International Journal of Political Economy ISSN 0891–1916/2009 $9.50 + 0.00.

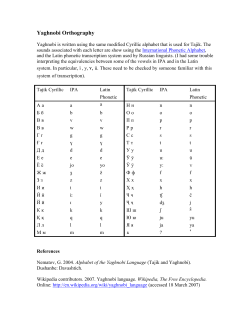

International Journal of Political Economy, vol. 37, no. 3, Fall 2008, pp. 82–108. © 2009 M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0891–1916/2009 $9.50 + 0.00. DOI 10.2753/IJP0891-1916370304 Juan Carlos Moreno-Brid and Igor Paunovic What Is New and What Is Left of the Economic Policies of the New Left Governments of Latin America? In the past ten years, a number of New Left governments have been elected in various countries of Latin America.1 These governments offered their electorate an economic and, in some cases, a political agenda based on the explicit rejection of the Washington Consensus approach to economic growth and stabilization. Once in office, all are implementing economic policies that combine orthodox and heterodox elements that, in diverse ways and forms and to different depths and degrees, depart from the neoliberal tool kit that had ruled the roost in the region since the mid-1980s. To what extent do their policies and programs constitute a new agenda, a new strategy for development? This is an open question. In any case, perhaps its extent of novelty is not as relevant as whether the agenda implemented is indeed helping to place the region on a path of more robust and sustainable economic expansion with a more equitable distribution of income and wealth. At this point, it may be too early to answer fully these questions. Juan Carlos Moreno-Brid is the Research Coordinator and Igor Paunovic is the chief of the Economic Development Unit of the Regional Office in Mexico of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). The opinions here expressed are the authors’ and do not necessarily coincide with those of the United Nations. A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the workshop “Latin America’s Left Turns,” Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada, April 18–19, 2008. The authors thank the participants at this seminar as well as Rolando Cordera, Ciro Murayama, Pablo Ruiz Nápoles, Jorge Eduardo Navarrete, Esteban Pérez, and Mario Seccareccia for their comments. 82 fall 2008 83 This paper updates and extends our previous research on economic policies of the New Left governments in the region (see Moreno-Brid and Paunovic 2006; Paunovic and Moreno-Brid 2007). Its main goal is to examine the industrial policies put in place by these governments and to identify their new elements or characteristics in comparison to the ones previously implemented. With this, we hope to provide tools by which to assess to what extent their industrial policies—whether fully original or not—are meeting the challenges that these countries now face in their quest for development. In addition, this paper shows that, for the purposes of understanding the economic policies of the self-proclaimed New Left governments in Latin America, some of the traditional categories—neoliberalism, social democracy, populism, and socialism—have rather limited value as analytical tools. To be more precise, and as will be seen in the following pages, a category that permeates our analysis is “neoliberal,” as a characterization of policies oriented to curtail severely the role of the State in the economy in favor of granting a fundamental role to the market in the allocation of resources. Unfortunately, although the neoliberal agenda can be rather neatly defined, its alternative cannot. This reflects the fact that there in no single post neoliberal agenda for development. “Populist” is another category that is elsewhere amply used, typically in ideologically charged circles, in a pejorative way to refer, practically by definition, to the economic policies of any Left wing government. This category, however, must be clearly defined for it to have analytical value. For us, it implies a set of policies—usually geared to improve social or economic conditions of a majority or to boost the economy’s rate of expansion—based on (a) the surge of fiscal or external imbalances that cannot be sustained, and (b) the persistent intervention of the government through direct control of prices in key markets in an excessive and unsustainable form, be it in terms of their time duration or of their magnitude. When so defined, whether the regimes of the New Left should be categorized as populist depends on the expected evolution of the region’s terms of trade. If their improvement may reasonably be assumed to be permanent, then most of these regimes in Latin America should not be considered populist. However, if their improvement is merely a temporary phenomenon that will soon be reversed, then the regimes could safely be perceived as yet another set of policy experiments of a populist nature in the sense that will end up provoking an economic crisis. Special attention should be paid to Argentina in this regard, given the government’s 84 international journal of political economy emphasis on price and wage controls as the main tool to curtail inflation and guarantee the domestic availability of certain grains. Our position at the time of writing (May 2008) is that so far and with the exception of Argentina, practically none of these governments can be described as populist, but certainly run the risk of becoming so. Whether or not this happens depends partly on the evolution of the terms of trade and partly on the ability of the New Left governments to: (a) put in place sectoral policies to build up a solid manufacturing base or a service sector able to compete successfully in the world as well as in the domestic market, and (b) to adequately adjust their fiscal and monetary policies in order to face adverse external shocks and avoid overheating the economy. Finally, we believe that the categories of social democracy and socialism do not contribute much to an understanding of the current social and economic transformations in the region. Reasons for the Leftward Shift in Latin America 2 We find two economic reasons behind the recent surge of leftist governments in Latin America. The first and likely most important is the disappointing results of the reforms inspired by the Washington Consensus. Indeed, these liberal reforms—financial liberalization, deregulation, privatization, and opening up of the capital account—failed to trigger a phase of high and sustained expansion. In fact, the rate of economic growth, as well as the evolution of productivity in the region after the liberal reforms, was highly disappointing in comparison with its performance in the four decades of import substitution industrialization and state-led industrialization (SLI). It also pales relative to the performance of other developing economies, particularly in East Asia. When these reforms were fully in place—from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s—Latin America’s growth was very slow, lagging behind that of the developed world as well as of many developing regions. In addition, since then its rate of expansion has been very volatile and subject to major collapses, The Mexican financial collapse of 1995 was followed by other crises, inter alia, in Brazil (1999), Argentina (2000–2002), Colombia (1999), Ecuador (1999), Venezuela (2002–3), Uruguay (1999–2002), and the Dominican Republic (2003–4). Moreover, few jobs were created in the labor market during these years, and the vast majority of them were in the informal, low productivity sector with scant or no social protection. Given such lackluster performance, it should come as no surprise fall 2008 85 that, at the end of the twentieth century, 205 million people lived in poverty in Latin America (close to 40.5 percent of the total population), with 79 million in conditions of extreme poverty. Such proportions were actually not very different from those registered in 1980. Not unrelated, Latin America continued to be one of the most unequal regions in the world (see ECLAC 2007). Indeed, its average Gini coefficient (0.55) was higher than that of Africa and some East Asian newly industrial countries: Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand (with a Gini coefficient of 0.46). Many countries in Latin America also have acute problems of migration. In 2000–5, for example, Mexico had probably the highest rate of emigration in the world.3 