‘Plagiarism and How to avoid it’ - Guidelines for Students.

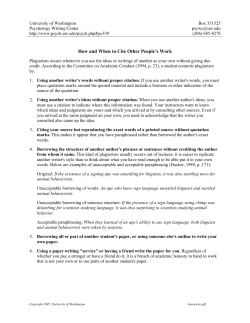

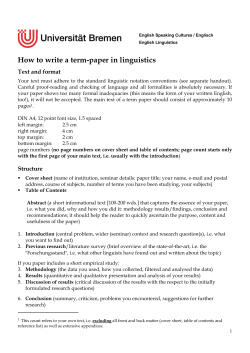

‘Plagiarism and How to avoid it’ Guidelines for Students. Guidelines on academic writing and referencing, to help you use the work of others effectively, without committing plagiarism Academic Session 2005/6 Napier University Business School School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 This document is for the use of all parts of Napier University during Session 2005/2006. It emerges from good practice evolved within, and is authored by the Quality Committee of, the School of Marketing & Tourism, Napier University Business School. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 Contents: Introduction 3 1. Definition 3 2. Copying, Collaboration and Collusion 4 3. Academic Writing 7 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Quotation Paraphrasing and Summarising The misuse of Cut-and-Paste Critical Review 9 12 14 16 4. Referencing 17 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Referencing in the text – Citation Referencing at the end: the List of References Referencing Books Referencing Journals Listing Double References Referencing Electronic Sources Referencing in Exams 17 18 20 21 21 22 23 Procedures for dealing with Academic Misconduct at Napier 23 5.1 5.2 23 5 5.3 Student Disciplinary Regulations The Plagiarism Code of Conduct and the role of the Academic Conduct Officer Detecting Plagiarism: Turnitin® UK 24 24 6 References (for publications cited in this document) 25 7 Further Reading 25 8 Disclaimer 26 Appendix 1 Checklist of Reference contents 27 Appendix 2 Napier University Plagiarism Detection Service Turnitin® UK: Information for Students 28 Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 INTRODUCTION To prepare or submit an assignment, or sit an examination, at Napier University you need to know about Plagiarism. If you don’t, there is a possibility that you will commit an offence of Academic Misconduct. This would render you liable for punishment under Napier’s Student Disciplinary Regulations. This could have serious consequences for your degree. So make sure you read and understand this document. This advisory document has been prepared for students with the aim of helping you write confidently, referencing your work correctly and thus avoiding plagiarism. Plagiarism is considered a serious form of academic misconduct. This applies whether the plagiarism was deliberate or, as we believe often happens, was committed accidentally because students were not aware of exactly what plagiarism is. As with the law, lack of knowledge is not considered an excuse. At Napier, plagiarism and collusion are called Academic Misconduct and are punished as a disciplinary offence. Rather than listing the penalties of varying severity taken against students who commit Academic Misconduct (you can find these in the Student Disciplinary Regulations (see Section 5)), we have taken a different approach. Namely, that the best method of avoiding plagiarism is by raising awareness of it and how to avoid it in the first place. That is what this document aims to do – so please read it. Please note – this document will help you extensively with avoiding plagiarism in your coursework. It is also of relevance to exams, but conventions for referencing in exams vary slightly - see 4.7. 1. DEFINITION A common definition of Plagiarism is as follows: “Plagiarism is passing off someone else’s work, whether intentionally or unintentionally, as your own for your own benefit.” (Carroll, 2002, 9) This definition includes copying and collusion (where the “someone else” is other student/s) as well as passing off the work of published authors. It also highlights that plagiarism may be unintentional, which makes no difference to whether you will be penalised for it. Napier's Plagiarism Code of Conduct (2005, 2) defines Plagiarism thus: Plagiarism is defined … as the ‘unacknowledged incorporation in a student’s work either in an examination or assessment of material derived from the work (published or unpublished) of another’. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 3 Plagiarism therefore includes: i) ii) iii) iv) v) The use of another person’s material without reference or acknowledgement, The summarising of another person’s work by simply changing a few words or altering the order of presentation without acknowledgement, The use of the ideas of another person without acknowledgement of the source, Copying of the work of another student with or without that student’s knowledge or agreement and/or Use of commissioned material presented as the student’s own. In incidences of plagiarism: 3.2.1 Minor misconduct is deemed to include: i) ii) iii) Limited use made of another’s material Limited summarisation without acknowledgement Copying of a minor part of another student’s work 3.2.2 Major misconduct is deemed to include: ‘Substantial or wholesale copying and presentation of another’s work without acknowledgement’. The use of italics here indicates that the Code is quoting directly from the Student Disciplinary Regulations, available at: http://www.napier.ac.uk/depts/registry/Regulations/SDRegs.pdf Note that the "work" or "material" of others referred to above can include ideas, research data, files, algorithms and computer code. The work of others can be taken from any source - including electronic sources such as the internet. Further minor offences of plagiarism can be committed when the format used is misleading - such as when the format used implies paraphrasing, but the material is in fact a quotation, i.e. you are passing off an author's words as your own. This is explained in more detail in 3.3. 2. Copying, Collaboration and Collusion Napier considers collusion as part of Plagiarism. Put simply, it is that part of plagiarism, which is related to the work of other students, rather than to published sources. It also introduces a difficulty: what is the difference Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 4 between Collaboration (seen as acceptable) and Collusion (unacceptable). Before we examine these activities, let’s look at a particularly easy-tounderstand form of Collusion - Copying. Copying other students' work When you copy all or part of another student's work, this is not acceptable. z As you cannot reference the work of another student, it is almost never acceptable. The only exception, where you can use the work of a student - with reference - would be an unpublished dissertation from a student, who studied in a previous year to your own. z Copying applies not only to the content, but also to the structure and / or ideas that are contained within the work. Copying normally occurs as the copying of the exact words of another student, and occasionally as copying other students’ ideas. z You must bear in mind that, unless you are informed otherwise, it is your thoughts that are being asked for, not those of your colleagues. If you present someone else's work as your own you are failing to satisfy the module requirement, and foregoing the opportunity to receive valuable feedback upon your own work. Copying from another student WITH their consent Copying from another student with their consent is just copying in the University’s eyes, and will be penalised. z z z What’s more, the penalty will also be applied to the student who let someone copy their work. If your friends ask you for ideas and you let them have a copy of what you have done, there is a strong possibility that they WILL copy it, even if they say they won’t. In the University’s eyes, you did this willingly, so you are just as guilty of collusion as the person who copied. (That’s what collusion is – an arrangement between two or more people). So don’t do it. However, swapping work after submission and marking may help with your revision and deepen your understanding. So it is permissible. Copying from another student WITHOUT their consent Copying from another student without their consent is a form of theft. You risk someone copying from you if you do any of the following: z z z Save your work onto the hard drive of a computer where other students might access it. Lose a disk or leave a disk or a printed draft of your coursework lying around where other students might find it. Ask someone else to hand in your coursework for you, especially if you are submitting it early. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 5 None of the above is very likely, but they have been known to happen. z z In the above situation, the student who has had their work stolen is likely to be accused of collusion too. A lot of effort will then have to go into establishing the truth. If you believe that someone has accessed or removed your work prior to submission you should inform the module leader. This may minimise the risk of your being accused of collusion. Collaboration and Collusion Collaboration is when a group of you work on a task together, sometimes in informal groups. z This is often a good way of working, as you can bounce ideas off each other and often achieve a better understanding than if you each just worked by yourselves. z Educationally we recognise this is good. This is why we’ve built opportunities to collaborate into our learning strategies in the form of tutorials. Here you get a chance to work together on things and to hear each others’ points of view. You are using this as an opportunity to develop your own knowledge and ideas through sharing and discussing. z However, if as a result of collaborating, you develop common ideas, a common structure and, in many cases, common words for your analysis and proposals, and then each use these, this becomes a problem. The likelihood is that your essays will be very similar, even identical in some places. This would not happen in the normal course of independent study. z You will then find yourself charged with collusion – passing off something as your own when it was actually developed in a group. You can’t even defend yourself by saying you played the major role in the group, because everyone in the group is seen as having colluded. Avoiding Collusion z The only way round this is not to do all the work in a group. z One way is to do it all yourself, which is the safest way. z Another way, if you really benefit from group-working, is to do some of the initial work in a group, and then to move away from the group to finish it off and write it up. Spending more time working alone may be beneficial if you find it difficult to separate yourself from the ideas of the study group. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 6 z In some instances you may agree with what has been said by some of the group members, or want to use textbooks or articles that have been recommended. What you must do is use these in an original manner, ensuring that you do not simply include the same sections or the same points. z Look up some more literature yourself, find some examples of your own, think through your own ideas. z Doing this is likely to make your essay significantly different to everyone else’s (and largely your own work) and you won’t be charged with Collusion. Groupwork When your assessment is based on people submitting groupwork, such as for a group project or group presentation, then, of course, collaboration is expected and will not be considered collusion. z In such a situation, the ideal submission is the opposite of collusion – it is where the work of individuals cannot be identified. The report looks like a unified and consistent whole. z If groupwork is expected, your tutor, your module details and the assignment brief will all have told you this. 3. ACADEMIC WRITING - USING QUOTATION, PARAPHRASING, SUMMARISING AND CRITICAL REVIEW When we use published sources, we usually do so through quotation, paraphrasing or summarising. To do this correctly, we must reference them. Doing any of these four things wrongly may result, intentionally or unintentionally, in Plagiarism. Knowledge about the above techniques and good use of them are essential to avoid plagiarism. Below, we explain the principles of quotation, paraphrasing, summarising and critical review, with plenty of examples to help understanding. Although we will describe citation (inserting the in-text reference) here, compiling the List of References is covered in detail in 4. The text below is drawn from a textbook on the European Union by McCormick (2002) (see section 6 for References). It forms the foundation text on which the examples in sections 3.1 to 3.4 are based. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 7 BASE TEXT FOR EXAMPLES At first glance, the European Union looks much like a standard International Organisation (IO). It is a voluntary association of states in which many decisions are taken as a result of negotiations among the leaders of the states. Its taxing abilities are limited and its revenues small. It has few compelling powers of enforcement, and its institutions have little independence, their task being to carry out the wishes of the member states. None of its senior officials are directly elected to their positions, most being either appointed or holding ex officio positions (for example, members of the Council of Ministers are such by virtue of being ministers in their home governments). However, on closer examination, it is obvious that the EU is much more than a standard IO. Its institutions have the power to make laws and policies that are binding on the member states, and in areas where the EU has authority EU law overrides national law. Its members are not equal, because many of its decisions are reached using a voting system that is weighted according to the population size of its member states. In some areas, such as trade, the EU has been given the authority to negotiate on behalf of the 15 member states, and other countries work with the EU institutions rather than with the governments of the member states. In several areas, such as agriculture, the environment, and competition, policies are driven by more decision making at the level of the EU than of the member states. Where cooperation leads to the transfer of this kind of authority, we move away from intergovernmentalism and into the realms of supranationalism. This is a form of cooperation within which a new level of authority is created that is autonomous, above the state and has powers of coercion that are independent of the state. Rather than being a meeting place for governments, and making decisions on the basis of the competing interests of those governments, a supranational organization rises above the individual interests of its members and makes decisions on the basis of the interests of the whole. Debates have long raged about whether the EU is intergovernmental or supranational, or a combination of the two. At the heart of these debates has been the question of how much power and sovereignty can or should be relinquished by national governments to bodies such as the European Commission and the European Parliament. Britons and Danes (and even the French at times) have balked at the supranationalist tendencies of the EU, while Belgians and Luxembourgers have been more willing to transfer sovereignty. (McCormick, 2002, 4-6) Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 8 Please note that the examples above and below are shown in boxes. This is purely to distinguish them from the rest of the text. You should not yourself put your examples in boxes. Examples of poor practice have that heading on top of their box. 3.1 Using quotation A