; Writer’s name Instructor’s name (optional) Class or course title with assignment title Date Jonathan Smith Instructor Kenny Noble Creative Writing Assignment One August 11, 2008 Vegetarianism: Limiting or Healthful? On a breezy spring day in 1999, Brandy Jones made a choice that would change the way she lived. On that day, Brandy revealed in an interview, she woke up early as usual to run the two-mile loop with her friend. For weeks she had been feeling low. Her allergies had been acting up, and her energy level seemed below that of her friends. She was eating a balanced diet, supplemented with the proper vitamins, and she was getting plenty of rest. But even though she was taking care of her body better than most of her friends, she knew she wasn’t at her optimum level. That is when she read the book, Eating for a Better Life. According to the author “what you eat more than anything else is what determines how you feel” (Wong 98). Brandy claims if it wasn’t for this book she wouldn’t have made it to her eightieth birthday. What is Good Writing? A list of good writing attributes may vary from person to person, but each list will probably contain the same basics. At a minimum good writing requires the author to be; Of course, this is not a complete list of good writing attributes. In addition most would agree that it is important to use sensory appeal and to be aware of pacing and rhythm. The list could go on for several pages. Be Correct Misuse of a word or a fact destroys the writer’s credibility. For example, if the writer of an essay writes about a medical situation, then it is the author’s responsibility to bare the burden of proof. If the author mentions a real life celebrity in an essay, and that celebrity is portrayed with certain habits, or implied to have certain convictions then it is important that that same celebrity does have these conviction. There may be a reader who knows if your facts are wrong. They will not only tell others of your mistake, but what is worse is that they may never read your work again. Tip: If your story involves a certain trade let a master of that profession read your work for correctness. Usually, they are delighted that you have asked them. It should go without saying that you should be considerate of their schedule, and be grateful for their time . Be Consistent Consistency of style means that you follow your stylebook; a manual containing rules of punctuation, capitalization, abbreviations, and numerals. Do not use courtesy titles with some people and last names only with others. Do not abbreviate states in one place and write them out in others. A mechanic that does not know the names of the tools he or she uses lacks creditability—so does a writer who does not know how to punctuate. Do yourself a favor and purchase a good stylebook. It will give you years of service for a small price. Be Concise Concise does not mean short. Being concise means saying what needs to be said in as few words as possible. Instead of “His voice went booming through the quiet morning woods,” Write “His voice boomed. . . . “ Instead of “The president lowered his head and disappeared into the airplane,” Write “The president ducked into the airplane.” Be Clear The ability to express oneself clearly is crucial in all fields of work. (Except, perhaps, that some lawyers obscure for obscurity’s sake.) Clarity in writing is the result of using words precisely, being grammatically correct, and relying on simplified sentences. Clarity is impossible without precision. A rose by any other name might smell as sweet, but call it by any other name and you will misinform those who do not know any better. Another example; A pin oak is not the same tree as a red oak (the pin oak trees in my front yard keep their leaves most of the winter, while the red oak trees nearby shed their leaves in the fall. Use the precise word you mean. Few if any words have a true synonym. Be Coherent Present information in a logical sequence, whether it is a time sequence or spatial sequence. Use transitions when appropriate, but beware of sticking transitions in for transitions sake. The Writing Process W hen you begin a writing assignment, do not begin by visualizing the final product— three to ten pages, typed, corrected, paginated, and stapled. You will just feel intimidated by all the work required to produce a finished product. Instead, think about more immediate goals and smaller steps you can take to complete a finished paper. Writing is a process that moves through stages almost anyone can manage. There are many ways to go about the writing process, but the most common method that has been tried and proven for many years is the stage process. There are a few variations on the stage process but for the purpose of this course we will use the following, which I call the PDREP Prewriting, Drafting, Revision, Editing, Presenting Many successful authors describe themselves as shifting freely between the stages of the writing process as they work on a writing project. Some writers delay all their major revisions until they have a first draft; others revise as they work, preferring to compose a paper, sentence by sentence. Some writers may repeat steps in the process several times before they produced a finished piece. They also adjust their composing process to the