The second reason for the emergence of the New Left governments in Latin America is the dramatic improvement that the region has experienced in its terms of trade in recent years, closely related to the booming expansion of some Asian economies that sharply increased the global demand for and relative prices of raw materials, energy, cereals, and grains. This windfall gain brought about a vast increase in fiscal revenues as well as in the supply of foreign exchange to many Latin American countries with a comparative advantage in natural resources. Such phenomenon drastically lifted two key constraints historically binding economic growth in these countries: the fiscal and the balance of payments constraints. And, in turn, they widened the room to maneuver, the degree of freedom available for governments to implement heterodox economic policies, thereby freeing them from the conditionality imposed by international financial institutions. Although the Chinese–Latin American and Indian–Latin American flows of trade and foreign investment are still relatively small (US$40 billion and US$6 billion, respectively), their increasing trends announce a change for our region that reflects a more multipolar world economic order. The surge in South–South foreign direct investment (FDI) is an important element in this regard. Economic ties with China, India, and other Asian countries may become more important for some South American countries given the U.S. economic slowdown and the continued need of Asian countries to tap key natural resources worldwide in order to sustain their own economic expansion. Other than the two economic factors identified here, there are also political considerations that played a role in the shift toward the left in Latin America. On the one hand, many traditional conservative political parties were seen as unable to respond to the growing need of the elec- 86 international journal of political economy torate to address the increasingly worrying job and economic situation of the majority of Latin Americans.4 Another political element behind the shift to the left is the radical change in the geopolitical priorities of the U.S. government after the 9/11 attacks. Indeed, after that date, Latin America appeared to swiftly fade away from the U.S. government’s list of priorities. One indicator of this loss is the weakening of all efforts to establish the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). This goal, once the flagship project to strengthen the economic ties between the United States and Latin America, has practically been abandoned. Recently, in the process leading up to the U.S. presidential elections, there have been some signs of a revived interest in Latin America, as free trade and migration have been topics in the debates among potential candidates. Notwithstanding this, Latin America does not seem to be a center of political concern to the United States. In any case, the aforementioned factors favored and allowed the resurgence of heterodox policies in Latin America advocating, in particular, a larger role for the state in the economy. This included a critical view of privatization and of the role of certain international financial institutions. Not surprisingly, the left-of-center parties strongly advanced in electoral preferences in Latin America. In the past ten years, self-proclaimed leftist governments were elected in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Such a political shift has been accompanied by a drastic reduction in the use of International Monetary Fund financial resources in the region, as countries are benefiting from windfall gains due to favorable terms of trade and the tapping of other sources of funds with no policy conditionality attached to them. Industrial Policies in Latin America: Then and Now A number of differences exist between the industrial policies implemented in Latin America’s era of import substitution and those implemented during the neoliberal reforms. Their objectives are not the same:: the international and national contexts for policy-making have changed in the region; there are conceptual differences in their perspectives ; and the instruments used are different. Finally, there are now certain restrictions, some of which were not present in the past, that constrain the policymakers’ room to maneuver. The liberal reforms phased out the inward-oriented industrialization strategies and eliminated their key policy instruments, whether fiscal, fall 2008 87 commercial, or financial. In addition, fundamental institutions—such as development banks—were dismantled or radically modified. Indeed, in the SLI phase, sectoral policies had as their top priority the promotion of manufacturing activities. The neoliberal reforms shifted their orientation toward a horizontal approach in which incentives were geared towards small and medium enterprises (SMEs) with scant attention to their specific activity. In fact similar incentives were granted to SMEs of any sector—primary, secondary or tertiary (i.e., mining/extractive industries, services sectors, and, in particular, tourism). In brief, with the neoliberal reforms, manufacturing lost the priority it had in the SLI agenda for development. The Context for Policy-making When we compare the context in which the industrial policy was implemented from the 1950s to the beginning of the 1980s with that of the present day, we notice important differences. The end of the Bretton Woods system brought about the elimination of global public goods in the macroeconomic sense, so now each country individually must take care of its own economic stability and bear the burden of adjustment to external shocks. In the past twenty years, such shift of national macroeconomic policies has resulted in the abandonment of growth and employment as key policy targets and has brought about deflationary policies. At the same time, globalization has increased the connectedness and interdependence of the world economy. International trade and finance have made the individual economies much more dependent on what is happening in the world economy. In the realm of ideas, there was a strong shift from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s to a “free market as a panacea” attitude, at the same time that the state’s intervention in the economy came to be associated with inefficiencies. Moreover, combating inflation and fiscal deficits became the main objectives of macroeconomic policy, while growth and employment lost prominence under the assumption that they would reach their potential automatically with the unrestricted operation of market forces. Industrial Policies If we define an industrial policy in a broad sense as a deliberate strategy to create new sectors or strengthen the existing ones in order to diversify 88 international journal of political economy and transform the productive structure, boost economic growth, accumulate technological capabilities and increase productivity, then industrial policies have not disappeared in Latin America. They are still present but in a different form. The neoliberal reforms changed their emphasis and characteristics and came to be known and accepted under the name of competitiveness policies. Another characterization concerns the issue of implicit industrial policies; this includes structural reforms such as trade liberalization, privatization, and financial reforms. Certainly monetary and exchange-rate policies influence the microeconomic conditions in which manufacturing and other firms operate. In fact, in our view the real exchange rate and the availability of credit are likely the most important policy variables that affect the evolution of the productive sectors. These, at times, have created sharp contrasts in the evolution and economic outlook of tradable versus nontradable sectors or firms as well as between firms that are credit rationed and those that are not, for example due to their access to external capital markets. Export Promotion as the Neoliberal Mantra Industrial policy was an integral part of the import substitution that became SLI. The objective was to build the industrial sector of the economy to produce domestically most of the products needed and thus alleviate the external constraint on the economy. As a consequence, policies