Why Focus on EL Students? NASP CONVENTION 2013 2/10/2013

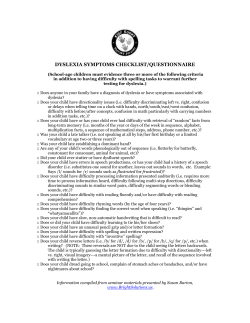

NASP CONVENTION 2013 2/10/2013 Why Focus on EL Students? Growing Numbers of ELs in U.S. Schools From 1997-98 to the 2008-09 school years, the number of EL students increased from 3.5 million to 5.3 million, a 51 percent increase (Batalova & Terrazas, 2010). Uneven Literacy Performance 30% of EL 4th graders reaching basic reading competency compared to 70% for non-EL 29% of EL 8th graders compared to 77% of non-EL MINI SKILLS SESSION: IDENTIFYING ENGLISH LEARNERS WITH DYSLEXIA Dr. Catherine Christo, Megan Sibert, & Natasha Borisov Why Focus on EL Students? cont. The dropout rate for EL students is 15 to 20 percent higher than for the general student population (Sheng, Sheng, & Anderson, 2011). EL students are overrepresented in special education programs (National Council of Teachers of English, 2008). ELL students have lower academic achievement as compared to non-ELL students (Brooks, Adams, & MoritaMullaney, 2010). There is a lack of research, best practice guidelines, or “definitive“ protocol for this population Ethical/Legal Standards NASP Guidelines Ethical/Legal Standards, cont. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing Address issues of language, appropriateness of norms and cultural as well as linguistic differences… IDEA “….findings are not primarily the result of … cultural factors or environmental or economic disadvantage” School psychologists pursue awareness and knowledge of how diversity factors may influence child development, behavior, and school learning. In conducting psychological, educational, or behavioral evaluations or in providing interventions, therapy, counseling, or consultation services, the school psychologist takes into account individual characteristics… Practitioners are obligated to pursue knowledge and understanding of the diverse cultural, linguistic, and experiential backgrounds of students, families,… School psychologists conduct valid and fair assessments. They actively pursue knowledge of the student’s disabilities and developmental, cultural, linguistic, and experiential background,… Presentation Outline 1. Learning Trajectory for EL students 2. Learning to Read 3. Dyslexia Defined 4. Current Assessment Methods 5. Suggestions for Assessment 6. Case Studies 7. Interventions 8. Q&A CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 1 NASP CONVENTION 2013 2/10/2013 Resources What Works Clearinghouse: Reading Rockets http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/publications_reviews.aspx For practice guides and reviews of intervention programs English Language Learners resources Parent friendly Dr. Cristina Griselda Alvarado Learning Trajectory for EL Students www.educationeval.com/.../EvidenceBased_Bil_ed_Programs. Expected Trajectory: BICS vs. CALP L2 Acquisition Stages • Silent Period • Focusing on Comprehension Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) Typically acquired in 1-2 years Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) Typically acquired in 2-7 years Source: Collier, V. P. (1989). How long? A synthesis of research on academic achievement in a second language. TESOL Quarterly, 21(4), 617-624. Stage 1: Preproduction (first 3 months) Stage 2: Early Production (3-6 months) Stage 4: Intermediate Fluency (2-3 years) Stage 3: Speech Emergence (6 months – 2 years) • Improved comprehension • Adequate face-to-face conversational proficiency • More extensive vocabulary • Few grammatical errors • Focusing on comprehension • Using 1-3 word phrases • May be using routine/formulas (e.g., “gimme five”) • • • • Increased comprehension Using simple sentences Expanded vocabulary Continued grammatical errors Source: Rhodes, R.L., Ochoa, S.H.S, Ortiz, O. (2005). Possible Factors Contributing to Delayed L2 Acquisition Mostly, it’s due to: But sometimes, it’s due to: Factors Contributing to Delayed L2 Acquisition Cultural Factors Deficits in Phonological Skills Delayed Second Language Acquisition Family Factors Personal and Intrinsic Factors Environmental Factors L1 Schooling Quality and Quantity Poor self-concept Withdrawn Personality Anxiety Lack of Motivation Traumatic Life Experience Difficult Family Situation Different Cultural Expectations Limited Literacy of Parents in Native Language Poor Instructional Match Unaccepting Teachers and/or School Community CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 2 NASP CONVENTION 2013 2/10/2013 Factors Contributing to Delayed L2 Acquisition, cont. Importance of Home Support… Deficit in phonological skills (both for L1 and L2) is indicative of dyslexia Later exposure to L2 Research shows that children who are exposed to L2 before age 3 have better reading performance than children exposed to L2 in 2nd and 3rd grade. Importance of Native Language Literacy In U.S. schools where all instruction is given in English, EL student with no schooling in their first language take 7-10 years or more to reach age and grade-level norms of their native English-speaking peers. Immigrant students who have had 2-3 years of first language schooling in their home country before they come to the U.S. take at least 5-7 years to reach typical native-speaker performance. Source: Collier, V. (1995). Acquiring a second language for school (electronic version.) Direction in Language and Education, 1(4). Importance of Native Language Literacy cont. Neural mechanisms within parieto-temporal regions of impaired readers in second language learning are similar to that of the impaired reading in a mother language. Whenever possible, look for patterns of language acquisition difficulties in student’s native language. Review records, interview