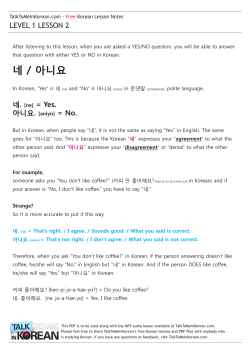

Document 246287