were restricted to those that promote manufacturing, in particular the production of capital goods. Such interpretation has changed, not in small measure because of shortcomings of the SLI strategy and of the successes of the export-led strategy of the Asian countries. The predominant view today is that promoting exports is necessary for any economy that aspires to develop in the current international context of globalized markets. This has far-reaching consequences for the type of industrial policy, the constraints placed on policymakers, and the instruments that may be used in the process. Sectoral policy today must be an integral part of any strategy for enhancing a country’s international competitiveness and its dynamic integration within the global economy. Recent Industrial Policies The first group of policies refers to efforts to expand and strengthen a particular existing sector. The classic example is the auto industry, which fall 2008 89 even today has a special status. To that sector we could add textiles, confection, shoes, electronics, and some agricultural and mineral products. The policy instruments are fiscal and financial incentives and provide trade protection. The second group refers to policies to enhance agricultural production. The intervention in that sector has been maintained in different forms, including price controls, an anathema to neoliberal economists. However, the emphasis has changed toward instruments of a more horizontal nature and a more complex set of policies stimulating rural development. A third set of policies has developed in sectors in which externalities are known to be pervasive or of special importance for the economy as a whole. Examples include sectors that have high potential for technological innovation, such as telecommunications and electricity, and oil and gas. The policy orientation has been to develop efficient regulatory systems and institutions and to try to strengthen the links between dominant players—mostly foreign ones—and domestic firms in these sectors. Finally, the fourth set comprises policies to help SMEs. In many cases, they consist of efforts to form clusters around a large company. The shoe industry, electronics, pharmaceuticals, and informatics are examples from different Latin American countries. Legitimacy of Policies Paradoxically, all four groups of policies are seen as legitimate to varying degrees but are not considered industrial policies. Some, especially the policies to develop the SMEs, have even been favored by the international financial institutions, otherwise strongly opposed to State intervention in the economy, on the grounds that they would help create employment. The paradox is that any intervention in the economy to change the rules of the game and thus favor one sector over the rest, or one group of enterprises over others, is indeed a form of industrial policy. Perhaps the most obvious example is the favoritism with which governments have treated investments in the in-bond offshore assembly industry (maquila). To attract the investment in certain sectors, governments have offered numerous incentives, including exemptions from import duties, valueadded tax, corporate tax, and so on. These measures are perceived as “neutral,” although they radically change the cost structure in certain sectors, giving them advantage over others. Apart from maquila, other sectors such as tourism, forestry, mining, and others have received lavish exemptions from paying taxes, which has helped convert them into the 90 international journal of political economy most dynamic sectors of the economy. In essence, these are all forms of industrial policy in its broad definition, and their effects are no different from the effects of the industrial policies of the past. Creation of New Sectors Perhaps the most significant difference between the industrial policy of the SLI period and of the neoliberal perspective is the latter’s explicit rejection of the goal of creating new sectors and activities. Whereas the purpose and ultimate goal of industrial policy in the past was to create new sectors in the economy, today this is not on the agenda. With the neoliberal reforms, the creation or build up of new sectors through policy measures was restricted to attracting FDI. Transnational corporations were thought to bring in new products and methods of production to a host country, formally leading to a more diversified economic structure. However, the country may not necessarily acquire the knowledge of the production process and thus may find itself unable to replicate it in case the foreign company leaves. This phenomenon occurs particularly when FDI lead merely to the creation of enclaves in the host economy, with scant connections with the local firms. In such cases, there is a tendency to petrify the structure of the economy based on low technological content and low value-added in most of its production. The challenge is still to allow for a transition toward a structure technologically more complex with more value-added type of production. State Enterprises Lose Their Functions with the Neoliberal Reforms In the past, state enterprises were one of the main vehicles to advance industrialization. Not only were they crucial to the adoption of new technological processes, but they also had an important social function, namely to absorb the surplus labor coming from rural to urban areas. As we now know, this social function has also been one of the reasons for their demise, elevating the costs of production to unsustainable levels. The divestiture process in the 1980s and 1990s has changed the landscape drastically. Most public firms have been closed down or privatized. In the latter case, however, public monopoly has frequently been turned into a private one, with benefits accruing neither to government nor to consumers. The state enterprises that survived the privatization wave have fall 2008 91 been considered strategic, mostly in the energy cluster or in minerals, including oil, gas, copper, and electricity. Instruments Different from the Past Although tariff and nontariff protection were the cornerstones of the SLI type of industrial policy, up until very recently they have hardly been used in Latin America. This is surprising given that developed countries rely on them without hesitation, especially where agriculture is concerned. Instead, the focus has shifted to policies of attraction of Federal Direct Investment (FDI) and export promotion. Three groups of instruments have been used to attract foreign investment. The first is based on incentives, fiscal and financial, of the free economic zones type. The second is the attempt to create an efficient environment for investment with quality infrastructure, rule of law, access to foreign markets, transparency, and so on. The third is the attraction of foreign investment on the basis of qualified personnel, a scarcity in a resource-abundant region. Other instruments utilized widely, mainly of the fiscal and/or financial nature, are those that favor exporters or certain sectors. Public investment, although lower as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) than before, is used to connect the more backward rural areas with prosperous urban centers, and public social expenditure is used to mitigate the worst effects of poverty and inequality. Subsidies to agriculture have survived the structural reforms period, although to a much lesser extent than before. On the contrary, different types of instruments, including subsidies, to promote SMEs have been on the rise. Constraints on Policy-making Constraints on policy-making were transformed as the instruments of the public sector were curtailed in scope and number. Indeed, the variety and scope of policy instruments, both microeconomic and macroeconomic, that are available today to policymakers was cut short as a consequence of the structural reforms in the 1990s and the restrictions imposed by multilateral and bilateral agreements. In a world dominated by a freeflowing financial capital and with capital accounts with the balance of payments totally opened, the exchange rate could scarcely be used for industrial policy purposes. Multiple exchange rates, once used frequently, have completely disappeared. Monetary policy has a mandate