parents, etc. Good to Know… Studies show that students whose primary language is alphabetic with letter-sound correspondence (e.g., Spanish) have an advantage in learning English as opposed to students who speak non-alphabetic languages (e.g., Chinese). CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 3 NASP CONVENTION 2013 2/10/2013 Cross-Language Transfer If students have certain strengths in their L1, and those strengths are known to transfer across languages, then we can expect that the students will develop those proficiencies in their L2 as their L2 proficiency develops Domains of Cross-Linguistic Transfer: Phonological Awareness Syntactic Awareness Functional Awareness Decoding Use of Formal Definitions and Decontextualized Language Learning to Read Basic Assumptions (Regardless of Language Status) Simple model of reading (Tumner and Gough) Decoding Reading Competent reading rests on the development of basic skills Comprehe nsion The “hands and feet of genius” Multiple components of reading must be taught in a systematic, explicit manner that also immerses children in language and text It’s All About the Word Children must learn how visual information is linked to speech – the words and sounds they know. “The first steps in becoming literate, therefore, require acquisition of the system for mapping between print and sound” Ziegler and Goswami, 2006 CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 4 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Well… Maybe Not All 2/10/2013 Word Reading Must Become: Story structure Language Background knowledge Comprehension Fast Accurate Effortless This is true in any language and the crux of the problem in dyslexia across languages. Automatic (Almost) Integrate Multiple Systems Bilingual Environments 1. 2. 3. 4. Visual system Phonology Working memory Language 5. 6. 7. 8. Orthographic Phonological Context Meaning For EL student, each of these areas must be considered! Concepts learned well in one language can be transferred to another Knowledge of phonemes may be absent for English Learners Training helps Children with no phonological problems catch up with their peers in phonological processing in 1 to 2 years National Literacy Panel on Language Minority Children Profiles of both groups with reading problems are very similar Definition of Dyslexia: NICH and IDA Dyslexia Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge. CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 5 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Characteristics of Students With Reading Problems Possible Causes Most reading problems have to do with decoding and spelling Some readers may understand the system but lack fluency Some readers have trouble with comprehension Visual processing Temporal processing Phonological processing Rapid Naming speed Orthographic processing Each of these reading problems require different interventions! Reading and Dyslexia Across Languages Different writing systems Reading and Dyslexia Across Languages Alphabetic Logographic Syllabic Alphabetic languages differ Similar or different alphabet Opaque vs. transparent orthographies For example – Spanish consonants but not vowels 2/10/2013 Directionality of print Can transfer knowledge learned in one language to another Common manifestation is lack of rapid word recognition. Grain size theory Reading and Dyslexia Across Languages In more consistent orthographies dyslexia manifests as problems in fluency rather than accuracy. Children become accurate decoders by first grade Phonological processing, Rapid naming, Orthographic processing Current Methods of Assessment Results have inconsistent results Spanish – all three predicted reading in kindergarteners CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 6 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Factors Contributing to Difficulties when Assessing ELs with LD Who are EL Students? Identifying EL students 2/10/2013 NCLB definition: Typical EL students and EL’s with LD share many characteristics: 1) Age 3-21 2) Enrolled or preparing to enroll in elementary or secondary school 3) Not born in the U.S., native language other than English, comes from an environment where English isn’t the dominant language 4) whose difficulties in speaking, reading, writing, or understanding English may deny him the ability to meet the state’s proficiency level to be successful in an English-only classroom Poor comprehension Difficulty following directions Syntactical and grammatical errors Difficulty completing tasks Poor Motivation Low Self-Esteem Poor Oral Language Skills It has been suggested that linguistic diversity may increase assessment errors and reduce the reliability of assessments Lack of teachers trained in bilingual and multicultural education to meet and assess EL students’ needs Mistaking basic interpersonal communication skills (BICS) for cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP) Assessment in English Pro’s: Con’s: Accommodations can be made (to test itself or to test procedure) to provide a more valid picture of the ELL student’s abilities: Provides information about the student’s level of functioning/ability in an English-speaking environment Student’s may not thoroughly understand task instructions or particular test items due to limited English proficiency Compromises test validity: Student not represented in the norm group Changing/simplifying language to improve understanding of test instructions breaks standardization Students demonstrate slower processing speeds and are more easily distracted during assessments conducted in a language with which they are less familiar Assessment in English Assessment in Native