Cut-out for study copy

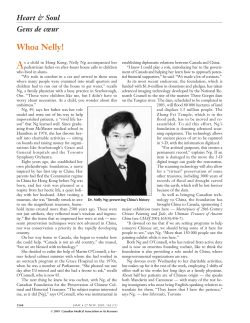

Cut-out for study copy Examiners look for (a) your understanding of how literary features work; (b) how these features convey meaning to the reader; (c) your awareness of the “context” of the extract. The first “E” (the extract in context) can be analysed separately from your interpretation of the extract in your introductory paragraph. L-E-P will help you “close read” evidence, paying attention to why linguistic or literary techniques and choices are made by the writer. Essential Steps What and How E Definition the significance of the extract in the context of the whole story / plot – the “big picture” Extract in context Examples the first time the reader hears Catherine speak, the transition from primary to secondary narrator, first psychological insight into Heathcliff What is the ‘purpose’ of the extract within WH? Definition the bread and butter of literature – the techniques used by the writer to convey meaning L Literary / linguistic feature Examples direct discourse/dialogue, free indirect discourse, monologue, dramatic action, reporting verbs, adverbials, pronouns, modals, adjectives, interjections, rhetorical questions, imperative (directive), subjunctive, comparative, superlative, intensifiers, exclamation, pauses, dashes, stops, images, metaphors, alliteration, frame narration, “simplicity”, circumlocution, convoluted, juxtaposition How is the narrative told to the reader? E Effect of feature Definition the “feeling” or “quality” the reader gains from this particular feature Examples stuttering, agitated prose, sense of catharsis, haunting quality, urgency, imposing, commanding, aligns the reader with the speaker, comic, ironic, mocking, poignant What qualities does the feature have? Definition what this feature reveals about theme, setting, character, the speaker or narrator or what Brontë is suggesting to her (enlightened) reader P Purpose of feature (Note that this is linked to the “extract in context”) Examples shows Nelly’s complicity with the Lintons, highlights extreme contrast between TG and WH, suggests Hindley’s innate childishness, Brontë’s reader sees here the early beginnings of Heathcliff’s desire for revenge, Brontë suggests that her reader should question Nelly’s intentions... What is conveyed to the reader? Why is this important at this point in the text? Cut-down feature cut-up Ignore at your own peril! These truly are the bare fundamentals for presenting your understanding of how Wuthering Heights is a literary text and not a novel you read just for ‘content’. Literary / Linguistic Features General Effect or Purpose Pronouns Establishes intimacy or distance between the speaker and another character Eg. Catherine’s use of “we” to represent Heathcliff and her Modal Verbs Eg. Heathcliff’s shift from “shall be” to “like to be” to “will be” in Ch V Tentative possibility (can, may) Assertive obligation (must, will, should, shall) Ambiguity (can, may) Certainty (will, must) Verbs Eg. Catherine “snatch[es]” and “pinch[es]” Nelly in spite Passive verbs (eg. I was fed) can suggest objectification, while active verbs (eg. I murdered him on court) imply will, desire, power, agency. Dynamic verbs (eg. hit, run) indicate action and control, contrasted by stative verbs (eg. know, am). Use of present continuous tense (eg. walking, driving) can create a sense of immediacy. Direct Discourse Frequent use of dialogue / ‘reported speech’ by both narrators ‘Monologue’ Eg. Heathcliff’s “soliloquy” in Ch V Provides reader semblance of objective, direct narration of events (but not necessarily). Also puts the reader closer to the “reality” of the story Reveals ‘accurately’ and in great detail a character’s thoughts, desires and psychological state. Similar function as the use of the letter. Often used by Brontë to present inner anxiety / unease, “monologues” are protracted dialogues where one character speaks without interruption by speech or narration. Reporting Verbs Eg. use of “exclaimed” in lieu of simply “announced” Adverbs / Adverbials Eg. Catherine (as told by Nelly) to reply “peevishly” and “rising to her feet” like a child Adjectives Eg. Lockwood’s detailed description of Heathcliff as “dark-skinned”, “rather slovenly”, “rather morose”. Conditional clause Parts of a sentence that start with “if”, “unless”, “when”, “except” Marc Kenji Lim Illustrates vividly the manner of speech, in turn relating something about character or character relations Also conveys the “behavioral” aspect of speech (more on action and gesture) to suggest aspect of character(s). Enhances presentation of setting or character but also reveals something about the speaker (from his / her choice of words). Presents the degree of possibility of things happening, from impossible to remote to likely to near-certain. 