focused exclusively on ensuring stability of prices, and, coupled with 92 international journal of political economy the autonomy of central banks, this goal is unlikely to be changed in the near future. Fiscal policy, under pressure to reduce the deficit, has less room for subsidies than before. Moreover, it has been crippled on the revenue side by the policy of giving fiscal incentives to FDI and by the trade liberalization that has taken away a large part of the tariff revenues. Development banks, subsidized credits, and export targets have also all but been eliminated. In sum, open economies today face much stronger constraints than the rather closed economies of the past. The Role of the State in the Development Process The role of the state in the development process has been weakened. This loss of the maneuvering space of economic policy with the neoliberal reforms was accompanied by the downsizing of the public sector, both in institutional terms and in terms of its scope of intervention in the economy. In this process the state’s functions and their new role caused it to be a rather passive spectator of the process of economic development. Predictably, the implementation of policies in Latin America continues to be a fundamental problem. Another problem is the scarcity of fiscal resources, which has roots not only in trade liberalization processes and the “race to the bottom” to attract FDI but also in political economy considerations that result in a widespread inability to collect taxes and impose penalties on tax evaders. Moreover, exemptions are pervasive; in some countries they are estimated to be larger than the total tax intake. A lack of strong civil service systems and the noncompetitive salaries that they receive have created severe problems in some countries. This situation tends to reflect a low level of education and skill of public employees, thereby contributing to the inefficiency of public policies. Distinct Dynamics in the Latin American Region Under the neoliberal reforms, Latin America did manage to register a boom in exports, but it failed to pull the rest of the economy toward a path of high growth of value-added or employment either for the manufacturing sectors or for the economy as a whole. Indeed, as Table 1 shows, the region in general had remarkable success in penetrating international markets for manufactured products but not in increasing its aggregate share in the world’s manufacturing value added (MVA). On the other hand, the share of developing countries in world exports fell, but their 64.5 16.6 7.1 0.9 2.9 0.2 1.9 7.4 0.6 0.7 1.2 0.4 0.2 0.3 0.3 3.3 1.1 0.9 Developed countries Developing countries Latin American and the Caribbean Argentina Brazil Chile México South and East Asia China, Taiwan Province of Republic of Korea ASEAN-4 Indonesia Malaysia Philippines Thailand China India Africa 17.0 5.6 0.8 2.2 0.1 1.1 8.7 1.1 1.4 1.5 0.5 0.2 0.2 0.5 2.6 1.1 0.9 74.1 1990 22.8 5.4 0.8 1.1 0.2 2 15.2 1.3 2.2 2.4 0.9 0.5 0.3 0.7 6.6 1.2 0.8 74.9 2000 28.7 4.4 0.5 0.9 0.2 1.7 17.2 1.1 2.3 2.8 1.1 0.5 0.3 0.5 8.5 1.4 0.8 73.3 2003 18.9 4.3 0.2 0.8 0.2 0.8 7.6 1.3 1.1 1 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.2 1.0 0.3 5.4 74.1 1980 18.3 2.4 0.3 0.6 0.2 0.5 18.6 2.3 2.2 2 0.4 0.7 0.2 0.6 1.7 0.5 2.6 77.9 1990 28.9 4.7 0.3 0.8 0.2 2.7 21.7 2.7 3.1 4.2 0.8 1.6 0.7 1.1 4.3 0.7 1.8 67.3 2000 Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Trade and Development Report (Geneva: United Nations, 2006). 1980 Region/economy Table 1 Share of Selected Developing Economies and Regional Groups in World Manufacturing Value Added and Manufactured Exports, 1980–2003 (in percent) 29.7 4.1 0.3 0.8 0.2 2.2 22.7 2.3 3.0 3.7 0.6 1.5 0.5 1.1 6.5 0.9 2.0 65.4 2003 fall 2008 93 94 international journal of political economy share in world MVA rose significantly. In this regard, Latin America’s performance has been appalling. Internationally, it is the region showing the sharpest contraction in its share of the world’s MVA, most of it happening not only in the 1980s but also in the early 2000s. In contrast, South and East Asia more than doubled their combined share in total world MVA since 1990 to exceed 17 percent in recent years, and China’s share tripled (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development 2006). This distinct dynamism is highly correlated with the composition of the countries’ industrial structure. Countries whose industries are marked by technological upgrading tend to have a more dynamic industrial sector than countries whose industrial activities tend to be concentrated in either resource and/or labor-intensive products. The problem is that, in general, the neoliberal reforms have led to a new pattern of domestic output and export that is concentrated more on natural resource based products at the expense of sectors that have the greatest potential for productivity growth and technological upgrading, in particular the high technology intensive manufactures. As we have mentioned, in the past twenty years there has been a change from an active industrial policy to a more passive one. Have there appeared any new elements in the industrial policy due to the leftward shift in the past couple of years? How are individual countries positioned to benefit from more active industrial policy? Economic Development: Back on the Agenda One of the palpable changes in Latin America is the fact that economic development has returned to the center of discussion in intellectual circles and policymaking concerns. It had also gained presence in the agendas of governments as the region searches for a new developmental paradigm. Although it is still early for a firm conclusion, it seems that the new strategy of development will be based on macroeconomic stability combined with social policies geared to address the high levels of poverty and inequality. Stimulating economic growth and job creation is now seen as a necessary but insufficient step to address economic and social inequalities. However, two other indispensable topics, the modernization of the state and industrial policy, are still relatively low on the practical policy agenda of the New Left. Consequently, there is not much to show in these two important areas, although the word industrialization has begun its slow return into the vocabulary of some policymakers, and more proactive public policies have started to appear. fall 2008 95 No Creation of New Sectors Although the agenda of the leftist governments in Latin America has slowly changed toward more active developmental policies, the creation of new sectors is still pending. This shortcoming is even more striking on industrial activities. Initially it could be explained as the result of the need of the governments to address pressing imbalances on the macroeconomic front, including crises management due to external shocks. However, even when such hurdles were successfully removed, governments in general are not putting in place policies to build up or create new manufacturing or industrial activities. In part this situation is linked to the fact that, although in theory manufacturing was to be the engine of growth, in practice the boom in mineral resources and agricultural products have been the most dynamic forces pulling the economies toward a strong expansion path in the last five or six years. Paradoxically, the expansion and technological sophistication of the industrial sector becomes a more and more pressing need—that is perennially postponed—to be able to drive the economy if and when the boom in raw materials loses steam. This technological development has yet to be seen as an explicit public policy decision. Highly Successful Initiatives Some initiatives are highly successful and represent a stepping-stone for a more comprehensive industrial policy. Even though creation of new sectors is not present as a policy goal, there are some more limited initiatives that have proven to be highly successful. One of the most important is the production of ethanol in Brazil. The endogenously developed technology to produce the biofuel has converted the country into the most advanced and largest producer in the world. This has acquired an additional strategic importance with the decision of the United States to reduce its dependence on the sources of energy from hydrocarbon. The other example also relates to energy, with Brazil. Brazil has managed to reach the point of near self-sufficiency in oil production, even though quite recently it was a large net importer. In the process, Petrobras, Brazil’s state-owned oil company, has become a global leader in deep-water oil exploration. This opens up not only economic opportunities but also a huge potential for expansion of South–South cooperation, which is one of the pillars of Brazil’s foreign policy. 