job they are doing. Writing should not be thought of as a lockstep march from outlining to editing. Instead it is a dynamic, free-flowing process that writers adapt to their needs. Almost everything in your life prepares you for writing: things that have happened in your family or on your job, your hobbies, your experiences in sports, your relationships with friends, and your experience as a citizen in a complex society. You have ideas to explore, opinions to examine, and beliefs to explain and defend. Your memory is crammed with material that you can draw on to develop your articles. All this adds up to such a rich stock of resources that you should not run yourself down by saying, “I have nothing to write about.” Of course you do! You have an abundance of experience that will interest other people. In addition, the more alert you become to the world around you the more material you will have to work with. An important rule to remember in writing is that your goal is to educate readers and hold their interest. Even fiction stories offer a vast source of knowledge for the reader. Nearly all fiction writers do a tremendous amount of research to support the novels they write. For example, Louis L’amour, an American author who wrote over 80 western novels was considered an outstanding writer by many readers because of the accuracy of his stories. If the story mentioned a cowboy camping at the fork of a river between two valleys in a certain county, then most likely the reader could travel to that exact spot and find that fork of the river between the two valleys. One of the benefits of research is that it reveals so many ideas to write about. Therefore, research should not be looked upon as drudgery in the writing process. Research can be exciting and often it is research that separates the excellent articles from the mediocre. An excellent place to start academic research is to visit university web sites. Many university web sites allow access to databases. Also, most state libraries offer online databases to research. Prewriting Prewriting has different forms and styles, but the most common is free writing. Free writing is simply sitting down to write and getting words on paper. Your thoughts may ramble and you may write ideas that you know you will never use, but still you keep writing until you have some acceptable quantity (not quality). Grammar, style, mechanics as well as every other writing element that may inhibit your thought process is disregarded. Free writing is letting the writing juices flow where ever they take you. Later you can decide what to keep and what to scratch. Often free writing will give you ideas you had not thought of previously. This prewriting stage is not the draft—not even the rough draft, it is just the beginning. It is a lot like moving into new territory and looking around first to see where you want to start. Another type of prewriting is clustering. Some call it (the concept map, the bubble map, the vein map, or the idea map). This too is a type of brainstorming for ideas, and it is commonly used among executives and in the business world. Many writers use clustering to start and organize the flow of ideas. For a story to work, it has to engage with what we already know. What images and feelings does a story activate in the reader’s mind? What associations with a central term does the reader bring to the story? Clustering is a prewriting technique that lets you explore a network of images, memories, or associations. With strands of ideas branching out from a central stimulus word—from this word, you can follow the different chains of associations the central idea brings into play. The idea is to sketch freely, spontaneously, what a key word or a key term brings to mind. Clustering is a stimulus technique of double value to you if you are the kind of writer who might otherwise be staring at a blank sheet or screen. First, you call up from the memory bank of your mind much material that might potentially be relevant to a topic. You access thoughts and feelings; you map graphically what you are inclined to think and feel on a topic. At the same time, however, a pattern takes shape. You begin to see possible connections and relations. Some sorting, some shaping is going on at the same time that you are taking stock of relevant memories associations, and overtones. Again, you simply start with one main idea in the center of your paper and draw lines out from the topic and write down a related topic. From that second topic extension (or node) you draw another line or two and add related topics. Some call this style webbing, because it resembles a spider web when finished. Some may feel this technique is elementary because they used it in junior high, but many successful writers use this method. Drafting The draft is the first roughed out areas of the paper. Later, you may move entire paragraphs or even several paragraphs, but for now you are trying to establish an order. Most good authors write several drafts, each draft improving on the former draft. It is important to be aware that in the draft stage the writer is not devoting a lot of attention to the mechanics. That will come later. It is not necessary to worry over the grammar of a paragraph that later may be completely tossed out. Revising Revising is the most overlooked