Language Checklist of Test Accommodations Before Conducting the Test: Make sure that the student has had experience with content or tasks assessed by the test Modify linguistic complexity and text direction Prepare additional example items/tasks During the Test: Allow student to label items in receptive vocabulary tests to determine appropriateness of stimuli Ask student to identify actual objects or items if they have limited experience with books and pictures Use additional demonstration items Record all responses and prompts Test beyond the ceiling Provide additional time to respond/extra testing time Reword or expand instructions Provide visual supports Provide dictionaries Read questions and explanations aloud (in English) Put written answers directly in test booklet (modified from Szu-Yin & Flores, 2011) Pro’s: May provide a more accurate inventory of student’s knowledge and skills Interpreters can be utilized to facilitate testing if psych doesn’t speak student’s native language Con’s: Language-specific assessment for each and every student are not available If they are unfamiliar with the educational context, using interpreters may compromise test validity CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 7 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Current Methods of Identifying/Assessing SLD/Dyslexia Nonverbal Assessment Pro’s: IQ-Achievement Discrepancy Attempts to eliminate language proficiency as a factor in the assessment May provide a better/more accurate estimate of student’s cognitive abilities Strengths of this method: Con’s 2/10/2013 Weaknesses of this method: Often does not fully eliminate language Offers a limited perspective of a student’s academic potential Fails to provide information about linguistic proficiency in student’s native language or in English Widely used and understood Provides fairly clear-cut criteria for which students have and do not have SLD/Dyslexia Uses norm or criterion-referenced standardized tests IQ scores based on tests administered in English lack validity and reliably for bilingual children whose language proficiency in English is still developing IQ is likely to be underestimated when tests are given in English, lessening likelihood of identification of SLD in ELL students Gap between scores of immigrant and indigenous children on IQ tests becomes smaller the longer the immigrant student has been in the English-speaking country (Ashby et al.) Content of IQ tests may lack any overlap with content covered in or important to the academic context Current Methods of Identifying/Assessing SLD/Dyslexia RTI/CBM Strengths: Weaknesses: Current Methods of Identifying/Assessing SLD/Dyslexia CBM- continued Strengths: CBM reading measures have been found to be a sensitive measure of reading progress for bilingual Hispanic students Direct link between assessment and instruction Found to be very useful for native English-speaking students Data-based decision making about placement Weaknesses: Very little research done regarding use of CBM specifically with bilingual students Relationship between reading fluency and reading proficiency in ELL’s learning to read in English is not clear Curriculum being taught is not necessarily culturally unbiased or sensitive Uses multiple measures of functioning/ability (CBM) and monitors students to ensure they are progressing or are identified as needing more support Focuses more on supporting students’ needs and less on labeling their challenges Ensures appropriate and effective curricula are being implemented with fidelity and integrity Doesn’t consider many ecological variables Doesn’t provide scientifically based research on the varying population that RTI is purported to benefit Current Methods of Identifying/Assessing SLD/Dyslexia Patterns of Strengths and Weaknesses Strengths: Focuses on individual student’s performance pattern Can interpret pattern of scores in comparison to typical pattern of English Learners Provides information that may be helpful in designing interventions Weaknesses: Doesn’t consider many ecological variables Limits of using cognitive processing measures with English Learners CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 8 NASP CONVENTION 2013 When Should You Refer EL’s for Special Ed? 2/10/2013 Questions to Consider Depends on the system your school follows: RTI, PSW or discrepancy approach? Are the instruments being used appropriate for the student? Will a variety of tests, instruments, or procedures be used to determine if a child is a child with a disability? Will actual test scores be provided or will the test results be reported descriptively? Will the student be evaluated in his or her native language? Why or why not? Are bilingual personnel available to complete the evaluation? If there are no bilingual personnel available, will interpreters be used to evaluate the child? Will the student be evaluated in the language of instruction? Has the assessment process been explained to the parents in their native language if necessary? Source: http://www.sde.ct.gov/sde/lib/sde/ pdf/curriculum/bilingual/CAPELL_SP ED_resource_guide.pdf Recommendations for Best Practice Assess students in both native language and English Thorough analysis of language proficiency using a broad range of test results and observation (multiple data sources) Provide information on: best educational placement for the student type of instruction that would be most beneficial the point at which student will be ready to transition from bilingual education to English-only education Assessment and Diagnosis Recommendations for Best Practice Use of observations and interviews in multiple settings, times, and events Assessment of portfolios, work