96 international journal of political economy Changes in the Energy/Mineral Sectors A profound change has been taking place in Latin America in the redefinition of the conditions of distribution of rents in the cases of natural resources. Several countries have renegotiated contracts with transnational corporations in order to obtain more revenue from the exploitation of natural resources. Some countries have increased taxes and royalties on natural resources, and the most radical ones have nationalized some sectors such as hydrocarbons in Bolivia and Venezuela and mining and telecommunications in Bolivia. This has drastically increased the fiscal revenues of these nations. For example, Bolivia has increased government revenue from hydrocarbons from US$250 million annually to US$1.4 billion in one year (ECLAC 2008). However, these changes have so far not had any decisive impact on the level of production, technological advances, or movement toward the more processed products, which would increase the value added. Thus the risk is that, if and when the mineral boom collapses, the domestic economy’s dynamic growth path could be derailed. Agriculture’s Importance In the past twenty years, agricultural policy has moved from being sectoral to having a more horizontal character, and from existing in isolation from other policies to a more integrated framework. Left-of center governments have until very recently not changed that basic setup. However, the surge of supply bottlenecks and shortages in key cereals has brought to the forefront concerns about the issue of “food security.” The uncertain effects of climate change on the food supply, the increased demand of such primary production for fuel oil, and the recent riots in some countries due to the increase in food prices are making the issue of food availability a crucial one for policymakers. With its vast territory suitable for agricultural production and top-of-the-line producers, countries such as Argentina, Brazil, and Chile are in a very good position to capitalize on those developments. An important indicator of the renewed interest of the leftist Latin American governments for agriculture has been their participation in bilateral and multilateral trade negotiations. In contrast with the passivity in the previous period, when trade agreements that did not favor domestic agricultural production were signed, there has recently been a shift to more emphasis on this issue. The unwillingness fall 2008 97 of developed countries to reduce or eliminate trade protection and subsidies for agriculture and the asymmetry of trade liberalization proposals have met with stiff opposition from developing countries, with Brazil assuming the role of leader. Lack of Science and Technology The areas of science and technology are very much neglected. Latin American economies today are characterized by a simple production structure that is fragmented and disarticulated with respect to local technological capabilities and has very little endogenous capability to generate knowledge or foster technological innovation and diffusion. The increased participation in international trade has come to be considered the main source of technological modernization, so imported components, FDI, and technology licensing have become a basic source of technological upgrading. The regional expenditure on research and development (R&D) amounted to only 1.6 percent of world expenditures in 2002, superior only to that of Africa and Oceania. Its share of R&D expenditure out of GDP in the region is constant at 0.5 percent, compared to an average of 2.3 percent of GDP in OECD countries, or 3 percent in Japan (ECLAC 2008). As a result, local companies are forced to rely heavily on foreign sources of knowledge and technology. In addition, the recent trend of outsourcing R&D to emerging markets has, with very few exceptions, not included Latin American countries. Brazil is perhaps the only country in the region that has launched a massive program to improve the scientific skills of its young population. ECLAC’s recent comparative study of international competitiveness of Asian and European countries concluded that innovation is only in part a function of the amount spent on R&D. Such expenditure must certainly be increased in most Latin American countries. What is perhaps most urgently required is to implement policies that induce scientific and technological innovation and that allow human capital formation to respond to the needs of the local industrial sector, thus increasing Latin America’s competitiveness in foreign as well as domestic markets (ECLAC 2008). Translatinas A phenomenon that has appeared recently is the expansion of transnational corporations of Latin American origin that invest in this and 98 international journal of political economy other regions of the world. This process, which produces what is known as translatinas, has mainly occurred in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Sectors affected include hydrocarbons, mining, iron and steel, paper, cement, beer, food, telecommunications, air transport, retail, and electricity. The main objective has been to expand markets, and the main vehicle has been the acquisition of existing local enterprises. So far, the process has been carried out without much help from governments. However, this will have to change in the future if the translatinas are to enter into competition on a worldwide scale on sound footing. Even to maintain their present position in the region and be able to withstand the power of transnational corporations (TNCs) that are increasingly vying for their assets and regional presence, the translatinas will have to strengthen considerably. Integration Processes The process of integration is a road—recently rather bumpy—to join efforts to enhance the region’s potential for development. In the past couple of years, there has been a flurry of activity in relation to integration processes in Latin America. The most active region has been South America, where most of the governments are leaning to the left. Old integration schemes such as Mercosur (the Southern Cone Common Market) and the Andean Community of Nations (CAN) have undergone major changes and, to some extent, have given way to new initiatives, the most recent being the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). Perhaps it is not a coincidence that the existence of the UNASUR was proclaimed during the First South American Energy Summit. Indeed, the cooperation in the energy sector seems to drive the cooperation efforts and integration processes in the region. The results so far have not been spectacular, but the announced plans point to a much more coherent and integrated regional energy policy in the future. It is yet to be seen if that dynamism can be replicated in other sectors. Moreover, in January 2007, Uruguay signed an agreement on trade and foreign investment with the United States. This act—though not yet launching a formal trade agreement between the two countries—has been severely criticized by Argentina and Brazil, who consider it fundamentally incompatible with Uruguay’s stance as a member of Mercosur. The relation between Uruguay and Argentina has been acutely strained by the former’s decision to build two cellulose plants in the basin of a river that fall 2008 99 runs between both countries. In addition, commercial relations between Argentina and Brazil have seen an increasing number of conflicts. Among these are the trade restrictions imposed by Brazil on imports of products of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) from Argentina due to allegations of dumping practices and those imposed by Argentina on household appliances imported from Brazil—with the former allegedly preferring to buy them from China or