stage of the writing process. Revising is taking the draft a step farther and adding shape to the project. Always remember that writers are made not born. You have to learn to write and the revision process is the writing stage that separates the “wanna be” from the pro’s. This is true because many cannot accept the fact that an article must be revised over and over. Many authors claim they are not good writers. Instead they say they are good revisers. The author examines the logical sequence, the paragraph coherence. Every thought in the article must relate to the thought before and after it. If it does not, this is the stage to fix it. The main topic must be supported by subtopics. The article or story must have a summary and a conclusion (not the same thing). * Tip: The best way to revise a story or article is to put it away for several days and let it marinate. When the author has spent a lot of time on a piece, he or she practically has it memorized. Unfortunately, after the author has read the piece numerous times it is difficult to see the mistakes and typos because it is all inside the mind and at times the author is skimming over lines without realizing it. After it is put away for a few days it starts to be forgotten. Then it can be pulled out and read more objectively. You will see things you never noticed a few days ago. Some stories will need to be revised only a few times. Perhaps a lot of the revising has been done in the mind before writing, or between revisions. Or perhaps you are fortunate to have one of those God-given miraculous moments when things just flow together like you want. When this happens realize that it is a special blessing and never forget it. Write it in your journal so that you can be reminded and encouraged by it on the discouraging moments when you want to just give it all up. Unfortunately most pieces will need revised many times. It is not uncommon for an author to revise 10 to 20 times. Ernest Hemingway reported that he revised the ending of one story 32 different times. But always keep in mind that each revision makes it a better story. Editing Editing is the final manicure. After all else is completed and all the dirty work is accomplished the meticulous details are examined. Grammar, spelling, punctuation, typos are the purpose of this stage. Why spend time editing a paragraph that you may later cut from your paper. Work on your structure first, then fix the details. If you are fortunate enough to have a friend that will read your writing at this stage you are truly blessed. Compliments are nice, but only constructive criticism will help you grow as a writer. Keep in mind that you are the author and this is your article not someone else’s. If you do not like the responses you get from it, then you have the option to disregard them. It is your baby—you brought it into the world and only you can take it out of the world. No one can give you perfect advice all the time. However, if several people give the same comments about your story, then you will benefit to listen to their advice. Presenting This is the easy part. Presenting is sending the article out for publication, or turning it in to the instructor. Note: Be aware that many authors have the attitude that a story is never finished. Some famous authors have been known to continue to revise their story even after the work has been published. I know of one author who was seen with one of his paperback novels in hand—he was still revising. Many writing assignments allow the student freedom to choose personal topics and style. Writing is usually a higher quality when students write about something that interests them. Therefore, write about things that interest you. Choose a topic that is fun and interesting, or choose a topic that you want to learn about. Remember that sometimes adding a little humor, or focusing on overlooked details make a huge difference in the quality of the essay. Collaboration is an effective strategy, which nearly always results in a better paper. Once you have finished your paper ask a friend to read your essay and offer constructive criticism. Keep in mind that you are not obligated to accept their comments, after all their writing skills may be poorer than your own, but they are readers of the English language and therefore may be able to offer good advice. Y ou always have to adjust your writing to your audience. First, you have to understand who that reading audience will be. Obviously, the difference between third graders and college students make audience recognition and adaptation seem simple. It is not. Even sophisticated writers sometimes misjudge their readers, offering them material they cannot or will not digest. Sometimes writers have to deal with multiple and possible conflicting audiences; men and women; young and middle aged and on and on. So you need to analyze your audience almost every time you write. Visualize the people to whom you are writing. Draw a mental picture of your readers as a group, or perhaps choose on individual who you think typifies that audience. Keep that group picture or that individual portrait in mind as you write. In this way you will learn to direct your work to somebody. “Somebody” of course, can be a readership of one person, a small group of people, or a larger group of