samples, projects, criterion-referenced tests, informal reading inventories, and language samples. (APA, 1985; IDEA, 1990, 1997) Best Practice Guidelines (Cline, 1995) The active involvement of EL and bilingual support teachers at every stage Recording and reviewing information on a student’s knowledge and use of native language and of English Setting and reviewing of specific educational goals that include language and cultural needs Arrangement of appropriate language provision Investigation of social, cultural, and language isolation and peer harassment Using interpreter when appropriate Placing student performance in context CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 9 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Multidimensional Assessment Model for Bilingual Individuals (MAMBI) Models for Assessing CLD/Bilingual Students Ortiz, Ochoa, Dynda (2012) Contemporary Intellectual Assessment A grid that provides nine profiles for a practitioner to choose from and takes into consideration 3 major variables about the student: MAMBI C-LIM Current grade Type of educational program Proficiency in both L1 and L2 Guajardo Alvarado www.educationeval.com Once these variables are accounted for, the practitioner is left with the method of evaluation most likely to yield valid results: Best Practices in Special Education Evaluation of Students Who are Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Bilingual Special Education Eval … Woodcock Test Nonverbal Assessment Assessment primarily in L1 Assessment primarily in L2 Bilingual assessment both in L1 and L2 2013 Cultural and Linguistic Classification of Tests Alvarado’s 4 Steps to Bilingual Special Education Evaluation Available in Flanagan, Ortiz, and Alfonso: Essentials of Cross Battery Assessment PATTERN OF EXPECTED PERFORMANCE OF CULTURALLY AND LINGUISTICALLY DIVERSE CHILDREN DEGREE OF LINGUISTIC DEMAND LOW MODERATE 1. HIGH LOW PERFORMANCE LEAST AFFECTED INCREASING EFFECT OF LANGUAGE DIFFERENCE MODERATE 3. HIGH DEGREE OF CULTURAL LOADING 2. 4. INCREASING EFFECT OF CULTURAL DIFFERENCE PERFORMANCE MOST AFFECTED (COMBINED EFFECT OF CULTURE & LANGUAGE DIFFERENCES) Gathering of student information Oral language proficiency and dominance testing Achievement testing Cognitive testing The language or languages of each step is dictated by the individual student’s language exposure, language dominance, and academic background and by the objective of the assessment. Informal Ways to Assess Language Dominance Determining Language Dominance 2/10/2013 Alvarado’s model for determining language dominance: Using a test that has two language forms that have been statistically equated in order to allow comparison of abilities and skills between those two languages. Two steps are proposed: 1: the core language of the cognitive battery is determined on the basis of the student’s dominant language 2: the appropriate scale is selected on the basis of the student’s language status in his/her dominant language In the Woodcock tests, the Batería III COG is statistically equated to the WJ III COG. Likewise the Batería III APROV is statistically equated to the WJ III ACH. Language student prefers talking in Which language produces better phrasing Speech therapists can test What movies do they watch (English or Spanish) Friends on playground CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 10 NASP CONVENTION 2013 2/10/2013 Current Academic Variables Considering Contexts, Academic Variables, & Processing Context: Culture Processing Context: Language Context Ethnicity Birthplace Number of years in the U.S. Parent Education (where, what level, quality, in L1/L2) Context: Education Context Impact of poverty –environmental and neurological Dyslexia may manifest in one language and not another Understanding of text structure Nature of first language may impact how quickly students learn second Context Proficiency in L1 & L2 Student’s primary/dominant language CELDT scores Language(s) spoken at home Primary language of parent(s) and sibling(s) Parent language proficiency in L1 & L2 Exposure to English School Family Media Cultural/Linguistic Factors Context Schooling in another country Duration Quality Years of formal school In L1 & L2 Curriculum used EL program or other special education/intervention program Educational progress Previous work samples Prior language proficiency levels/CELDT scores Context Phonetic may be easier to transfer Language loss for native language Semi-lingualism Process and conditions of learning second language CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 11 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Current Academic Variables: Teacher/Classroom/School Curriculum Teacher training in teaching EL students Teaching strategies used Direct & systematic Use of visuals, concrete objects Opportunities for hands-on learning Scaffolding techniques Varied instructional grouping Interventions Frustrational/instructio nal/mastery levels Progress monitoring data Research/evidencebased? Rate of improvement Minutes of ELD per day Language use in classroom Current Academic Variables: Student Variables Current level of performance (compare to EL & non-EL peers) Math ELA Peer groups, quality of peer interaction, behavior Classrooms Playground Difficulty in determining: benchmarks expectations appropriate growth Lack of growth can be due to variety of factors, such as: Language SES Instruction IDEA 2004 explicit on this As defined in NCLB Contain the 5 areas noted in National Reading Panel Has child had high quality, research based interventions? School history Data from an RtI model Types of interventions Progress made Sources of information History Direct