Mexico—on protectionist arguments. Brazil has signed bilateral/commercial agreements with various partners on selected activities, including one with the United States on biofuels and the European Union on energy issues, as well as some with Bolivia, Paraguay, and Venezuela. Industrial Policies in Selected MSEs with Left-of-Center Governments Argentina As in the rest of Latin America, during the SLI period, industrial policy was marked by a conspicuous and strong intervention to promote and protect domestic production. However, the attempts to put in place liberal reforms, first in the 1970s and later in the 1990s, pushed the region toward more horizontal, less selective programs. In recent years the socalled Tango crisis and the subsequent response to it by the government of Nestor Kirchner, which took office on May 25, 2003, with an explicit commitment to leave behind the neoliberal model, brought back more interventionist policies both at the macro- as well as at the microeconomic level. Moreover, by 2006 Argentina had paid back all its outstanding loans with the International Monetary Fund, thus putting an end to the Fund’s conditionality on domestic policy-making. In our view, the adoption of a monetary and fiscal policy oriented to maintain an undervalued real exchange rate has been the crucial policy shift behind the impressive dynamism that has since then characterized the Argentinean economy. Indeed, the massive devaluation of the national currency in 2002 detonated a quick economic recovery based both on exports as well as import substitution in manufacturing activities such as textiles and metal mechanics. It may be important to note that during this recovery in 2003–7, the rate of output growth of construction and manufacturing was substantially higher than that of agriculture. In addition, exports of manufactures solidly expanded. 100 international journal of political economy At the micro level, policy interventions in the industrial and agricultural sectors have been directed much more toward alleviating macroeconomic imbalances than to creating an environment conducive to invest in new industrial activities or in technological upgrading. One example is the imposition of temporary bans and taxes on exports of grains and oilseeds to increase fiscal revenues that ultimately provoked acute and prolonged protests and road blockades by farmers and, in turn, food shortages. Another is the current attempt of the government to prevent energy shortages through a combination of tariff controls and export taxes on the current production of natural gas with the promise of the exemption or tariff freezes on any new gas fields that may be discovered by private entrepreneurs. A social pact based on a series of wage restraints and price controls— including electricity tariff freezes—has been put in place to try to contain inflation and maintain a high rate of economic expansion. These polices have so far been somewhat moderately successful in keeping inflation under control, though not as well as the official figures indicate. In our view, if the domestic economy keeps expanding at its extremely high rate, it seems unlikely that the system of price and wage controls will remain functional for much longer. In addition, it may be producing some price distortions that, if they persist, could adversely affect fixed capital formation and lead to supply shortages and, sooner or later, repressed inflation. Brazil Brazil has historically been a leader in using industrial policy to modernize its productive structure, with remarkable results. At some point during the 1970s there was a talk of the “Brazilian miracle,” marking it as an experience that was to be studied and replicated in other developing countries. During the 1980s and 1990s, as in the rest of Latin America, macroeconomic problems cast a shadow over state intervention in economic affairs and thus on industrial policies. However, in recent years Brazil has made a comeback, building a more promising future during the second term of the President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. In fact, in early 2007, for his now-second term in office, da Silva launched the Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento (PAC)—an economic program to boost public and private investment and push for an accelerated growth rate. He announced that such a growth strategy would have orthodox and fall 2008 101 heterodox elements. On the one hand, fiscal and monetary policy would be oriented to maintaining a low rate of inflation. In addition, private investment would be allowed in areas traditionally in the domain of the public sector, such as oil exploration, ports, and airports administration. On the other hand, the program emphasized the need for more state intervention in the economy through industrial policies accompanied by the creation of a federal fund to grant credit for selected projects (the public sovereign fund). To the extent that the economic recovery continues, the evolution of employment and real wages will keep improving. It should be pointed out that the government has consistently pushed for a strong rise in minimum wages; these increases in minimum wages directly augment the incomes of the formal sector but also the informal sector, where these are systematically used as a reference for wage movements. Contrary to the exchange rate policy in Argentina, Brazil has let its currency markedly appreciate in real terms. This measure has put increased pressure on its domestic manufacturing sector, thereby forcing it to intensify its efforts to modernize and move forward in the value-added chain. Whether these efforts succeed may depend to a certain extent on the favorable effects of industrial policies. Although some firms and industries may benefit from the sustained impulse of the Brazilian domestic market and favorable access to funds, others may face considerable difficulties to survive the intensified pressure of imported goods. Since January 2008, there has been a steep rise in the cost of credit due to certain fiscal/monetary policy decisions meant to slow down monetary expansion and inflation through an increase in tax rates on credit operations and an increase in reserve requirements. However, so far, credit for firms has continued to expand at a fast pace, although not as much for the personal sector. In this regard, Brazil’s development bank, the Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social (BNDES) has become a key player, lending billions of U.S. dollars for industrial projects. Whether such credit expansion will continue in the future is, at the time of writing, unclear and will depend on the government’s response to changes in the international context. With its huge domestic market, its large pool of talented and skilled labor, its relatively developed manufacturing sector, and its historically close ties between the private and the public sector, Brazil is in the best position of all Latin American countries to reap the benefits of more active public policies. Moreover, in contrast with the rest of Latin America, tax revenues in Brazil are very high, close to 37 percent of GDP in 2007 102 international journal of political economy (ECLAC 2008). Also, even though current spending has ingrained rigidities that lead it to rise at a fast pace, the public sector has persistently been able to register significant operative surpluses. Bolivia Perhaps the showcase in Latin America of historically rooted structural difficulties to capitalize on its natural resources, Bolivia has been hampered by institutional weakness, striking inequality, and political instability. Coupled with a low level of education of the majority of its population and the lack of investment on the part of its local entrepreneurs—both to produce for the domestic market or exports—this country seems to be not yet sufficiently equipped to utilize the windfall gains of the impressive increase in its terms of trade to implement proactive policies to build up its domestic industrial sector beyond the production of fuel products. This stands in stark contrast with its successful drive to nationalize the hydrocarbons industry in 2006—the key source of foreign exchange and fiscal revenues—in the country and to launch a more interventionist