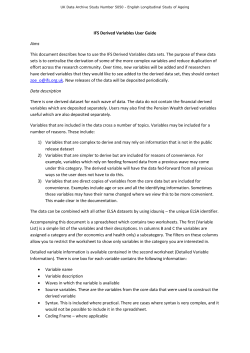

What is Happening with the Government Data Study ∗