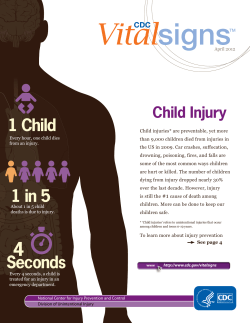

Document 242973