quotation quotes text exactly as it was originally written. • • • • The quotation should be clearly identified by being differentiated from the surrounding text. Short quotations embedded in your text should have "inverted commas" (often called quotation marks) at the beginning and end. Longer quotations, of more than 50 words or 3 lines, may be identified by indenting the paragraph. The quotation is centred and indented 5 spaces both left and right. When using indented quotes, inverted commas are not necessary. (Leki, 1998, 201) All quotations should be referenced in the text - this is a citation. The citation should include the page number. The page number may take one of three forms, shown in the citations below: • It may be preceded by a p for page (or pp for pages) eg (Leki, 1998 p201); • or by just the date and a comma eg (Leki, 1998, 201); • or by the date and a colon eg (Leki, 1998: 201). • The last version is usually preferred nowadays, but the version used varies by user (and by academic journal). Any of these versions is acceptable as long as you are consistent in using the same method throughout your document. We have used the middle version in this document. Quotations should not be used extensively. Only quote when you wish to emphasise the original words, or they are particularly important. See 3.4 below for the dangers of over-quoting. The proportion of a piece of written work which is taken up by quotations varies according to the work, but a common guideline is 2% to 5%. The examples below are of a short and a longer quotation, with surrounding non-quoted text. EXAMPLE: A SHORT QUOTATION The European Union is frequently described as a "supranational" organisation rather than a "standard" international one (McCormick 2002, 4). Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 9 EXAMPLE: A LONGER QUOTATION The European Union bears many of the characteristics of a standard International Organisation (IO). But it can be argued that it can be classified differently. However, on close examination, it is obvious that the EU is much more than a standard IO. Its institutions have the power to make laws and policies that are binding on the member states, and in areas where the EU has authority EU law overrides national law. Its members are not equal, because many of its decisions are reached using a voting system that is weighted according to the population size of its member states. (McCormick, 2002, 4) The author goes on to argue that the EU also bears characteristics of a supranational organisation. • • It would be possible to miss out parts of the original text. This must be indicated by the use of a set of three dots (ellipsis points) … as in the example below. Please remember that you not should not attempt to change the meaning of the text quoted by using this method. EXAMPLE OF … (ELLIPSIS POINTS) “…it is obvious that the EU is much more than a standard IO… Its members are not equal…” • • It is up to you whether you use “double inverted commas” for your quotations or ‘single inverted commas.’ But you should be consistent. A further, rather specialist consequence of this is explained as follows. King (2000) states that there is no absolute regarding the use of single or double quotes but that if the author uses double quotation marks as the standard device, then s/he should use single quotation marks when inserting a quote within a quote. Similarly, if the author elects to use single quotation marks as standard, then s/he should use double marks when quoting within a quote and so on. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 10 EXAMPLE: A QUOTE WITHIN A QUOTE The rather complex concept of supranationalism “does not mean the exercise of authority over national governments by EU institutions, but rather that it is a process or a style of decision making in which ‘the participants refrain from unconditionally vetoing proposals and instead seek to attain agreement by means of compromises upgrading common interests’” (Haas, 1964, 66 in McCormick, 2002, 6). APPLYING A QUOTATION WRONGLY could include: • • • • Not quoting the words exactly as the original. Missing out a phrase in the quote and forgetting to put in the three dots. Forgetting to indicate a reference. Failing to differentiate the quote or use inverted commas, as below: EXAMPLE: NOT REFERENCING A QUOTE But it can be argued that it can be classified differently. It is obvious that the EU is much more than a standard IO. Its institutions have the power to make laws and policies that are binding on the member states. In the example above we are passing off someone else's words as our own, which is plagiarism. • • • Not referencing something implies that we are saying ”these are our words and our idea.” If a paragraph really is your idea in your own words, and you can't find a way of making sure that the reader understands that, or you think they might not believe it was your idea, you can insert yourself into the paragraph as "the author". E.g. "For the reasons given, the author believes that…" Or you may simply use the passive voice e.g. “It can be concluded that…”, or “it may be reasoned that…”. Referencing something as a quotation implies that we are saying "this is someone else's idea in their own words". Referencing something without quotation marks or indentation implies that it is a paraphrase - that we are saying "this is someone else's idea, which I have put into my own words." If it was really a quotation, then we are once again committing plagiarism - passing off someone else's words as our own. This point is elaborated in 3.3. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 11 3.2 Paraphrasing and summarising Paraphrasing is where you decide not to make a direct quotation but instead to put an author's argument into your own words. It is important that all, or the majority, of what you write is in your own words rather than the author's. If it were in the author's, you could still be accused of plagiarism even if you reference it correctly. Paraphrasing uses roughly the same number of words as the original. More commonly, you may wish to summarise and shorten the argument. Like paraphrasing, you do this in your own words - in fact, the term paraphrasing is often used to include both paraphrasing and summarising. To avoid using too many of the author's words and terms, the best way to paraphrase or to summarise is to read the paragraphs you wish to reflect several times, then put them aside and write your own summary. You should check it against the original text again afterwards. Paraphrasing is cited differently to quotation • • • Paraphrasing and summarising aren't indented or in inverted commas. Like quotations, Paraphrases and summaries should have citations. The reference can appear in the text (see the example below), or at the end of the paragraph. It must always be clear which section of text is paraphrasing or summarising the original; referencing in the text often makes this clearer. Page numbers are not necessary in the reference. Our extract from McCormick could be summarised as follows. (It is so long that it would not be useful to paraphrase it at the same length). EXAMPLE: SUMMARISING McCormick (2002) states that the EU bears many of the characteristics of any International Organisation (IO). Its institutions do not generally operate independently of the member states whose interests they serve and their members are not usually elected. But the EU does appear to go further than this. It can make laws which are binding on its member states and override their laws. It can act on behalf of its members in trade negotiations and effectively makes policy in a number of areas, such as agriculture, the environment and competition. This has led, he points out, to the EU being termed a supranational organisation, with decision-making powers of its own. These powers are often resented. There are frequent debates amongst members and within member states as to the extent to which they have given up sovereignty to the EU and its institutions. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 12 Note how the referencing at the beginning makes it clear that the paragraph is summarising an argument. To make sure that the reader realises that the next paragraph is a continuation of this summary, the phrase "he points out" has been inserted. This is a reporting phrase. Similar commonly used phrases, often with slightly different meanings, include such terms as "he states", "he claims", "he asserts", "he goes on to say", "he develops this argument by stating" and so on. It is often quite difficult to find alternative words or phrases and you may feel it is essential to keep certain phrases as the original. In these cases a small quotation can be inserted into the text, as in the example below (which has been termed "paraphrasing" as it is close to the length of the original). Note how the use of quotation means page numbers must be used in the referencing: EXAMPLE: PARAPHRASING WITH SMALL QUOTATIONS McCormick (2002, 4) states that the EU bears many of the characteristics of a "standard" International Organisation (IO). Its institutions operate with "little independence" of the member states whose interests they serve and their members are not usually elected. But the EU does appear to go further than this. It can make laws which are binding on its member states and override their laws. It can act on behalf of its members in trade negotiations and effectively makes policy in a number of areas, such as agriculture, the environment and competition. This has led, he points out, to the EU being termed a supranational organisation, with decision-making powers of its own. In a supranational organisation "a new level of authority is created that is autonomous, above the state and has powers of coercion that are independent of the state." (ibid, 5) These powers are often resented. There are frequent debates amongst members and within member states as to the extent to which they have given up sovereignty to the EU and its institutions. PARAPHRASING WRONGLY is mainly due to: • • • Using mainly the author's words rather than your own Not referencing Leaving it unclear as to which text is paraphrasing someone's argument and which is your own argument Below is an example of using mainly the original author's words i.e. paraphrasing poorly. Compare it to the original to see the commonality. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 13 EXAMPLE: PARAPHRASING TOO CLOSELY McCormick (2002) states that the EU looks much like a standard International Organisation (IO). Its institutions operate with little independence of the member states whose wishes they must carry out and their members are not usually elected. But the EU is obviously much more than a standard IO. It can make laws which are binding on its member states and, in areas where the EU has authority, EU law overrides national law. It can act on behalf of its members in trade negotiations and in several areas, such as agriculture, the environment and competition, policies are driven more by decision making at the EU level than that of the member states. Some academics argue that the best way to avoid paraphrasing incorrectly is to not do it at all! This recognises the difficulty of putting things into different words and still retaining the original meaning. However, it is unlikely that you will be able to avoid paraphrasing and summarising. You should just try to do it well. And remember - paraphrasing should always be correctly referenced. 3.3 The Misuse of Cut-and-Paste The internet has given students a whole new temptation - to simply cut and paste a useful paragraph into their work and to pretend it is their own work, or their own words. However, the rules for material taken from the internet are the same as for printed material. If you cut and paste a paragraph from an electronic source into your coursework (or copy it into your exam paper): • • It must be presented as a quotation, i.e., it should be indented It must be referenced as a quotation This is because it is using the same words as the original. In recent student work this practice has given rise to a number of variations of types of plagiarism, of varying degrees of seriousness. Three common ones are: • • "Standard" plagiarism. This involves cutting and pasting extracts from articles into the answer with no reference at all in the text (no "citation") nor in the Bibliography. This is sometimes known as “Patchwork Texting”. "Bibliography-only" plagiarism. This involves cutting and pasting as above, with no reference in the text but with an entry in the List of References or Bibliography at the end. In the text, the marker is wrongly given the impression that the words are your own. Moreover, they have no idea whether the Bibliography entry has been used in the text, or where. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 14 • "False paraphrasing" plagiarism. This involves cutting and pasting as above, but with a reference both in the text and in the Bibliography. However, this cut and paste is not presented as a quotation, but just appears as normal paragraphs. This means that you are claiming that it is a paraphrase or summary; that it is in your own words, when in fact it is not. Because it is derived from the internet, material used in the above ways is particularly susceptible to being detected by the Turnitin® UK software, which searches the internet for sources, (see 5.3 and appendix 2 for more information). Bibliography-only and false paraphrasing are considered poor practice and are sometimes penalised in the marking rather than treated as academic misconduct. This is because they are more likely to have been caused through carelessness and because an attempt has been made to indicate the source. However, students who commit these offences often do so extensively - over 50% of their piece of work may be derived in this way. As penalties take into account the extent of an offence as well as its nature, the penalty can often end up being severe, causing failure of the assessment. Remember, even if you had correctly referenced 50% of your work as quotations, it would exceed the 2-5% guidelines mentioned in 3.1 and would have been penalised in the normal course of the marking. (See also 3.4 below). These forms of offence reflect the types of referencing mentioned at the very end of 3.1. An example of false paraphrasing is shown below, using McCormick's text. You would need to compare it with the base text at the beginning of 3. to see that it is in fact a direct copy. EXAMPLE: FALSE PARAPHRASING At first glance, the European Union looks much like a standard International Organisation (IO). It is a voluntary association of states in which many decisions are taken as a result of negotiations among the leaders of the states. Its taxing abilities are limited and its revenues small. None of its senior officials are directly elected to their positions, most being either appointed or holding ex officio positions (for example, members of the Council of Ministers are such by virtue of being ministers in their home governments). (McCormick, 2002, 4-5) Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 15 3.4 Critically reviewing rather than over-using quotation, paraphrasing and summary Sometimes it may be appropriate for you to simply summarise arguments. However, on many other occasions we wish you to go beyond summary and into some of the areas listed below. In these situations, even if quotation, paraphrasing and summarising are carried out, with referencing, in a technically correct manner, they