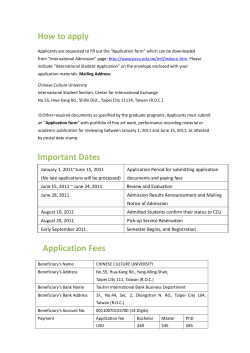

Document 215298