Document 227131

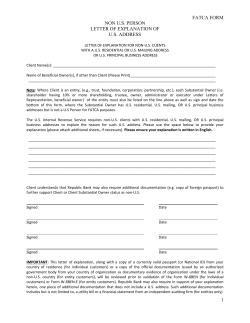

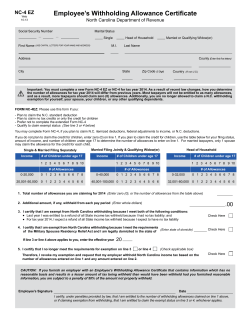

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Special Report HOW TO PREPARE FOR FATCA IF YOU ARE A NONFINANCIAL U.S. COMPANY Kimberly Tan Majure, Principal, KPMG LLP, Washington, D.C. Bruce W. Reynolds, Managing Editor — International Tax, Arlington, VA How to Prepare for FATCA If You Are a Nonfinancial U.S. Company The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act is a complex reporting and withholding regime that was enacted to shed light on offshore accounts, investments, and income of U.S. people who may not have been rigorously reporting those holdings in the past. At a high level, FATCA imposes a 30% withholding tax on what are classified as “withholdable payments” made to a foreign person, unless that person identifies its U.S. interest holders or owners, and discloses required U.S. tax information. FATCA further requires those withholdable payments to be reported annually to the Internal Revenue Service, regardless of whether withholding from the payment had been required or done. Since FATCA was enacted in March 2010,1 a great deal of attention has been paid to issues faced by foreign financial institutions (FFIs), who in fact do have significant compliance obligations involving review of existing accounts; establishing new “know your customer” requirements; modifying systems to track customers, receipts and payments; and preparing for reporting of taxpayer information at varying levels of detail. With the sturm und drang of FATCA surrounding financial institutions, though, relatively little attention had been given until recently to explaining in simple terms (as simple as this area can be made) what an ordinary business must do to ensure that it will be in compliance when FATCA comes fully into force. That point had been as little as six months away; by a notice issued on July 12, 2013, however, the initial implementation of FATCA’s withholding obligations was postponed for another six months, now generally starting on July 1, 2014. This gives everyone a bit more breathing room to deal with compliance. The IRS has issued regulations that detail the fundamental rules2 (although they are informally promising corrections and changes),3 and has issued at least some draft forms that will be used for compliance.4 These set out at least a sketch of the landscape and a path to compliance. A BIT OF BACKGROUND Unusually, although it is structured as a withholding provision, FATCA itself is not actually looking to impose the withholding tax that its provisions call for. When withholding is required, it actually could fall on payments that either would not be taxable themselves, or would go to payees who otherwise would not be subject to tax. The FATCA regime uses withholding only as a penalty to force required information from foreign businesses, particularly focusing on their significant U.S. account holders and U.S. owners, who otherwise might not be reporting their foreign income or assets. The information disclosed by the foreign businesses will be used to check the items reported on the U.S. investors’ tax returns. The revenue that is predicted from FATCA is anticipated partly from FATCA withholding itself, but mostly from increased compliance by the U.S. investors (particularly individuals) who may previously have resisted paying their dues to the taxpayers’ club. In some sense, FATCA withholding operates analogously to backup withholding. Upon receipt of appropriate documentation (IRS forms or other permitted information) from a payee that facilitates the required income-information reporting, the obligation to withhold is automatically 1 FATCA was enacted as part of the Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment (HIRE) Act of 2010, P.L. 111-147, 124 Stat. 71. 2 Regs. § § 1.1471-0 through 1.1474-7, T.D. 9610, 78 Fed. Reg. 5874 (1/28/13). Some modifications were announced in Notice 2013-43, 2013-31 I.R.B. 113 All section references are to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended, or the regulations thereunder, unless otherwise specified. 3 Bennett, “Musher Says IRS to Issue Forms, Agreements for FATCA Compliance Soon,” 92 BNA Daily Tax Rpt. G-11 (5/13/13). 