can be over-used. This occurs when very little of your own argument appears in your work and you are over-reliant on others. There is a danger that you will just string together a series of quotes or paraphrased ideas with just linking sentences between them. There is very little of “you” in the work. It would take too long to give an example of this poor practice here. Let's just say that we wish to see you do some, or all, of the following: • • • • • • • Identify common themes in arguments, or schools of thought in the subject discipline Show how each author differs and where they disagree with each other Show how thought in the area has evolved Show how you would classify differing arguments Evaluate authors' arguments and indicate any shortcomings in those arguments, showing why you consider them to be shortcomings Indicate how much more work would need to be done to be sure certain arguments are valid Synthesise the evidence and arguments of several authors to reach a conclusion This ability to critically review and evaluate arguments of others will be asked of you more and more the further you go through your degree. In an undergraduate degree it gets more emphasised in third year and then more again in Honours year. It is even more important at Masters level. Naturally, it is a major component of your Honours or Masters dissertation, where it is important in your Literature Review and Discussion of findings. It is not restricted to your Dissertation, however. So when and how often to use quotations and to paraphrase, and how much time and text to devote to your own evaluation, is a skill you'll learn as you progress through your course. Here's an example of how McCormick summarises thought in the area, which is the subject of the section of his book which we have been using. He's not putting much of his own evaluation of arguments here (this comes later in his book) but he is trying to summarise objectively and briefly, through both quotation and paraphrasing, the different schools of thought in this area: Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 16 EXAMPLE: SUMMARISING THOUGHT IN THE AREA Some observers question the assumption that intergovernmentalism and supranationalism are the two extremes of a continuum (Keohane and Hoffman, 1990), that they are a zero-sum game (one balances or cancels out the other), that supranationalism involves the loss of sovereignty, or that the EU and its member states act autonomously of each other. It has been argued, for example, that governments cooperate out of need, and that this is not a matter of surrendering sovereignty, but of pooling as a much of it as is necessary for the joint performance of a particular task (Mitrany, 1970). The EU has been described as ‘an experiment in pooling sovereignty, not in transferring it from states to supranational institutions’ (Keohane and Hoffmann, 1990, 277). It has also been argued that it is wrong to assume that ‘each gain in capability at the European level necessarily implies a loss of capability at the national level’, and that the relationship between the EU and its member states is more symbiotic than competitive (Lindberg and Scheingold, 1970, 94-5). Ernst Haas argues that supranationalism does not mean the exercise of authority over national governments by EU institutions, but rather that it is a process or a style of decision making in which ‘the participants refrain from unconditionally vetoing proposals and instead seek to attain agreement by means of compromises upgrading common interests’ (Haas, 1964, 66). (McCormick, 2002, 6) 4. REFERENCING In this section the principles of good referencing are discussed, including referencing books, journal articles, chapters in edited books and electronic references. This section can be used for explanation and as a quick guide to referencing. A two-page quick guide to referencing formats will be produced and distributed separately, but it will refer the reader to this Section 4 for detail. 4.1 Referencing in the Text - Citation Referencing is a process which involves creating a brief reference in the text, which refers to a more detailed list elsewhere (normally a Bibliography or List of References). So Referencing always has two elements: • The reference in the text - called a citation. • The listing, with appropriate detail, in the Bibliography/ List of References. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 17 • The format of the reference in the text and its entry in the References section or Bibliography must both be correct. They are also related - the first part of the citation (author, year of publication) forms the first part of the entry in the List of References. • The idea behind this is that the reader, when they come across a citation which interests them, could turn to the Bibliography/ list of References and, using the citation, find the entry immediately. The format for a Citation varies according to whether the citation is a quotation or paraphrase: • • Quotation: (First Author, year of publication, page number) - see 3.1 Paraphrase or summary: (First Author, year of publication) - see 3.2 See the sections mentioned for more detail on citation. The above method is based on the Harvard Method of referencing. Another common method of referencing is to put a number next to the cited text and then give the citation, or even the full reference, at the bottom of the page in a footnote. This is called the British Standard (or Oxford) method. This is not recommended in most Napier Schools, although some subject areas, such as Law, do use it. Most lecturers will accept it if done correctly. If in any doubt, check with your lecturer. You may come across a number of short cuts using Latin, which are often used in the Oxford system: et al: this roughly means "and all the rest". It is sometimes used in a Citation to indicate that the first author is just one of multiple authors e.g. McCormick et al 2003. It is not essential. It does not affect the full references in the List of References, where all authors are listed (see 4.2 "multiple authors"). ibid: this roughly means "the text last cited, just above". E.g. ibid, 5 which means page 5 of the last text cited, which was McCormick 2002. op cit: this roughly means "the text by this author last cited". It refers to the full reference and uses the author’s name e.g. McCormick op cit, so could not be used in the Harvard system 4.2 The List of References - general It is now appropriate that we give some thought to how you should list your references at the end of your document. Any references that you cite within the text, whether quotations, paraphrasing, summaries or concepts, must be listed at the end of the document. These are listed in a separate section which is given the title References (and often referred to as the List of References, or sometimes the References section). You may also want to list a Bibliography, but, if so, keep it separate from the references. A Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 18 bibliography is generally viewed as a list of books or articles that have helped your understanding of the topic but to which you have not made direct reference. However, you may just use one list and call it either References or Bibliography. If you do, all the entries in it should have at least one reference in the text. Remember, as you do your preparatory work, keep a list of your references as you go along. Otherwise you won’t be able to find them. There are a number of different methods of referencing, but the one that is mainly used in academic and business writing is the Harvard method. This is the preferred method at Napier and it is this method that you are advised to adopt unless instructed otherwise. The formats for citations already described used this method; so