2 Interrogative Questions fielded by characters to gain information or to intimidate Questions and rhetorical questions (you know?) can suggest the power of the speaker over the ‘addressee’. We usually assume that the ‘askee’ is privileged over the ‘asker’. Questions however can be imposing or patronising, highlighting that the ‘interrogator’ is in control. Imperative Eg. Nelly’s demand for Catherine to simply, “Answer”. “Remember this.” “Write this down.” Short lines without a subject (eg. you, my students, worker-ants) are demands, commands, directives that imply the agency or power of the speaker. Exclamatory Can express unfettered or even exaggerated sense of excitement, joy, anxiety, rage. Reader encouraged to doubt characters who exclaim all the time. It’s irritating! Seriously! Yes, really! Conjunctions Used to communicate contrast, similarity, addition, subtraction, cause and effect. Conjunctions can be split into coordinating, correlative, subordinating. Eg. Lockwood exclaims, “This is certainly a beautiful country!” But, and, or, yet, so, also, both, because, althought etc. Dash Frequently - frequently - used in Brontë’s dialogue. The one defining feature you cannot miss. Interrupts previous line. Draws attention to incomplete lines and fragmentation of thought / speech patterns. A character with a lot of dashes in his or her speech is likely to be overwrought with emotion, distressed, anxious as he or she stutters, rants or rambles. Italics Intensifies what the italicised word usually conveys. The italicisation of “her” focuses the reader’s attention on Heathcliff’s ‘servility’ to Catherine and Catherine only. Also suggests something about the narrator’s subjective viewpoint (Nelly is emphasising her own speech!) Intensifiers Words such as “very”, “extremely”, “exceedingly” enhance meaning or effect deliberately. This can reveal more about the speaker’s own position, bias, judgement. Eg. Catherine’s power over Heathcliff – “how the boy would do her bidding in anything” Eg. Nelly’s use of “very” to describe how “spiteful” Catherine is Comparative / Superlative Eg. Nelly declares Heathcliff “the most unfortunate creature ever born” should Catherine marry Edgar. Frame Narrative The “story” of Heathcliff, Catherine et al is communicated through the central “plot” of Nelly narrating to Lockwood. Comparative words (more, better) highlight the contrast between two subjects. The superlative (most, best, worst) marks the strongest possible degree. Both features signal the speaker’s own interpretation. The disynchronous syuzhet (plot) distances the reader from the fabula (chronological story). At times, Brontë deliberately pulls the reader away from his emotions, almost asking him to analyse her “hero” and “heroine”. *Note that this list of effects is generic. You should tailor the “effect” to the context of the extract, relating for instance, how the reader gets closer to what Catherine is contemplating in that chapter. The skilled Literature student must illustrate how this “effect” on the reader serves a purpose in Brontë’s narration; remember that the Earnshaws, the Lintons, Heathcliff et al are not real people but constructs by a revered 19th century author! Marc Kenji Lim 3 Essay Cut-and-Paste Chapter IV Isabelle Leong + Extremely succinct + Sharp analysis of literary and linguistic features + Awareness of (specific, contextual) effect - Almost discusses narratology (shift in narrator and its ‘purpose’) but that’s… E This extract in Chapter IV marks the ‘transfer’ from Lockwood to Nelly Dean as the central narrator in Bronte’s frame narrative, simultaneously marking for the reader his entrance into a more veritable account of both the Earnshaw and Linton households. Bronte’s narrators in Wuthering Heights can be said to only be reliable to a certain extent, especially in Lockwood’s case, where more often than not he is prone to comic misjudgement. They are both keen observers, however, who present Heathcliff, Hareton, and Catherine’s lives to us to the best of their ability, this perception and interpretation of theirs naturally somehow coloured by their own opinions. We as readers are thus encouraged to question the information relayed to us about these three characters. By L continually questioning Nelly Dean about the history of the characters, Lockwood already introduces new questions about them to the reader, who has yet to be initiated into this part of the story. He asks Nelly whether “Heathcliff let Thrushcross Grange” because he wasn’t “rich enough to keep the estate in order”; L the use of the interrogative here shows that P he himself is fairly uncertain about the characters’ histories and this in turn P provokes the very question in us readers of Heathcliff’s motives for remaining in Wuthering Heights, and what significance Wuthering Heights holds for him. P This cements Heathcliff as a mysterious character whose intents never seem to be openly displayed. In this case Lockwood is very much like us, the critical reader trying to decipher the characters – however, he is the one who introduces thought-provoking questions surrounding the characters’ history, and is thus always one step ahead of us. Lockwood, in this extract, almost seems a device utilized by Bronte to allow the reader to probe into the mystery that surrounds the ostensible ostracisation of Hareton. He questions Nelly about whether the Earnshaws are an “old family”, and Nelly responds that “Hareton is the last of them” – yet for some reason still unbeknownst to both Lockwood and the reader, Hareton has been “cast out like an unfledged dunnock”. L The words “cast out” seem to suggest an E assertion of power by a supposedly higher authority over Hareton, yet how is it possible that he be relegated t o such a lowly position when his own surname is “carved over the front door” of the very house he lives in? A dunnock being a small bird that follows and feeds the cuckoo, is “unfledged”, rooted to no one specific place and almost condemned to wander in search of its own identity / purpose in