4 W-8BEN (individuals), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-dft/fw8ben--dft.pdf; W-8BEN-E (entities), http://www.irs. gov/pub/irs-dft/fw8bene--dft.pdf; W-8IMY, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-dft/fw8imy--dft.pdf; W-8ECI, http:// www.irs.gov/pub/irs-dft/fw8eci--dft.pdf; W-8EXP, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-dft/fw8exp--dft.pdf. © 2014 THE BUREAU OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS, INC. How to Prepare for FATCA If You Are a Nonfinancial U.S. Company eliminated.5 By contrast, chapter 3 — the provisions that require withholding from payments to foreign persons6 — begins with the presumption that the payments are subject to 30% withholding tax, and uses documentation to determine whether the foreign payee qualifies for a substantive tax reduction or exemption. In that context, the focus of nonfinancial businesses trying to be compliant should be on payee documentation and payment reporting, rather than on withholding. Proper documentation enables a withholding agent to perform the required reporting; proper reporting eliminates any penalty for failure to report.7 Withholding, then, will be necessary only for certain payees lacking proper documentation, and only with respect to certain limited payments. It is also easy to lose sight of the reporting requirements, as a great deal of the spotlight has rested on the timeconsuming and expensive financial institutions’ systems changes that are necessary for those payees to avoid FATCA withholding. For nonfinancials, which are largely making and receiving excluded (but still reportable) payments, the stakes are very different. Procedurally, FATCA joins an already existing, integrated system of documentation, withholding and reporting. The relevant FATCA payee status will be documented using the same forms — although enhanced in length and complexity — as the forms currently used to document status for chapter 3 and backup withholding purposes. Chapter 3 and backup withholding documentation operate much like two sides of one coin. As a working summary of backup withholding, you must have a U.S. payee’s U.S. tax identification number if you are required to send that person a Form 1099 (information return about income). If you do not have a valid tax identification number, then you must backup withhold. You use Form W-9 to document a payee’s U.S. status and also to get certification of the person’s tax identification number. Under chapter 3, if you make a U.S.-source payment of FDAP (fixed or determinable annual or periodical) income to a foreign person, that payment is subject to 30% withholding unless a reduction or exemption can be claimed. Under regulations in effect since 2001, most income items are FDAP,8 and so within that category of income are many items that would also be subject to reporting on a Form 1099 if paid to a U.S. person. A Form W-8 first identifies a foreign person as a foreign person and turns off the possibility of backup withholding.9 It is also used to adjust the withholding tax rate (if a treaty rate reduction applies, for example) or to negate it in appropriate circumstances (if a statutory exemption applies, or the income is “effectively connected income,” for example, and taxed by return rather than withholding). When FATCA joins this mix, the W-8 series of forms will be used by foreign payees to identify themselves; indicate that they are foreign and whether they are a beneficial owner of a payment; and certify to their FATCA reporting status as well as their chapter 3 status. Although the sheer bulk of the revised forms may be intimidating to foreign payees, they will essentially be the same forms that are currently used, just including additional information. Until 2017 (or perhaps later), the payments encompassed by chapter 4 are the same as payments 5 § 3406. 6 Especially § § 1441–1446, which are the provisions determining the amounts required to be withheld. 7 Chapter 3 and chapter 4 require a withholding agent to file a return (which is characterized as an income tax return) on Form 1042 each year. Regs. § 1.1474-1(c)(1). Withholding agents are also required to file an information return (Form 1042-S) reporting payments to each relevant payee, and to provide a payee statement (a copy of Form 1042-S) to each payee. Regs. § 1.1474-1(d)(1). Potential penalties therefore include those for failure to file an income tax return (§ 6651) and substantial understatement (§ 6662); failure to file an information return (§ 6621) and failure to provide a payee statement (§ 6623). 8 Regs. § 1.1441-2(b)(1) [“all income included in gross income under section 61 … except for the items specified in paragraph (b)(2)”]. The effective date was set by T.D. 8856, 63 Fed. Reg. 72183 (1998). See also T.D. 8881, 65 Fed. Reg. 32151 (2000). 9 Similarly, Form W-9 identifies a person as a U.S. person, and turns off the possibility of chapter 3 withholding. © 2014 THE BUREAU OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS, INC. How to Prepare for FATCA If You Are a Nonfinancial U.S. Company that currently are encompassed by chapter 3, although (when withholding becomes relevant) lacking some of the exemptions from withholding that exist under chapter 3. That is, beginning July 1, 2014 — and subject to payments exceptions discussed below — chapter 4 withholdable payments are largely U.S.