observations Performance of other students Interviews with teachers/parents to further clarify problem How CBM Can Help EL Students Current Academic Variables Determine whether instructional programs are addressing needs of EL population as a whole Inform instructional decisions for struggling EL readers Compare target students to peers Using CBM with ELs Current Academic Variables Current Academic Variables Has child had adequate reading instruction. Problems With CBM and ELs Current Academic Variables Home History Interaction with adults School Home History Personality Rule Out Lack of Instruction Current Academic Variables 2/10/2013 Current Academic Variables Used to: Screen for students at risk of learning difficulties Monitor progress of all students Monitor progress of selected students Determine whether instruction/intervention is effective Making special education decisions CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 12 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Using CBM with ELs DIBELS found to better predict low risk than at risk Useful but need more research Relationship between oral reading fluency and comprehension ELs have different growth rates than non-ELs Start lower so even with same slope don’t catch up Fluency probes over-predict reading scores Have weaker relationship with future reading than for non-EL Current Academic Variables More extraneous variables that can lead to measurement error Reading Components and Processing Processing National Reading Panel Phonemic Awareness in L1 and L2 Phonics in L1 and L2 Fluency Vocabulary Comprehension In comparison to peers In comparison to self Appropriate instruction/intervention Other processes related to reading Lack of research on effective intervention Targeted intervention Phonological Processing Most common for English only Associated with reading deficits in most languages but strength of relationship varies Phonological processing in English predicts reading for EL reading disabled. Difficult to determine directionality and causality Cross language impact Spanish phonological processing linked to English reading Rapid naming Working memory Oral Language Weakness in Cognitive Process Related to Reading Current Academic Variables Kindergarten phonemic segmentation fluency poor predictor of later decoding Oral reading fluency may be better than maze fluency for predicting later comprehension Diversity of ELs IDELS: Spanish version of DIBELS AIMSweb Spanish reading How to determine underachievement Using CBM with ELs Classifies EL at risk better than non-EL RTI with ELs Current Academic Variables 2/10/2013 New Directions Processing Processing Basing assessment in phonological skills Less culturally biased than IQ testing Phonological processing skills relevant to alphabetic literacy can be developed by exposure to any language Phonology is a surface feature of language and “native-like” familiarity in the phonology of a new language should be developed more quickly than CALP skills (2 years vs. 5-7 years) (Frederickson and Frith, 1998) CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 13 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Cognitive Processes Swanson et al (2012) ELs and bilinguals w/w/o RD Short term memory (core phonological loop) problem or Working memory deficit impacting controlled attention Spanish and English Naming speed, Orthographic processing Working memory Consider Spanish working memory and word reading English phonological processing and naming speed Some in Spanish May also be Available Tests WJ Bateria Phonological processing Long term storage and retrieval Some working memory Some rapid naming TOPPS (researcher developed version of CTOPP) CELF WISC IV TAPS Processing Naming speed – English Strongest measures Reading disabled students who are EL and bilingual have similar cognitive profiles Phonological processing Cognitive Processes Processing 2/10/2013 CHC factors, Berninger (PAL II) Processing DAS II ROWPVT, EOWPVT Woodcock Munoz Language Survey-R BVAT-NU Case Example Ling-lee, 11 years, 6th grade Adopted from China at age 10 years She lives with her parents and younger sister, who is also from China Has low vision and she began to wear glasses after coming to the U.S. Parents have limited information about her early health history Currently in good health with the exception of seasonal allergies Problem behaviors when Ling-lee first arrived are mostly gone and she does well socially Attends Chinese school and hip-hop dance Ling-lee states likes math best – also language arts because it makes you think and learns something new every day. Likes social studies least but learns interesting things - doesn’t get it sometimes. Reasons for Referral Does Ling-lee have dyslexia? Does Ling-lee have dyscalculia? How can the school and her parents best help Linglee to learn? CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 14 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Educational History Previous Evaluations Attended school through 2nd grade in China; picked up English quickly upon coming to the United States. Chinese School teacher said that her skills in reading and writing in Mandarin where at the 4th grade level. Currently she is receiving A’s and B’s in her classes at Chinese School. Attended private school for 4th grade. She began at Ivy in 5th and is currently in 6th Outside tutoring in Barton based reading and math Able to decode but struggles with comprehension (mother notes in both oral and written) Problems with directionality in math and reading CST 2011 Far Below Basic; CELDT scores Early Intermediate in Listening, Speaking and Reading and Beginning in writing. Special Education