life, and P this begets the very question of the reason for Hareton’s outcasting. We uncover his story with the aid of Lockwood, who as an outsider, with no previous involvement or initiation into the characters’ histories, poses questions to the one person who can give him answers: Nelly Dean. Catherine Heathcliff is also, for the first time, directly exposed through dialogue as someone not entirely content with her life, seen in Lockwood’s voiced opinion to Nelly. He states that while “Mrs Heathcliff” “looked very well”, he did not “think” she looked “happy” – L the word “think” here indicates a E tentativeness about Lockwood, for he has no basis on which to make the claim, P emphasizing his opinion of Cathay as something based purely on objective perception. Yet we as readers are inclined to believe him; while the true story of Cathy is only revealed later in the text and we discover Lockwood’s initial assumption to be startlingly accurate, we seem to rely on Lockwood as our guide through the stories of these characters, taking what he says into genuine consideration. This mention of Cathy’s apparent Marc Kenji Lim 4 unhappiness prefigures what will be disclosed to us later – how Cathy was forced into submission by Heathcliff and forced oppression in Wuthering Heights. L Nelly Dean, in this extract, serves as the facilitator to Lockwood’s narration. While in other sections of the novel she relates the story entirely on her own – all within Lockwood’s outer narrative – here she is the one who supplies answers to Lockwood’s probing questions, credible answers at that for she intently observes her surroundings and has been a constant fixture in the lives of the characters. L She states mainly facts in response to Lockwood’s questions; when he asks her whether Heathcliff is not rich enough to keep [Thrushcross Grange] in order”, she answers that “he has nobody knows what money”. Yet she sometimes completes her responses with L subtle interjections of her own opinions, for example commenting that it is strange that people who are “alone in the world” “should be so greedy as Heathcliff”. This hints at P a possible inability to sympathise with Heathcliff’s plight, while also introducing a different take on Heathcliff’s evident miser-like qualities. Thus Nelly Dean cannot quite be labeled as a P purely objective narrator, she as housekeeper and someone familiar to the family’s history will naturally still be prone to a certain degree of subjectivity. Lockwood therefore serves as the instigator and Nelly Dean the facilitator in this extract, with Lockwood’s stance being the clear outsider and Nelly Dean being the narrator who has daily insight and experience in the characters’ lives, and hence is substantially more believable. The two narrators in this extract play important roles in relaying the characters’ lives and histories to us, and while not always plausible or entirely reliable, especially in Lockwood’s case, they in fact are the ones who introduced new perspectives or ways of thought on the characters’ lives, and thus cannot be undermined. Chapter VI Ow Kai Zhen + Very fluent, engaging style + Use of language analysed with skill - Lacks understanding of extract’s “place” in the novel - Could do with more cross-referencing to Heathcliff later in the story (non-chronological) In this extract, Heathcliff is presented a person who is more familiar with nature than with the formal setting of a house and society. He speaks with excitement when describing the exquisite setting of the Linton’s house, but scorns it by adding that he would not “exchange, for a thousand lives, [his] condition here”. This indicates Heathcliff’s stance towards the two Linton siblings and P makes mockery of the rather immature way in which both siblings treat each other. He also expresses his love for Catherine and his ardent admiration of her by comparing to the “idiots” and two Linton siblings, who are seen as being rather weak. Bronte’s use of Heathcliff as a narrator (inaccurate statement by student here) while still using the voice of Nelly allows the reader to see a clearer, and perhaps less biased opinion of the two Linton siblings, as Heathcliff was a child at that time and his innocence might have given readers the assurance that he was telling the truth. Moreover, Heathcliff’s narrative is a ridicule of the behaviour of the Lintons and at the same time portrays them as a rather weak foil to Heathcliff, who “despise” them. Heathcliff appears to be the one who staunchly refuses to be blinded to societal norms, “escaped from the wash-house”. The word “escape” clearly draws a parallel between Heathcliff’s physical escape from the confinements of the house and his unwillingness to be entrapped in a place that does not interest him. He regards the outdoors as “liberty”, once again indicating the fact that he delights more in the “park” than at home. This can also be a reference to Heathcliff’s desire to rebel against authority imposed on him against his will and he purposely heads towards the Lintons’ house just to make fun of them, “burning their eyes out before the fire”. As such, we can see that Heathcliff and Catherine were both mischievious and had typical behaviour of young children, “eleven, a year younger than Marc Kenji Lim 5 Cathy”, who refuse to submit to the control of adults and are very free-spirited, doing as they please, “a ramble at liberty”. At the same time, Heathcliff