do the following formats for References. The following remarks use books as an example but give some of the general principles of referencing applying to all formats. References in the List of References or Bibliography are listed firstly in alphabetical order. Where you have used different books or articles by the same author then these are grouped in date order with the earliest first. The date is the last copyright date, not the last date of reprinting. Hence: Aardvark, A. (2000) The Life of the Anteater, Edinburgh, Animal Press Ltd. Aardvark, A. (2001) Adventures of an Anteater, Edinburgh, Animal Press Ltd. Note that the title of the book is underlined. You may chose to use italics for the book title instead of underlining, but you should not use both and be consistent, do not switch between italic and underlining. An italic example is shown here: Aardvark, A. (2000) The Life of the Anteater, Edinburgh, Animal Press Ltd If you have cited texts by the same author that share the same year date then these are identified in the text using letters, e.g. the first citation would be given the suffix a, the second the suffix b and so on. These letters are then used in the reference section to identify which book or article relates to which citation. Hence: Aardvark, A. (2000a) The Life of the Anteater, Edinburgh, Animal Press Ltd. Aardvark, A. (2000b) Ants and Where to Find Them, Edinburgh, Animal Press Ltd. Often, of course, there are multiple authors. They are separated by full stops and commas after the initials, but with the last two separated by the word “and” instead. eg: Aardvark, A., Armadillo, N. and Tapir, U. (2003) Finding ants: Art or Science? Edinburgh, Animal Press Ltd. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 19 Having dealt with the issue of alphabetical order, it is worthwhile thinking about the general rules that apply to presenting the details of individual references. To do this, we are going to develop some templates that can be applied to most situations. The templates provide you with the order in which the information should be listed and also how you punctuate the reference. If you find yourself in a situation that is not covered by these templates, then the important thing to remember is that you should make a record of all of the information relating to the source; this way you cannot be accused of trying to hide your sources. We will look at how to list books, journal articles, double referencing and referencing from electronic sources. You will find examples of good practice in the academic journals stocked in the library, and so the more you read the more proficient you should become. Other sources which you may also reference, in the most appropriate format, include case study materials, lecture notes, Government Reports, algorithms and computer code. The first two are usually similar to books or journal articles. If you are in doubt about the others it is worth consulting a specialist publication such as Fischer, D and Hanstock, T, 1998 Citing References, London, Blackwell at £1.00. Or Pears, R and Shields, G 2004 Cite them right: referencing made easy Northumbria University Press at £3.50. 4.3 Listing References from Books The following format should be used when listing a textbook. The example also shows how you indicate an edition: Author’s (or Editor’s) surname, Initial(s) (Date) Book Title, Edition, Place of Publication, Publisher Aardvark, A. (2002) The Life of the Anteater, (2nd ed), Edinburgh, Animal Press Ltd. Near the front of the book, usually around the second or third leaf, you may find that there are a list of locations relating to the publisher’s offices. If this is the case, then you chose and list the location that is nearest to where you obtained the book. Where the book is a collection of chapters, you will use the Editor's, or Chief editor's name, followed by (ed). However, you will normally be quoting a chapter from a book and so should use the format shown in 4.5. 4.4 Listing References from Journal Articles The method of listing a journal article is similar to that used for books, for example, the presentation of the author(s). Similarly, the journal title is either Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 20 underlined or italicised (not the article title, this is contained in single apostrophes). Issue numbers are included but not the Publisher. The following format should therefore be used when listing a journal: Author’s surname, Initial(s) (Date) ‘Article Title’, Journal Title, Volume Number (Issue Number/Title), page numbers. eg: Aardvark, A. and Armadillo, N. (2001) 'Ants and their nesting habits,' Journal of Ant Behaviour, Vol 5 (Issue 3), 272 – 278. When listing more than one page number you state the first page and the last page numbers of the article, separating them with a hyphen. Where the article is in a magazine and there is no named author, then Anon should be substituted for the author's name. Here there will often be no volume number either, but the date of issue can be quoted e.g.: Anon (2003), 'Red ants of the Amazon' Ant World Monthly, June, 32 - 37. 4.5 Listing Double References Occasionally you may want to cite a reference that you have taken from another article rather than having read the original yourself. This is acceptable practice, although it is preferred that you read the original yourself. However, it has to be acknowledged in the reference section. In such a case you will have two sets of authors. This situation would also apply when citing references from edited books, in this case you would list the chapter author and the editor(s). Here are some examples: Journal Article in Book Author’s surname, Initial(s) (Date) ‘Article Title’, Journal Title, Volume Number (Issue Number/Title), page numbers in Author’s Surname, Initial, (Date) Book Title, Place of Publication, Publisher. eg: Aardvark, A. and Armadillo, N. (2001) 'Ants and their nesting habits,' Journal of Ant Behaviour, Vol 5 (Issue 3), 272 – 278 in Aardvark, A. (2002) The Life of the Anteater, (2ed), Edinburgh, Animal Press Ltd. Journal Article in Journal Article Author’s surname, Initial(s) (Date) ‘Article Title’, Journal Title, Volume Number (Issue Number/Title), page numbers in Author’s Surname, Initial (Date) ‘Article Title’, Journal Title, Volume Number (Issue Number/Title), page numbers. eg: Aardvark, A. and Armadillo, N. (2001) 'Ants and their nesting habits, Journal of Ant Behaviour, Vol 5 (Issue 3), 272 – 278 in Aardvark, A. (2003) 'The habitats of ants', Journal of Ant Behaviour, Vol 7 (Issue 2), 168 – 175. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 21 Chapter in Edited Book Chapter author’s surname, initial (date) ‘Chapter Title’ in Editor’s Surname, Initial (ed) Book Title, Chapter page numbers, Place of Publication, Publisher Note that you identify the editor (s) using the abbreviation ed(s) as well as by the position in the list. eg: Armadillo, N. (2003) “Anthills and their construction” in Aardvark, A (ed) (2004) Ant habitats around the world, pp 86 – 98, Edinburgh, Animal Press Ltd. 4.6 Listing Electronic References The format used for electronic references will depend upon the nature of the document that you are referencing. If it is, for example, an academic journal sourced electronically then it is acceptable to adopt the standard format shown previously for a journal. Likewise, if you are referencing an article that provides the author’s name, then you would list the author and date, but instead of naming a journal or book you would list the web address. Where no specific author is given there are two approaches that are acceptable. The first is to list the ‘author’ as Anon (short for anonymous) and then the detail, including the web page and web address. The second is to list the web page title as a substitute