evaluation on 10/2011 Placed due to academic underachievement in reading, writing and math and processing disorder in attention. Goals in math, reading, written language Academic: WJ-III (10/2011) Spelling weakest Cognitive: K-ABC II (4/2010) Long-Term Retrieval = Average All other scores in the Below Average range Verbal =16th percentile; Visual = 27th percentile; Attention/Concentration = below average TAPS 3 Phonological Processing, Visual Motor Skills, & Memory = Average Language Understanding very weak BASC-2 WISC IV WRAML 2 Word Identification = 14th percentile Fluency & Reading Comprehension = Well Below Average Written Language = Below Average Math Calculations & Math Fluency = Average Range Reading SS=85, 16th percentile; VCI = 3rd percentile; WM = 4th percentile; PS = 24th percentile Mother: Clinically Significant Hyperactivity, Conduct Problems, Depression Teacher: No clinically significant areas Assessment Results Behavior During Testing 2/10/2013 Friendly, conversed with the examiner regarding topics such as vacations, friends and family pets… responded appropriately in conversations but did little reciprocal questioning or expansion on topics. Generally Ling-lee worked quickly… difference between her response pattern, depending on the area being assessed… math… consider and monitor her response much more than in written language. Ling-lee did not display signs of inattention as has been noted in previous testing, though she was eager to complete the testing so that she could do other things. Occasionally language issues were noted; for example, in asking for repeated instructions when the instructions were complex. KAUFMAN TEST OF EDUCATIONAL ACHIEEMENT II Subtest Score Percentile Cluster/Subtest (mean=100) READING Letter and Word Recognition WRITTEN LANGUAGE Written Expression READING RELATED SUBTESTS Nonsense Word Decoding TEST OF WORD READING EFFICIENCY Standard Score (Range) Sight Word 92 Efficiency Phonemic Decoding Efficiency 90 92 30th 61 <1st 92 30th GRAY ORAL READING TEST 5 Standard Percentile Score Rate 7 16th Accuracy 8 25th Fluency 7 16th Composite Comprehension 16th 7 PROCESS ASSESSMENT OF THE LEARNER – II (PAL-II) Skills Scaled Score Composite/Subtest Phonological Pseudoword Fluency 8 Pseudoword accuracy 7 Morphological Decoding Find the Fixes 9 Morph Decoding Fluency 6 Morph. Decoding Accuracy 7 Related Processes Composite/Subtest Orthographic Coding COMP. Receptive Expressive Phonological Coding Syllables Phonemes Rimes Silent Reading Fluency Morphological/syntactic Coding 4 Are They Related Does It Fit Sentence Structure Rapid Automatic Naming/ Switching Total Letters Letter groups Words Verbal Working Memory Letters Words Sentences/Listening Sentences/Writing 10 3 2 11 Sentence Sense Accuracy Sentence Sense Fluency Orthographic Spelling Word Choice Accuracy 4 3 12 Word Choice Fluency 12 Scaled Score 8 9 8 5 5 5 7 11 12 9 6 3 9 10 Assessment Results, cont. Cluster/Subtest BASIC CONCEPTS Numeration Algebra Geometry Measurement Data analysis OPERATIONS Mental Computation Addition/Subtraction Multiplication/Division APPLICATIONS Foundations of Problem Solving Applied Problem Solving KEYMATH 3 Standard Score Scaled Score Percentile (mean=100) (mean=10) 7TH 78 (73-82) 8 7 6 6 6 30th 92 (86-98) 10 9 8 7th 78 (69-97) 7 5 CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 15 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Carlos, 8 years, 3rd grade Background Information Latino boy, resides in San Francisco with his mother, father, twin sister, and older brother (20) Hearing and vision are within normal limits. Carlos was born in San Francisco to parents of Mexican descent. Spanish is primary language, though some English is spoken in the home, as well. Primary language of instruction is Spanish, though he receives some instruction in English, and he often prefers to speak English in informal conversation. Carlos reports that his English is “not really good,” and that Spanish is all he speaks at home. Assessment Results: DAS-II Composite/Cluster Standard Score Special Nonverbal Composite 98 45th Average 97 42nd Average Nonverbal Reasoning Spatial Cluster Percentile T-Score Descriptor 50th 100 Clusters/Subtests Average Percentile Descriptor Nonverbal Reasoning Cluster Matrices 48 42nd Average Sequential & Quantitative Reasoning 48 42nd Average 50 54th Average 51 54th Average Spatial Cluster Subtests Recall of Designs Pattern Construction Test of Auditory Processing Skills-3 (TAPS 3) Index Standard Score Percentile Descriptor Phonologic 90 25th Average Memory 83 13th Bilingual Verbal Ability TestsNormative Update (BVAT-NU) Cluster/Subtest Standard Score Percentile Descriptor Bilingual Verbal Ability 89 23rd Below Average English Language Proficiency 86 18th Below Average Picture Vocabulary 86 17th Below Average Oral Vocabulary 95 37th Average 88 21st Verbal Analogies Below Average *Norms based on age Test of Auditory Processing Skills 3: Spanish Bilingual Edition (TAPS-3: SBE) Percentile Subtest Scaled Score Percentile Word Memory 9 37th Sentence Memory 7 16th 9 37th Memory Phonologic Word Discrimination 9 37th Phonological Segmentation 8 25th Phonological Blending 7 16th 4 2nd Cohesion Auditory Comprehension Carlos is currently a 3rd grade student at Elementary School in San Francisco, in the Bilingual Pathway. Most academic instruction is delivered in Spanish Receives daily English Language Development (ELD) support. His teacher reports that his reading, writing, and math skills are improving, but that he continues to require additional support. He received speech/language therapy in the past, but was exited from those services following his last triennial evaluation. Attends the afterschool