expresses his dislike for his social environment by the use of rhetorical questions, asked rather for effect than for an answer. Furthermore, the listing of two rhetorical questions in a row only serves to reiterate Heathcliff’s extreme unhappiness towards the activities he finds dull, “reading sermons”, “set to learn a column of scripture names”. From this, it can be clearly seen that Heathcliff is very much a child of nature who does not like to be bound to the table to study. The questions he asks have a tone of childish innocence in them, indicating yet again Heathcliff’s character as a child. Catherine and Heathcliff’s obvious enjoyment in the outdoors shows a stark contrast against the Lintons. The narrative places the description of the Lintons’ house after Heathcliff’s account of their activities outdoors. Although the Lintons have a “beautiful” house with expensive furnishings, “crimson-covered chairs and tables”, their past times are entirely different from that of Catherine and Heathcliff. In comparison to them, Heathcliff and Catherine appear to be more mature, “we did despise them”, and Heathcliff’s love for Catherine also surfaces, “When would you catch me wishing to have what Catherine wanted?” Once again, the question is asked not for an answer, but rather to highlight the differences between the shallow sibling rivalry that the Lintons have and the powerful love that Catherine shares with Heathcliff. Heathcliff’s narrative, however, ends with a scene of violence, “painting the house-front with Hindley’s blood”. This highlights the underlying fierce passion and violence that he would be roused to and perhaps also prefigures Heathcliff’s desire for revenge on Hindley eventually. The narrative builds up tension after the argument of the two siblings, which Heathcliff dismisses through mocking them, “That was their pleasure to quarrel”. As such, “flinging Joseph off the highest gable” is indicative of what Heathcliff has the capacity to carry out. His lack of affection for the others in the extract, except for Catherine, also underlines his feelings towards her. It can also be inferred thus that Heathcliff can be cold and cruel, calling the Lintons “idiots” but also pleasant and loving towards Catherine, “I had Cathy by the hand”. As a result, the complexity of his nature is seen throughout the contradictory personalities that Heathcliff embodies. The narrative presents Heathcliff and Edgar Linton in a direct comparison. Edgar is rather weak, “weeping silently” and in stark contrast, Heathcliff is more active, “we ran”. The personality clash between the more “civilized” Edgar and Heathcliff can immediately be seen. However, Edgar’s role as a rather spoilt child, “petted things”, gives readers an insight to the behaviour of children in the upper class society, and forces one to question if such children are really better off than those who revel in the carefree natural surroundings like Heathcliff. Once again, Edgar is a foil for the character of Heathcliff, who is presented as having a more forceful personality and more likeable than that of Edgar. The exclamation marks in Heathcliff’s narrative, “The idiots!” clearly indicates his disgust towards the attitudes of the children and also serves to emphasise his general dislike of such society in general, preferring the outdoors instead. Although the setting of the house is presented in a very “beautiful manner” with the use of adjectives and colours like “gold” and “silver chains”, the immediate behaviour of the children is anything but enviable. The use of words like “red-hot needles” and “warm hair” indicate the anger that Edgar and Isabella have towards each other over a trivial issue. As such, the gorgeous description quickly followed by an ugly fighting scene has a slight irony to it as it indicates how beauty can be skin-deep. Although the house seems beautiful on first impression, the behaviour of the inhabitants is less so, and is another indication of Heathcliff’s ability to penetrate through the façade and see society for what it truly is. Heathcliff and Catherine are associated with nature, as if seen by their position hiding on a “flower-pot”. Heathcliff’s lack of envy of the two siblings indicate his affliction with the wild and how he feels more at ease around them. He also appears to have a sense of adventure and a willingness to explore into the unknown, indicative of how he can be both loving and Marc Kenji Lim 6 extremely cruel. Heathcliff epitomizes opposites – his love and desire to explore and “glimpse” the “Grange Lights” turns out to be dangerous after all as Catherine “fell down” and eventually becomes discovered by the family. Similarly, the language of violence and “blood” imagery underline extent that Heathcliff can go when roused. The imagery and conflict in the extract between society and Heathcliff, a product of the wild, presents Heathcliff as someone with passions that run deep. Although he does not take to people easily, calling the Lintons run deep. Although he does not take to people easily, calling the Lintons “idiots”, when he is roused, Heathcliff can be both tender to Catherine, “had Cathy by the hand”, and those he loves, while at the same time showing extremely hatred of those he resents and bears grudges against, “Hindley’s blood”. The parallel between Heathcliff and the unpredictable wild is also highlighted in this extract. Marc Kenji Lim 7

© Copyright 2026