development strategy, including some fiscal changes aimed at improving the living conditions of the indigenous population. Most important, the Central Bank’s crawling peg policy has avoided any significant appreciation of the real exchange rate. Currently the country is facing the surge of inflation due to certain supply shortages, the adverse impact of floods, and the effects of rising prices of imported foodstuffs and has launched a set of orthodox and interventionist measures to try to contain it. The Evo Morales regime has declared its commitment to using the windfall revenues of energy to increase public investment and rapidly expand the economy’s output and employment. Sadly, such plans have yet to be fulfilled, given the public sector’s historical weakness in its capacity to implement projects.5 Thus, long-term plans may be perennially postponed by the short-term improvisation in the use of public funds to meet short-term emergencies, economic or political. Indeed, although public investment has underperformed, the public administration has rapidly augmented both in its wage level as well as its personnel. However, as long as the public sector’s implementation capacity is not strengthened, the window of opportunity provided by the sharp increase in the terms of trade may be insufficiently utilized. Also, even if some social programs prove to be successful in benefiting the indigenous fall 2008 103 population, their impact and scope will fall way short of constituting a new development agenda. Perhaps the most important measure in this regard is, so far, the agrarian reform launched in November 2006 that allows the State’s expropriation and redistribution to the poor of land that is considered to be either not fully used or illegally owned. The scope and overall socioeconomic impact of this land reform is unclear, as it remains yet to be seen whether the producers will be supported by fresh financial resources. So far, it seems that banks are restricting even more their supply of funds to the rural area. In any case, as the experience of the rest of the region has shown, without the much-needed surge in public investment to modernize infrastructure, the private sector’s fixed capital formation will not respond in a dynamic way. In particular, the lack of infrastructure is a major obstacle for the development of the manufacturing sector, in addition to the lack of bank credit and the unfair competition from smuggled merchandise. These three major problems, though amply recognized, have not yet been tackled by any public policy, program, or initiative of the new government. On the other hand, the prospects for investment in the gas industry have improved recently as Petrobras announced the resumption of investment in the country. However, whether such projects are actually implemented is at the moment unclear, given the still prevailing regulatory uncertainty, as some analysts call it, in the country. Chile With its strong institutions, many of which were built for the purposes of fostering industrial policy in the past, Chile has been hailed as a model of orthodox microeconomic and macroeconomic policies. However, the past sixteen years with four left-leaning governments have shown that Chilean public policies have above all been pragmatic. When there was a surge of capital inflows to Latin America in the early 1990s, Chile applied capital controls to discourage them. In the microeconomic domain, even though the thrust of the policies have been horizontal in nature, direct subsidies to exporters, mining, and the forestry sector have been used during very prolonged periods. Successful experience in fomenting its wine-producing sector, fruits and vegetables for export, or, for that matter, the salmon industry (nonexistent twenty years ago) have proved it capable of transforming the productive structure of the economy in a way without precedent in Latin America. 104 international journal of political economy Uruguay At one point called the “Switzerland of Latin America,” Uruguay has always had a higher standard of living than its neighbors, in no small part because of carefully conceived and applied economic policies. The macroeconomic problems of the past two decades have wrecked havoc on the hitherto reasonable economic policymaking. It should be noted that, contrary to the Argentinean experience, the liberalization process in Uruguay was very limited and did not significantly shrink the public sector. In fact, this sector is still large and the economy remains heavily regulated. State enterprises have monopolistic powers in key areas of the energy and petroleum sector, as well as in telecommunications services. As in most other countries, a more horizontal character has been imparted on industrial policies. However, the country has a potential to develop certain sectors and to occupy niches in the markets of its two huge neighbors, Argentina and Brazil. Its educated and skilled workers and a capable bureaucracy are important assets that could be used more actively in the future. Venezuela Once the most developed countries in Latin America, Venezuela is a typical example of the “resource curse.” Although huge reserves of oil and gas present a potential for economic and social development that cannot be matched, they also bring about a social and institutional structure that is fundamentally oriented toward rent-seeking. Incentives to develop productive activities are so weak and so overwhelmed by the incentive to seek rents that a diversification of the Venezuelan economy remains a distant dream of every president in the past several decades, including Hugo Chavez. Inefficient management of Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), has already resulted in reduced production and decreased investment. The policies of Venezuela could be best characterized as “back to the future” policies that did not work in the past, and it is hard to see how they could have any different effects today. Moreover, recent food shortages and the rise in inflation are apparently perceived by the government as a consequence of a private sector’s reaction, or opposition, to its policies in favor of a socialist economy of the twenty-first century. To this extent, the state’s intervention in the economy seems to be on the rise with further nationalizations conceived more as a threat than as fall 2008 105 a policy decision based on the comparative advantages of the economy. The extent to which such threats will hamper economic growth is yet to be seen. On the one hand, the dynamism of the domestic economy is certain to induce more investment. On the other, the uncertainty concerning future property rights may hinder it. Conclusions: Short- and Medium-Term Prospects and Constraints For the left-of-center governments to continue building a new development paradigm in Latin America, one key precondition is the continuation of the relatively high rates of expansion of the world economy. This has two positive effects on Latin American countries. On the one hand, it maintains relatively high prices for natural resources-and a dynamic demand for exports- their main source of dynamism for economic growth in the past five years. On the other hand, it increases fiscal revenues and thus the government’s potential to maintain an expansionary stance in its expenditure, on current and hopefully on future investment/infrastructure projects. This process, if successful, may boost the chances of reelection of the incumbent leftist governments, thus giving them the time necessary to carry out deeper policy changes. The alternative scenario –of a slowdown or decline in world demand- would force them again to concentrate on crisis management, reduction of external vulnerability, and volatility of growth, relegating the questions of technological catching up, creation of new sectors, and transformation of the productive structure to the back of the policymaking priority list. Moreover the urgent need to compensate the loss of fiscal revenues may break the sociopolitical coalitions behind them. As has been clearly illustrated by the Argentinean and, to a certain extent, the Bolivian examples, the conflict over the redistribution of rents between the government and the transnational corporations can be safely managed both domestically and