program. Described as a very sweet, motivated, and cooperative young boy. His teacher states that Carlos is very intelligent, respectful, and has high self-esteem. Below Average Scaled Scores Subtest 2/10/2013 Cohesion Memory Number Memory Forward 7 16th Number Memory Reversed 9 37th Word Memory 2 <1st Sentence Memory 8 25th CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 16 NASP CONVENTION 2013 Test of Visual Perceptual Skills 3 (TVPS-3) 2/10/2013 Woodcock Johnson III (WJIII)-Test of Achievement (Norms based on age) Cluster Standard Score Percentile Descriptor Overall 76 5th Low Basic Processes 80 9th Below Average Subtests SS/Percentile Sequencing 65 1st Very Low Complex Processes 75 5th Story Recall 86/18th Picture Vocabulary 71/3rd Understanding Directions 73/3rd Oral Comprehension 93/31st Writing Fluency 88/21st Writing Samples 89/23rd Letter-Word Identification 88/21st Word Attack 99/48th Passage Comprehension 77/6th Reading Vocabulary 87/19th Calculation 121/92nd Math Fluency 96/39th Applied Problems 79/8th Quantitative Concepts 91/27th Reading Fluency 91/28th Low Scaled Scores Cluster Percentile Basic Processes VMI: 112, 79th Percentile Visual Discrimination 5 5th Visual Memory 5 5th Spatial Relations 8 25th Form Constancy 6 9th 3 1st Figure Ground 5 5th Visual Closure 5 5th Sequencing Sequential memory Complex Processes Cluster areas for determining Specific Learning Disability according to IDEA MATH REASONING 83/12th ORAL EXPRESSION 71/3rd LISTENING COMPREHENSION 80/10th READING FLUENCY 91/28th MATH CALCULATION 114/83rd READING COMPREHENSION 77/6th WRITTEN EXPRESSION READING FLUENCY 87/20th 91/28th BASIC READING SKILLS 93/31st Bateria III Pruebas De Aprovechamiento (Norms based on age) Bateria III Tests of Achievement: Bateria III Cluster areas for determining Specific Learning Disability according to IDEA Rememoracion de cuentos 87/20th Vocabulario sobre dibujos 66/1st EXPRESION ORAL 68/2nd Comprension de indicaciones 62/1st Comprension Oral 73/3rd COMPRENSION AUDITIVA 59/<1st Fluidez en la escritura 87/19th Muestras de redaccion 98/45th EXPRESION ESCRITA 92/31st Identificacion de letras y palabras 111/77th Analisis de palabras 109/73rd DESTREZAS BASICAS en LECTURA 112/78th Comprension de textos 87/19th Vocabulario de lectura 81/11th COMPRENSION de LECTURA 80/9th Problemas Aplicados -Conceptos cuantitativos 88/22nd RAZONAMIENTO en MATEMATICAS -Fluidez en la lectura 47 FLUIDEZ en la LECTURA 47 Interventions The following reading interventions are recommended by What Works Clearinghouse for use with ELL students: Enhanced Proactive Reading Read Well SRA Reading Mastery/SRA Corrective Reading Interventions Interventions AIM for the BESt: Assessment and Intervention Model for the Bilingual Exceptional Student Common elements in the above intervention programs: Incorporates pre-referral intervention, assessment, and intervention strategies Uses nonbiased measures Aims to improve academic performance for culturally and linguistically diverse students and aims to reduce inappropriate referrals to special education formed a central aspect of daily reading instruction between 30 and 50 minutes to implement per day intensive small-group instruction following the principles of direct and explicit instruction in the core areas of reading extensive training of the teachers and interventionists How? Use of instructional strategies proven to be effective with language-minority students Allows teachers flexibility to modify instruction for struggling students Supports teachers with a team of professionals Uses CBM and criterion-referenced tests to assess in addition to standardized test data Model holds promise for improving educational services provided to limited English-proficient students(Ortiz et al., 1991) CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 17 NASP CONVENTION 2013 References References, cont. Alvarado, C.G. (n.d.). Bilingual special education evaluation of culturally and linguistically diverse individuals using Woodcock tests. Ashby, B., Morrison, A. & Butcher, H.J. (1970). The abilities and attainments of immigrant children. Research in Education, 4, 73-80. Ascher, C. (1991). Testing Bilingual Students. Do We Speak the Same Language? PTA Today, 16(5), 7-9. Baker, S. K., & Good, R. (1994). Curriculum-Based Measurement Reading with Bilingual Hispanic Students: A Validation Study with Second-Grade Students. Batalova, J., & Terrazas, A. (2010). Frequently requested statistics on immigrants and immigration in the United States. Retrieved on October 21, 2011 from http://www.migrationinformation.org/USFocus/display.cfm?ID=818#1a Becker, H., & Goldstein, S. (2011). Connecticut administrators of programs for English language learners: English language learnes and special education: A resource handbook. Retrieved from CAPELL_SPED_resource_guide.pdf. Brooks, K., Adams, S. R., & Morita-Mullaney, T. (2010). Creating inclusive learning communities for ELL students: Transforming school principals' perspectives. Theory Into Practice, 49(2), 145-151. Christo, C. Crosby, E. Zoraya, M. (In press). Response to Intervention and Assessment of the Bilingual Child. In A. Clinton (Ed.) Integrated Assessment of the Bilingual Child. APA Publications Clinton, A. (in press) Semi-lingualism: What neuroscience tells us about the complexities of assessing the bilingual child from low socio-economic backgrounds. In A. Clinton (Ed.) Integrated Assessment of the Bilingual Child. APA Publications Cline, T. (1998). The assessment of special educational needs for bilingual children. British journal of Special Education, 25 (4), 159-163. Collier, V. (1995). Acquiring a second language for school (electronic version.) Direction in Language and Education, 1(4). Chu, S., & Flores, S. (2011). Assessment of English Language Learners with Learning Disabilities. Clearing House: A Journal Of Educational Strategies, Issues And Ideas, 84(6), 244-248. Dixon, L. Q., Chuang, H.