-source FDAP income paid to foreign persons.10 At the same time, withholding agents will continue to report payee and payment information on Forms 1042 and 1042-S. Principally, Forms 1042-S will report payments to foreign beneficial owners; if the foreign payee is not itself the beneficial owner and documents U.S. people for whom it receives payments (e.g., the foreign payee is acting as a payment agent on behalf of U.S. persons), Forms 1099 may be sent to the U.S. people. The interaction of these three regimes is therefore like three roads that sometimes run parallel, sometimes cross each other, and sometimes go in different directions, addressing similar kinds of payments, classifying payees into one (or more) of the three regimes, and then applying coordinated but separate rules for withholding and reporting. Consequently, a FATCA compliance project should be approached as part of overall withholding and reporting compliance. One of the three regimes is very likely to apply to any payment that you make, and you will need documentation to support your treatment of it; you will need to categorize it for reporting purposes; and you will need to track it for withholding, reporting, or both. Some payments may be exempt from FATCA withholding, but still be subject to chapter 3 or backup withholding. Most payments, especially payments to foreign payees, will be subject to some sort of reporting. Two final points about the coordination of withholding and reporting systems are worth keeping in mind. First, companies thinking about FATCA compliance tend to focus on the remaining periods of validity for their existing Forms W-8, with the thought that the existing forms will provide an efficient shortcut to completing FATCA documentation.11 The regulations strictly define (and narrowly limit) what existing Forms W-8, by themselves, can be used to determine: a payee’s status as a foreign individual, foreign government, or international organization.12 To determine the FATCA status of any other foreign person or entity, the existing Form W-8 must be supplemented with “documentary evidence,” which regulations define to include articles of incorporation; letters from a foreign government; certain filings on government agency websites (such as the equivalent of the SEC); some post-2011 documentation of preexisting accounts; and opinions of regulated professionals such as attorneys — material unlikely to be lying around in preexisting or easily accessible files.13 In addition to documentation generally identifying the payee, one must also have additional documentation necessary to support a payee’s particular FATCA status, such as identification of substantial U.S. owners of a nonfinancial foreign entity.14 Fulfilling the requirement 10 “Withholdable payments” under the FATCA rules consist of (a) payments of U.S.-source fixed or FDAP income, as defined in Regs. § 1.1441-2(b)(1) or -2(c), but without exceptions allowed by that regulation; and (b) after Dec. 31, 2016, gross proceeds from dispositions of property that could produce interest or dividends that would be U.S.-source FDAP income. Regs. § 1.1473-1(a)(1). The July 1, 2014 withholding date is set by Notice 2013-43, which extends by six months most of the starting dates for withholding that were originally set by the regulations. (The post-Dec. 31, 2016, starting date for withholding on “gross proceeds” was not affected by the notice.) Sometime after Dec. 31, 2016, foreign financial institutions will also have to contend with “foreign passthru payments,” which are presently undefined. Regs. § § 1.1471-4(b)(4), -5(h)(2). But, until calendar year 2017, while FATCA might apply to more items of U.S.-source FDAP income than chapter 3 does, among other reasons because exemptions are not allowed, it applies to income of the same type as chapter 3. 11 Regs. § 1.1471-3(d)(1). Notice 2013-43 deems existing Forms W-8 that would otherwise expire on Dec. 31, 2013, to be valid through June 30, 2014, so that new chapter 3 documentation does not need to be secured for the six-month extension period. 12 The latter two statuses are certified on a Form W-8EXP, which is a reasonably rare form in most U.S. companies’ operations. 13 Regs. § 1.1471-3(c)(5)(ii). 14 Regs. § 1.1471-3(d)(1). © 2014 THE BUREAU OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS, INC. How to Prepare for FATCA If You Are a Nonfinancial U.S. Company to supplement existing Forms W-8 with documentary evidence to comply with FATCA’s requirements could easily become a process more burdensome than securing new Forms W-8. Finally, absent any documentation, the final regulations set out presumption rules to determine a foreign payee’s entity status, nationality, and liability to withholding. You should not, however, view presumption rules as a saving grace. They are not intended to, and as a general rule they do not, excuse payments from application of the withholding and reporting rules. Instead, the presumption rules are designed to treat an undocumented payee as subject to one of the three withholding regimes — either FATCA, or chapter 3 withholding, or backup withholding. The presumption rules merely direct a withholding agent to the specific regime that should apply to a particular payment. © 2014 THE BUREAU OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS, INC.

© Copyright 2026