people. Occasionally, you may want to defer considerations of audience until you get a second draft. Analyze the characteristics of your readers. What are their values and attitudes? What reasons might they have for reading your work? How much do they already know about your subject? What do they believe about your subject? What questions are they likely to have about your subject? How best can you inform, persuade, or otherwise appeal to them? Obviously, learning to analyze an audience skillfully takes time and practice. But developing a sense of audience is critical to any writer. To help you think about your readers, we have developed an audience worksheet that you can apply to many writing situations. Making Your Writing Clearer Show don’t tell Make your writing visual Use action sentences and active verbs Be concrete and specific Write in the active not passive voice Replace adjectives and adverbs with better nouns and verbs In writing, first prize always goes to clarity. If your readers cannot understand what you mean, they are not likely to admire your smooth writing or fresh ideas. If you want to learn to write clearly, you have to care about results and be willing to work to get them. There are no quick fixes. But you can reach your goals by developing habits that, over time, virtually guarantee impressive results. Can you be more specific. Among the most frequent comments instructors make on student papers are “Your using too many generalizations that do not give enough facts—you need to narrow your focus and give specific details,” and “Your language is too vague and abstract— let’s have some concrete examples.” To make your writing more specific, learn to combine abstract and concrete language. Writers who use a great deal of abstract language are often hard to understand. When their writing is weighted down with nouns such as accountability, confrontation, realization, ambiguity, and misapprehension, we begin to have trouble because we can’t see anything. Such abstractions transmit no images to our brains and gives us no examples with which to identify; therefore it takes longer for us to read a passage and remember it. That is why you have so much trouble with some of the material you have to read for your courses and with documents such as insurance policies and legal descriptions. The best policy is the old humorous “Keep It Simple Stupid” (KISS). Original The propensity of overweight people to gain extra adipose tissue at holiday time is due to two factors: greater susceptibility and responsiveness to food stimuli and poor compensatory regulation of food intake. Such individuals seek justification for their behavior by citing the pressures of hospitality and the tastiness of the food. Revision Overweight people gain weight at holidays for two reasons: they like to eat more than average people do, and they have less self control. They excuse their overeating by saying their hosts urge them to eat and, besides, the food is too good to refuse. Which version is clearer? You decide. Wordiness Prune Words to highlight the main idea Trim excess words and phrases Streamline and tighten bureaucratic prose Most readers are impatient with writers who use far more words than they need to express ideas. So if your writing is wordy, work on ways to make it tighter. As you revise to get rid of unnecessary words, your writing will become more forceful and more professional. Wait until you have a first draft before you start trimming your writing. Many writers write rambling prose in their first versions of a paper because they want to establish their ideas before pruning and shaping them. This is okay. If you start to worry about wordiness too soon, you might lose momentum. Be reassured that it is better to have too much than too little to start with—you can always cut. Why write When you could write put the emphasis on emphasize have an understanding of understand make a comparison compare is reflective of reflects give permission to allow in opposition to oppose When you cut verb phrases and focus on the action, you will get an added bonus. You are more likely to match subjects and verbs correctly because you have trimmed out intervening words that camouflage the subject. Eliminate redundant expressions Why write When you could write trading activity was heavy trading was heavy the papers were of a confidential nature the papers were confidential obstetrics is her area of specialization her specialty is obstetrics the banner was blue in color the banner was blue the pool was round in shape the pool was round Helpful Hints Cut down on expletives Expletives are short expressions such as “it was” and “there are” that function like starting clocks for pushing off into a sentence. Examples. It was a dark and stormy night. There were five of us huddled in the room. There are a great number of gopher holes on the golf course. It is an unusual opportunity for the students to learn a new language. Habitually using “there is” and “there are” at the beginning of sentences or clauses can give your writing a tedious, singsong rhythm and make it sound amateurish and flat. Sometimes you cannot avoid using expletives—“it is cold today”—but more often, such expressions just delay getting to your subject. Why write When you could write there is a desire for we want there are