-K., & Quiroz, B. (2012). English phonological awareness in bilinguals: a crosslinguistic study of Tamil, Malay and Chinese English-language learners. [Article]. Journal of Research in Reading, 35(4), 372-392. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9817.2010.01471.x de Ramírez, R. D., & Shapiro, E. S. (2006). Curriculum-Based Measurement and the Evaluation of Reading Skills of Spanish-Speaking English Language Learners in Bilingual Education Classrooms. [Article]. School Psychology Review, 35(3), 356-369 Figueroa, R. A. (1989). Psychological Testing of Linguistic-Minority Students: Knowledge Gaps and Regulations. Exceptional Children, 56(2), 145-52. Frederickson, N.L. & Frith, U. (1998). Identifying dyslexia in bilingual children: A phonological approach with Inner London Sylheti speakers. Dyslexia, 4, 119-131. Linan-Thompson, S., & Ortiz, A. A. (2009). Response to Intervention and English-Language Learners: Instructional and Assessment Considerations. [Article]. Seminars in Speech & Language, 30(2), 105-120. Linan-Thompson, S., Cirino, P. T., & Vaughn, S. (2007). Determining English learners response to intervention: Questions and some answers. Learning Disability Quarterly, 30(3), 185-195. Cline T (1998) The assessment of special educational needs for bilingual children British journal of Special References, cont. 2/10/2013 References, cont. National Council of Teachers of English. (2008). English language learners: A policy brief. Retrieved on October 21, 2011 from http://www.ncte.org/library/ NCTEFiles/Resources/PolicyResearch/ELLResearchBrief.pdf O'Bryon, E. C., & Rogers, M. R. (2010). Bilingual school psychologists' assessment practices with English language learners. [Article]. Psychology in the Schools, 47(10), 1018-1034. doi: 10.1002/pits.20521 Ortiz, A. A., Robertson, P. M., Wilkinson, C. Y., Liu, Y.-J., McGhee, B. D., & Kushner, M. I. (2011). The Role of Bilingual Education Teachers in Preventing Inappropriate Referrals of ELLs to Special Education: Implications for Response to Intervention. [Article]. Bilingual Research Journal, 34(3), 316-333. doi: 10.1080/15235882.2011.628608 Ortiz, S. O., Ochoa, S. H., & Dynda, A. M. (2012). Testing with culturally and linguistically diverse populations: Moving beyond the verbal-performance dichotomy into evidence-based practice. In Flanagan, D. P. & Harrison, P. L., (3rd Edition), Contemporary Intellectual Assessment (p. 526-552). New York, NY: Guildford Press. Ortiz, A. A., Wilkinson, C. Y., Robertson-Courtney, P., & Kushner, M. I. (2006). Considerations in Implementing Intervention Assistance Teams to Support English Language Learners. Remedial And Special Education, 27(1), 5363. Ortiz, A. A., & Yates, J. R. (2001). A Framework for Serving English Language Learners with Disabilities. Journal Of Special Education Leadership, 14(2), 72-80. Petitto, L.A. (2009). New discoveries from the bilingual brain and mind across the life span: Implications for education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 3, 185-197. Pollard-Durodola, P., Cárdenas-Hagan, E., Tong, F. (In press). Implications of bilingualism in reading assessment. . In A. Clinton (Ed.) Integrated Assessment of the Bilingual Child. APA Publications Ramus F, Rosen S, Dakin SC, Day BL, Castellote JM, White S, Frith U. (2003). Theories of developmental dyslexia: insights from a multiple case study of dyslexic adults. Brain, 126, 841–865. Rhodes, R.L., Ochoa, S.H.S, Ortiz, O. (2005). 'Bilingual Education and Second-Language Acquisition'. In Assessing Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students: A Practical Guide. 1st ed. New York: The Guildford Press. Roseberry-McKibbin, C., & O'Hanlon, L. (2005). Nonbiased Assessment of English Language Learners: A Tutorial. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 26(3), 178-185. Sandberg, K. L., & Reschly, A. L. (2011). English Learners: Challenges in Assessment and the Promise of Curriculum-Based Measurement. [Article]. Remedial & Special Education, 32(2), 144-154. doi: 10.1177/0741932510361260 Swanson, H. L., Orosco, M. J., & Lussier, C. M. (2012). Cognition and Literacy in English Language Learners at Risk for Reading Disabilities. [Article]. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 202-320. doi: 10.1037/a0026225 Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE, Pugh KR, Mencl WE, Fulbright RK, Skudlarski P, Todd-Constable R, Marchione KE, Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Gore JC. (2002). Disruption of posterior brain systems for reading in children with developmental dyslexia. Biological Psychiatry, 52,101–110 Sheng, Z., Sheng, Y., & Anderson, C. J. (2011). Dropping out of school among ELL students: Implications to schools and teacher education. Clearing House, 84(3), 98-103.U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Census population profile maps. Retrieved on October 21, 2011 from http://www.census.gov/geo/www/maps/ 2010_census_profile_maps/census_profile_2010_main.html Wilda, L.-R., Ochoa, S. H., & Parker, R. (2006). The Crosslinguistic Role of Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency on Reading Growth in Spanish and English. [Article]. Bilingual Research Journal, 30(1), 87-106 You, H., Gaab, N., Wei, N., Cheng-Lai, A., Wang, Z., Jian, J., & Ding, G. (2011). Neural deficits in second language reading: fMRI evidence from Chinese children with English reading impairment. Neuroimage, 57(3), 760-770. CHRISTO, BORISOV, SIBERT 18

© Copyright 2026