internationally. However, the struggle over the redistribution of windfall gains among different local/domestic classes or groups of producers may be explosive. Beyond the Existing Specialization Patterns Two decades of structural reforms and the recent boom in prices of commodities have left the region with two specialization patterns. The first, predominant in South America, is based on exploitation of natural re- 106 international journal of political economy sources, and the second, present mostly in Central America, is founded on labor-intensive activities whereby these countries offer cheap, abundant, and low-skilled labor. Mexico has elements of both patterns. The main question of economic development in Latin America in the medium term is how to overcome that pattern of specialization. Due to the absence of more proactive public policies, a specialization of the region’s production structures according to static comparative advantages has occurred in the past two decades. Latin American enterprises participate in global production systems mostly at the lowest end of the technological complexity, performing basic assembly activities and some processing of raw materials. The goal of economic policy in general, and of industrial policy in particular, should be to create comparative advantages of a dynamic nature. This could only be achieved with a technological upgrading and with a set of much more coherent policies than in the past. It should be noted that the dynamism of exports of the service sector in Asia is, in general, greater than that in Latin America. Interestingly, as Dihel and Shepherd (2005) in their study for the OECD showed, the regulatory framework in Asia of the service sector—including banking, insurance, fixed and mobile telephone, and engineering services—is on average stricter than in Latin America. Moreover, the data indicates that at least in these activities there is no strong correlation between the scope or complexity of the regulatory framework and the ideological/ political affiliation of the government. For example, according to the OECD data, Colombia has a more intrusive regulatory framework than Argentina in all of the above-mentioned services, but not necessarily more than in Brazil. Stronger Constraints Although the industrial policy today is much weaker and could use fewer instruments than in the SLI phase, the task before it is more complex. The technological gap with the more advanced economies has remained the same, or has even widened in some cases, and could only be closed with much more investment in science/technology and education. Moreover, the trend toward increasing specialization in natural resources has been strengthened by the rising prices of commodities, weakening the incentives to diversify, modernize, and climb the technological “ladder.” In addition, how is Latin America positioned to conceive and implement selective import substitution policies with export promotion strat- fall 2008 107 egy, the way several Asian countries have done, and continue doing so even today? One heavy constraint is the state. As it stands now, it is in general poorly equipped to implement more complex public policies. The lack of resources, the lack of qualified civil servants, and corruption are some of its main limitations. As a consequence, there are serious obstacles to adopt the policies that were crucial in the process of Asian industrialization, especially those monitoring the performance criteria and enforcing discipline, and the imposition of cooperation on enterprises in a specific sector. A More Active Industrial Policy The shift to a more active industrial policy of the New Left has so far been more rhetoric than reality. In the sphere of rhetoric, the left-of-center governments have announced some policies that represent a significant change as compared to those of the past two decades. There is again the notion that active policies are necessary to transform the productive structure of the economy and to upgrade technologically. However, except for the changes in property rights in certain industries related to the mineral/energy sectors, there is yet not much to be shown. Especially absent have been attempts to create new industries. Initially such absence could be explained by the urgency to face other, more pressing needs by the governments related to macroeconomic stability. However, in many countries today, it simply reflects the weakness of the core of political interests that support it relative to that of other sectors based on natural resources. Such absence is understandable in countries such as Bolivia where there were never any significant political forces to launch a development agenda based on industrialization. The only significant counterexample is Brazil, where the business sector had and continues to have considerable political power to place industrialization as a key lynchpin of the development strategy. It remains to be seen if the industrial policy in the future implemented by other New Left governments will effectively reverse some of the negative trends that Latin America has been experiencing in the past two decades and at the same time avoid the many pitfalls of the SLI period. Latin America urgently needs to exploit better and strengthen the benefits of its comparative advantage on natural-resource intensive products (food, minerals, and other raw materials) and, at the same time, strengthen its manufacturing industry and certain services to build a solid export platform able to pull 108 international journal of political economy the economy into a long-term path of robust expansion. Whether it will have the capacity and time to do so is an open question. Notes 1. In this paper, the term “New Left” is not used in the European sense of the past thirty years but only as a way to identify the left-of-center governments that have arrived to power in the past ten years in Latin America. 2. For further analysis, see Moreno-Brid and Paunovic (2006). 3. On average, more than 400,000 Mexicans migrate abroad annually (Pardinas 2008). Today there are eleven countries in Latin America and the Caribbean with an annual net migratory balance of at least two per thousand (United Nations Development Programme 2007). 4. Latin America has become one of the most violent regions in the world with 25 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, much higher than the world average of 8.8 per 100,000 (United Nations Development Programme 2004). 5. For example, the Country Profile for Bolivia reported in the Economist Intelligence Unit (2008) states “Persistently weak implementation capacity means that the budgeted 65 percent increase in spending (for 2008) will fail to materialize. References Dihel, N., and B. Shepherd. 2005. “Modal Estimates of Service Barriers.” OECD Trade Policy Working Paper No. 51. Paris. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). 2007. Social Panorama 2007. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC-United Nations. ———. 2008. Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean 2007–2008. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC-United Nations. Economist Intelligence Unit. 2008. Country Profile for Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, México, Uruguay and Venezuela. Available at www.eiu. com. Moreno-Brid, J.C., and I. Paunovic. 2006. “The Future of Economic Policy Making by Left-of-Center Governments in Latin America: Old Wine in New Bottles?” In ReVista, Harvard Review of Latin America. Cambridge, MA: David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University. Pardinas, J.E. 2008. “Los Retos de la Migración en México: un espejo de dos caras.” Serie Estudios y Perspectivas, no. 99. Paunovic, I., and J.C. Moreno Brid. 2007. “New Industrial Policies in the New Left of Latin America?” Paper presented at the workshop “Left Turns? Political Parties, Insurgent Movements, and Policies in Latin America,” University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada (May). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2006. Trade and Development Report. Geneva: United Nations. United Nations Development Programme. 2004. Human Development Report. New York: United Nations. ———. 2007. Human Development Report. New York: United Nations.

© Copyright 2026