several reasons for for several reasons there was an expectation of they expected it is obvious that obviously it is clear that clearly it is to be hoped we hope Avoid generic titles. Although you may not hit on the right title until late in the process of writing your paper, remember that the title will be the first thing to strike your reader. Titles should not be perfunctory and interchangeable—good perhaps for filing the paper under the author’s name or the name of the story, but not enough to hook the reader into reading your essay. A good title in informative (it helps map the territory), but it should also be beckoning. Your title should be specific and attractive enough to invite the reader. It need not be a “grabber,” but it should be alive. It should suggest a top; a point of view, a program, a style. As the Head and Shoulders ad says, “You never get a second chance to make a first impression.” A good title draws attention to the writer’s skills; it signifies “Quality Paper Ahead.” Generally good titles either display cleverness or show direction. Allusions Usually the most effective allusion titles are not direct borrowings but slightly altered one. Red, White and New (Douglas Looney, Sports Illustrated) Just Say Perot (Sidney Blumenthal, The New Republic.) Puns 28 Pass Stiff Embalming course (Boston Back Bay Leader). Kangaroo Meat Suspected Here; Officials Jumpy (New York World Telegram and Sun). Rhyme Rhyme is not just for poetry, it can enliven prose as well. Best Meals, Best Deal (Consumer Reports). Alliteration It can be used for literature or used for generic brand (Cost Cutter), songs (“Crimson and clover”), and even super heroes (Peter Parker, alias Spiderman). Titles appear in every magazine from Reader’s Digest (“Terror in a town Pool”) to Cats (“Feeding the Family Feline”). Paradox Paradoxical titles work particularly well with an unexpected topic or information. Home Sweet Toxic Home (Money). The Day My Silent Brother Spoke (Reader’s Digest). Depending on the point of view (Direction) Safe Driving Begins with Air Bags The Overrated Air Bag Air Bag Arguments Full of Hot Air Combination Killer Cows---paradox and alliteration (Field and Stream) Just Make ‘Em, Don’t Bake ‘Em: Easy no-Fuss Desserts—rhyme and direction. Transitions are to writing what rhythm is to music. Transitions help the reader keep their place—they signal where the reader is located in the story. Sentences may be correct, clear, effective, and appropriate, and yet be neither clear nor effective when they are put together in a paragraph. If the order of the sentences within the paragraph is fully logical, then any lack of clearness probably is due to faulty transition. Transition means passing from one place, state, or position to another, and evidence of transition consists of linking or bridging devices. As applied to writing, there are three degrees of transition; between paragraphs, within the sentence, and between sentences. Between paragraphs: When we say that a theme should be coherent, we mean in part that the paragraphs should be properly tied together. If the order of the sentences within the paragraph is clear and fully logical, then the secret of coherence lies in the use of transitional expressions between the paragraphs. Important as transitions are, they should be relatively brief and inconspicuous . Virtually a mechanical feature of style designed to make the machinery run smoothly and easily, they should not be labored or artificial, nor should they protrude so awkwardly that they distract the reader’s attention from ideas. Within and between sentence; When used within the sentence, transitional devices usually come between clauses; when used between sentences, they occupy a position near or at the beginning or the end of the sentences they link. Coordinating conjunctions, subordinating conjunctions, and conjunctive adverbs are good transitional devices. Transitions help your paper flow from one point to the next, or from one thought to the next. Avoid lame transitions like also or another. Remember that even in fiction stories a transition can help the reader keep track of what is happening. “The first thing he noticed about her was …” “Finally, the intruders face came into view …” Here are some suggestions for effective transitions Keep an extra copy of this at your writing desk or in your journal and add your own transitions when you discover a new one. Later, you may discover that your getting in a rut. That is when you can go to your new list and try to incorporate something new into your writing. Continual practice at this will help you grow as a writer. To indicate contrast And yet, after all, at the same time, although true, but, for all that, however, in contrast, nevertheless, notwithstanding, on the contrary, on the other hand, still, yet, in spite of To indicate addition Again, also, and, and then, besides, equally important, first, finally, further, furthermore, in addition, last, lastly, likewise, moreover, next, second, secondly, third thirdly, too To indicate comparison Likewise, in a like manner, similarly, To indicate summary In brief, in short, on the whole, to sum up, to summarize, in conclusion, to conclude To indicate special features or examples For example, for instance, indeed, incidentally, in fact, in other words, that