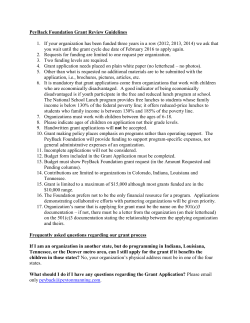

how to apply the access to public information act?