for the author (this would be the standard approach if you were citing an organisation’s homepage). Students sometimes have difficulty finding the page number when they wish to quote from an electronic journal on an academic database. If you encounter this, try accessing the PDF version of the document, where the page number should be visible. To help clarify here are some examples. With these, the in-text citation is also given, as students often fail to realise that it can be just as straightforward with electronic media as with conventional media. Author’s surname, Initials (Date of work, if given) ‘Article title’, web address e.g. <http://www…> (Date of message or date website was accessed) eg: Aardvark, A. (2003) “Red ants”, <http://www.antdigest.com> (July 24th 2003) Citation: (Aardvark 2003) Anon (Date of work, if given) ‘Article title’, web address e.g. <http://www…> (Date of message or date website accessed) eg: Anon (2003) “Ants of the rainforest”, <http://www.antdigest.com> (July 29th 2003) Citation: (Anon 2003) Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 22 Web page Title (Date of work, if given), <http://www…> (Date website accessed) eg: Ant Locomotion (2004), <http://www.antdigest.com> (January 21st 2004) or: Citation: (Ant Locomotion 2004) Antdigest (2004). Homepage. <http://www.antdigest.com> (January 21st 2004) Citation: (Antdigest 2004) If in doubt, decide on the full reference and then make the citation the first words of that. As with the previous examples, the first stage is to record for yourself the source details as you find and use them. This way, even if you make a mistake in the referencing format, you will be able to demonstrate that you have not attempted, intentionally or otherwise, to pass someone else’s work off as your own. An easy-to-use checklist of what to include in references is found in Appendix 1. 4.7 Referencing in Exams The procedure being adopted currently in the School of Marketing and Tourism is that in examinations citations are required (but without page numbers), but that Lists of References/ Bibliographies are not required. This may be changed shortly, particularly if the University adopts a common policy. Further guidance may be issued by your School in the second half of the semester. If written guidance is given – make sure you read it. 5. PROCEDURES FOR DEALING WITH ACADEMIC MISCONDUCT AT NAPIER 5.1 Student Disciplinary Regulations (SDRs) Academic Misconduct is dealt with through the disciplinary framework rather than the normal assessment ones to ensure consistency of evaluation and penalty, rather than individual lecturers deciding for themselves how they will penalise it. These procedures are formally laid out in some detail, with definitions and indication of typical penalties, under “Academic Misconduct” in the Student Disciplinary Regulations. These can be found in the Freedom of Information website (accessed from the Napier homepage www.napier.ac.uk) in Publication Scheme/ Student Administration & Support, Document 13.17. They should also be in your Public Folders on Outlook once you have signed in. These Regulations cover Plagiarism under Academic Misconduct. Nonacademic misconduct is also included in the SDRs. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 23 5.2 Napier University Plagiarism Code of Conduct and the Academic Conduct Officer The University has taken the trouble to lay out its Disciplinary procedures related to Plagiarism in more detail in a Plagiarism Code of Conduct – check out the Registry web pages to find it. This is a helpful document which quotes the SDRs where necessary, but tries to go into detail on the procedures which will be followed in detecting and investigating cases of suspected plagiarism and then imposing penalties if the case is found proven. However, this Code of Conduct does not go into the ways of avoiding Plagiarism, or Referencing techniques, as this Avoiding Plagiarism document does. Hence these two documents are seen as complementing each other. A brief overview of the procedures described in the Code of Conduct is: Detection: This is done by the academic member of staff who marks your coursework (or the Invigilator in exams). They get a colleague to check. Evaluation: Your work and their findings is then passed for further investigation, confirmation and evaluation to a designated member of staff for the School owning the module on which the alleged offence was committed. This is the Academic Conduct Officer (ACO). You are likely to be invited for interview before a final decision is made. (In overseas programmes, your input is likely to be sought by email). If you cannot attend interview a decision will be made in your absence. Application of Penalty: If it is decided that a plagiarism offence has been committed, the ACO (for a case of Minor Academic Misconduct) or a School Disciplinary Committee (Major Misconduct) will apply a suitable penalty. Penalties often involve reduction of marks, but in extreme cases they can even involve expulsion from the University. The range of penalties is included in the Code; the definitions were reproduced in section 1 of this document. You are strongly advised to read this Code of Conduct, which can be found at: www.napier.ac.uk/depts/registry/regulations.htm 5.3 Detecting Plagiarism - Turnitin® UK The University uses “Turnitin® UK”, a software programme provided for universities throughout the UK by JISC [Ref.]. It is “a plagiarism detection software” based on a sophisticated computer system into which your piece of: “written” work can be loaded. This system scans the internet and looks for matches between your work and any material on the internet (it archives material on a regular basis) and in some academic databases. It also Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 24 compares it to work handed in by other students. (and, if all your classmates’ work was input to the system, your own classmates). If it detects a match, your lecturer or the ACO will decide if that match is a justified, properly-referenced quotation or if it represents plagiarism. So this system is extensively used at the investigation stage. It is for this reason that you may be asked for a copy of your work electronically. Your work is treated confidentially, under the principles of the UK Data Protection Act: as described further in the Turnitin® UK Napier University Student Information Document, appendix B. This system is designed to help students check whether they have inadvertently committed plagiarism. So it is possible for a student to input their own work and, when satisfied with their final draft, refer the lecturer to it. Or the lecturer may simply grant the student access to their own file during an investigation. Napier is hopeful that this system can help students avoid plagiarism and it is hoped that its co-operative use will develop in the manner described. 6. REFERENCES Carroll, J (2002) A Handbook for Deterring Plagiarism in Higher Education, Oxford, Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development King, G. (2000) Good Writing. Glasgow, Harper Collins Publishers Leki, I. (1998) Academic Writing. Exploring Processes and Strategies. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press (pp. 199-202) McCormick, J. (2002) Understanding the European Union. New York, Palgrave (pp. 1-6) 7. FURTHER READING http://www.plagiarism.com Uses the Glatt Plagiarism Teaching Programme which is a self-teaching package to help students learn not to plagiarise http://nulis.napier.ac.uk/StudySkills/ Going into this and selecting Bibliographies and referencing gives you a range of links to documents on referencing, including comprehensive guides to various referencing systems. This is on the Library’s own website. http://www.unn.ac.uk/central/isd/cite/ The Plagiarism website of the University of Northumbria, which is very good. Fischer, D and Hanstock, T (1998) Citing References, London, Blackwell. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 25 Pears, R. and Shields, G. (2004) Cite them right: referencing made easy Northumbria University Press Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) homepage, available at http://www.jisc.ac.uk/ (Sept. 12, 2005) JISC is a national body supporting HE and FE institutions to use ICT in teaching, learning and research. JISC Plagiarism Advisory Service (JISC PAS) homepage, available at http://www.jiscpas.ac.uk (Sept. 12, 2005) This is the JISC site for educating and advising students and staff on all issues of plagiarism, its prevention, and detection. Napier University Student Disciplinary Regulations (2005) available at http://www.napier.ac.uk/depts/registry/Regulations/SDRegs.pdf (Sept. 12, 2005) Registry Services Student Records Information available at http://www.napier.ac.uk/depts/registry/studatajisc.html (Sept. 12, 2005) Napier Plagiarism Code of Conduct (2005) available at www.napier.ac.uk/depts/registry/regulations.htm (Sept. 12, 2005) 8. DISCLAIMER The information contained in these pages was written and compiled in 2003 by Stephen Doyle, Dr. Monika Foster and John Revuelta on behalf of the Quality Committee of the School of Marketing & Tourism, Napier University. It was updated and added to in 2004 and again in 2005 by John Revuelta, Dr Monika Foster and Martin Robertson. None of the above-named people nor the above-named Quality Committee are responsible for any use of the information contained within these pages and any losses or consequences which may arise from the use of the information. All information is used at the user’s own risk. Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 26 APPENDIX 1 A checklist of what needs to be included in references for different information source types (adapted from Pears, R & Shield, G (2004) “Cite them right: referencing made easy” Northumbria University Press: 2) Issue Title of Title of Author Year Of article/ publication Information Publication chapter 3 3 3 Place Publisher Edition Page URL Date Numbers accessed Of Publication 3 3 3 Chapter from book 3 3 3 3 3 Journal Article 3 3 3 3 3 3 Electronic Journal Article Internet Site 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Newspaper/ 3 Magazine Article 3 Book 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 3 3 3 3 3 27 APPENDIX 2 NAPIER UNIVERSITY PLAGIARISM DETECTION SERVICE: TURNITIN® UK INFORMATION FOR STUDENTS What is Turnitin® UK? (A JISC Service) JISC is the Joint Information Systems Committee, an organisation funded by the UK Higher and Further Education Funding Councils (HEFCE) and JISCPAS is the JISC Plagiarism Advisory Service. In common with many Universities across the UK, Napier has subscribed to one of the JISCPAS tools called Turnitin ® UK, for the new academic session 2005/06. This is a software package available to staff to assist them in the prevention and detection of plagiarism. How does it work? Turnitin ® UK helps academic staff address a number of common but difficult to identify issues related to citation and collaboration in coursework assessments. It enables tutors and you as students, to identify the original source material included within student work by searching a database of several billion pages of reference material gathered from professional publications, student essay websites and other student works. It is used as a tool to help provide better information and feedback to students about the work they have submitted. The tool does not make decisions about the intention of work it identifies as unoriginal, nor does it determine if unoriginal content is correctly cited or indeed plagiarised. It simply highlights sections of text that have been found in other sources. In many cases this will lead an academic member of staff to provide feedback to you on how to improve your coursework submissions and citations. All assessment decisions will continue to be made by a module leader who will review the entire work. What is the benefit of using the service? Napier University wishes to help encourage you as students to behave with honesty and integrity at all times. The correct citation of work and the authenticity of assessments is a cornerstone, not just of our education system, but of the trust and value held in each of our education institutions by employers and the public at large. Napier wishes the use of Turnitin ® UK, along with other methods of maintaining the integrity of the academic process, to help maintain academic standards and fairness in assessment. How will your data be used? Use of Turnitin ® UK during session 2005/06 is at the discretion of individual Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 28 lecturers. For the service to work, your assignments will be submitted to Turnitin ® UK where they will be stored together with all or a selection of your first and last initials, student email address, course details and institution. Once your material has been uploaded it will be stored electronically in a database and compared against work submitted from Napier or from other UK institutions using the service. Your tutor will receive an Originality Report from the service. In most cases this feedback will be used by your tutor to help you with the process of citation and the importance of maintaining academic standards. In some cases, dependent on extent, level and context, the University may decide to undertake further investigation which could ultimately lead to disciplinary action, should instances of plagiarism be detected. Such decisions are entirely at the discretion of the University. The identity of students who have submitted work to the service will not be revealed to other institutions either by JISC or Napier. How long will the service keep your work? The service will seek to retain submissions until the termination of Turnitin ® UK or its successor, thus helping to accumulate as large a database as possible against which to compare submissions. Who owns the copyright to the work you have submitted? HEFCE has no interest in acquiring the intellectual property rights for the content submitted by you. The University does not normally claim ownership of work produced by undergraduate students. However the University reserves the right to require any student engaged in research or development work to assign to the University all rights to that work. For further information on this please consult the University’s Intellectual Property Policy by using this link Intellectual Property Policy The service will help to protect your work from future plagiarism and thereby help maintain the integrity of any qualification you receive. What are your rights under the Data Protection Act? As the data subject you have the right to see what personal information is held about you in relation to this or any other service that stores your personal information and you have certain rights to object to your data being used. For further information regarding your rights please refer to the Plagiarism Advisory Service website (www.jiscpas.ac.uk and click on Detection Service and then Data Protection) and also to the University’s Data Protection Code of Practice at www.napier.ac.uk/deptsmas/sms/publications/Data Protection.pdf . Code of Conduct on Plagiarism The University has developed a Code of Conduct on Plagiarism for introduction in the new session 2005/06. You can view this on the intranet under Resources or on the Registry Services website at www.napier.ac.uk/depts/registry/regulations.htm. EdDev/S & MS Revised August 2005 Napier University Business School, School of Marketing and Tourism Quality Committee, September 2005 29

© Copyright 2026