is, specifically, in particular To indicate result Accordingly, consequently, hence, therefore, thus, truly, as a result, then, in short To indicate the passage of time Afterwards, at length, immediately, in the meantime, meanwhile, soon, at last, after a short time, while, thereupon, thereafter, temporarily, until, presently, shortly, lately, of late, since To indicate concession At the same time, of course, after all, naturally, I admit, although, that may be true Recommend Books on Writing Universal Keys for Writers by Ann Raimes, Houghton Mifflin publisher. ISBN 0-618-11288-X Revision by David Michael Kaplan Story Press Woe is I by Patricia T. O’Conner Grossett Putman Word Painting by Rebecca McClanahan Writers Digest The Right to Write by Julia Cameron Putnam Publishers Writing In Flow by Susan K. Perry Writers Digest Bugs in Writing by Lyn Dupre’ Addison Wesley,. Sleeping Dogs Don’t Lay by Ricard Lederer & Richard Dowis St. Martin Prss The Associated Press Stylebook and Libel Manual Addison Wesley These books are available at most bookstores, and can be from most online bookstores such as www.amazon.com www.borders.com www.half.com Writer’s Statement Before you start your first essay it will be helpful to make some decisions about who will read this paper, what areas you will cover. I suggest doing a free-write about your paper. The extra time used in this exercise will prove helpful in the end. Write a one to two page summary about the paper you intend to write. Of course, things may change as you begin to write your essay. You may decide to refocus your topic or even change your topic. However, in order to get started you need to establish some boundaries. Therefore, in this short paper write a letter to an imaginary editor your intentions. This writer’s statement should include, but not limited to; Territory What is your topic? What area of expertise (if any) do you have that qualifies you to write about this topic. What do you want to learn from this essay? Is there something about this topic that you do not understand? What are the gaps in your knowledge. Why does this interest you? Audience Excluding the instructor, who is the intended audience? You have something to say, but to whom do you want to say this? Will it be read by religious people only? Or will it be read by an audience that may not be familiar with religious terms? Answer the following questions; Who would you like to read your essay? One person, small group, large group, general audience. Readers who are likely to be interested or uninterested. Readers who are likely to be favorable, neutral, or hostile. Readers who are likely to be easy to persuade or difficult to persuade. Readers who likely share these attitudes, characteristics, or experiences; age, religion, sex, race, income, education, politics, etc. What does the average reader know about the subject? Readers who know more, same, or less than I do on the subject. Readers who are well informed, somewhat informed, poorly informed about he topic I should use technical, general, or simple language. How can I reach my readers? I share these values and attitudes with readers. Readers who probably care most about these issues or problems. Readers who have; great, some, little power to affect me. Active Verses Passive Voice Unless you have a good reason to do otherwise, always choose the active, rather than the passive, voice. With the active voice, the agent (the person or thing carrying out the action expressed by the verb) is the subject. John opened the door In the passive the person or thing toward which the action is directed is the subject of the sentence. The door was opened by John The verb “to be” [am, is, are, was, were, be, being, been] often flags the passive voice. Consider; The animal crept closer and closer, and he shuddered with the certainty he would die. The certainty of death was making him tremble, and his space was being crowded closer and closer by the animal. In trying to build suspense the first is obviously better, because it uses active voice. It charges the story with life. The active voice is direct and straightforward. Active Passive Rex pulled the trigger. The trigger was pulled by Rex. Active Passive Bill hit the man in the head. The man was hit in the head by Bill. Active; Passive; Frank Turned the wheel. The wheel was turned by Frank. Active; Passive; Mary shouted at the boat. The boat was being shouted at by Mary. Active; Passive; The door squeaked open. Squeaky sounds were being made by the door as it opened. Of course, there are a few occasions when the writer may want to use the passive voice. Passive voice can show distance in relationship, thus reflecting unimportance. However, when writing can be improved by changing the passive to the active, it should be done. In addition, the active voice uses less words, which aids in keeping the reader’s attention. Indiana Bible College Distance Learning Rubric for Distance Learning Essay Papers The following guidelines will be used to grade your essay papers for Distance Learning. Proof read your paper and use this guide to critique your own paper before sending it in for grading. A few suggestions are listed but obviously not all points can be listed. For example, to list all potential “Mechanics” problems in an essay would require more than the space of this paper. MLA Setup 10 points Follow Modern Language Association guidelines for all papers in Distance Learning. Double space. Use 12 point font (preferably Times New Roman) A Works Cited page should be included at the end. Your name, class, instructor, date; justified left at the top of the first page. Title 10 points Centered / Uppercase first letter of each word except words of three letters or less The title must be creative and unique (Paper Two is not a title) Do not underline the title Mechanics 10 Points Such things as Two spaces after every period Indent paragraphs No words uppercased unless MLA requires it Paragraphing 10 Points The average paragraph should not be longer than ½ page each. If in doubt start a new paragraph. Introduction and Conclusion 10 points Each essay should have an introduction and a conclusion Length 10 points 10 points will be deducted for each page under the minimum essay length requirements. For example; A five page requirement must be at least five pages. (4 ¾ pages will lose a letter grade). Spelling Typo’s 10 points minus one point for each spelling or typing error (this includes wrong words) Content 30 points Grade Feel free to make copies of this rubric for future use MLA (Modern Language Association) In MLA style you briefly credit sources with parenthetical citations in the text of your paper, and give the complete description of each source in your Works Cited list. The Works Cited list is a list of all the sources used in your paper, arranged alphabetically by author's last name, or when there is no author, by the first word of the title (except A, An or The). The writer should attempt to blend the quote within the context of the paper so the quote appears part of a seamless paragraph. Following are a few examples of methods to incorporate a source in the text of your paper: The first Christian Web site appeared in 1992, and online religion has since become a lucrative Internet business (Jones 39). According to Stanley Jones, a “vast majority of people who consider themselves Christians never attend church” (Jones 52). I agree with Stanley Jones who explains in his book, Secret Christians that few people “are converted by the Internet, yet numerous Christians violate their commitment to Christ by visiting non-Christian sites” (Jones 199). For many Christians “the Internet becomes a trap where their spiritual growth is ambushed by the various pop-ups that draw them into pornography” (Jones 155). About the Works Cited Page The Works Cited page list each work that the writer has quoted within the paper. The requirements for the numerous sources are almost endless, but following are examples of the most often cited sources. For a complete list, students should purchase a college handbook that contains MLA style, or visit the MLA website. (http://www.mla.org/style_faq) The General Form for Citing Books should include (in the following order); Author's name. Title of the book.* Publication information (city of publication, publisher's name, and the year of publication). Title of book should be underlined or in italics. Example; Smith, John. The Prairie Fire and End of the Buffalo. New York: Ballentine, 1992. Book with two or more authors: Smith, John, and Jane Doe. Two Styles of Rhetoric. Boston: Putnam, 1989. Book with editor, or author and editor: Hartman, Phil C., ed. Channels of the Mind. Ogden, Ut: Psychic, 1978. Gooding, Josephine. "How to Get in Touch with Yourself." Finding Answers. Ed. Mary Kinsey. New York: Tanning, 1983: 29-47. Multivolume Work: Princeton, Charles. A History of Tibet. 3 vols. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania, 1947-49. Computer Software: Rosenberg, Theodore J., and Ted Shapiro. Encarta. Computer software. Microsoft, 1993. Films, Filmstrips, Slide Programs, or Videotapes: It's a Wonderful Life. Dir. Frank Capra. With James Stewart, Donna Reed, Lionel Barrymore, and Thomas Mitchell. RKO, 1946. The End of the Buffalo. Videocassette. Prod. Society of American History, 1987. 34 min. Anthology McNally, John, ed. Humor Me: An Anthology of Humor by Writers of Color. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2002. Encyclopedia Article “Magna Carta.” The New Encyclopedia Britannica. 15th ed. 1998. Journal Article Myerson, Joel. “A Calendar of Transcendental Club Meetings.” American Literature 44 (1972): 197-207. Sound Recording (CD) Copland, Aaron. Long Time Ago: American Songs. Saint Paul Chamber Orch. Cond. Hugh Wolff. Teldec, 1994. WWW Home Page The Edith Wharton Society. Ed. Donna Campbell. 5 Aug. 2003. Gonzaga U. 14 Aug. 2003 http://guweb2.gonzaga.edu/faculty/campbell/wharton/indexa.html>. Library Database Clark, Zsuzsanna. “From Saturday-Night Poetry to Big Brother.” New Statesman 21 July 2003: 32. Academic Search Premier. EBSCOHost. Ohio State U Libs., Columbus. 14 Aug. 2003. Works Cited Smith, John. The Prairie Fire and End of the Buffalo. New York: Ballentine, 1992 Smith, John, and Jane Doe. Two Styles of Rhetoric. Boston: Putnam, 1989. Hartman, Phil C., ed. Channels of the Mind. Ogden, Ut: Psychic, 1978. Gooding, Josephine. "How to Get in Touch with Yourself." Finding Answers. Ed. Mary Kinsey. New York: Tanning, 1983: 29-47. Myerson, Joel. “A Calendar of Transcendental Club Meetings.” American Literature 44 (1972): 197-207.

© Copyright 2026