Why do we all need antibiotic stewardship as a matter of urgency?

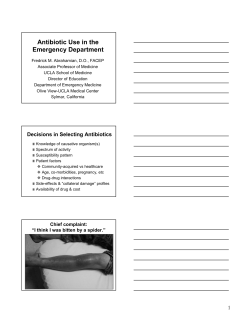

Why do we all need antibiotic Controversies in the treatment of stewardship as a matter of MDR GNB urgency? Adrian Brink Clinical Microbiologist, Ampath National Laboratory Services, Milpark Hospital, Johannesburg Scope of the presentation • Introduction • Treating serious ESBL infections with ertapenem, cefepime or β-lactam/ β-lactamase inhibitors • Combination vs monotherapy: • Combination vs monotherapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia • Adding rifampicin to colistin for the treatment of serious XDR Acinetobacter baumannii infections • Continuous infusion or extended infusion of β-lactams vs intermittent infusion • Conclusions Introduction Introduction Introduction • Many daily practices regarding antibiotic choice, antibiotic combinations, dosing regimens and alternative administration schedules, occur off-label and without sufficient evidence emanating from prospective, randomized, controlled trials • This is particular true in the case of empiric or directed therapy for MDR Gram-negatives and more so in the ICU setting • For example, no prospective, randomized, controlled trials have ever been conducted analyzing the preferred therapeutic management of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections. TreatingIntroduction serious ESBL infections with ertapenem, cefepime or βlactam/ β-lactamase inhibitors? Treatment of serious ESBL infections • Few small retrospective trials have demonstrated the relative superiority of carbapenems over other agents and included imipenem and meropenem, which have been the preferred agents for bacteraemic ESBL infections (although their antipseudomonal activity is unnecessary) • Summarized by a meta-analysis of 21 studies involving 1584 patients where carbapenems had a lower mortality vs. nonBL/BLI (cephalosporins/quinolones) as definitive or empirical Rx (RR 0.60 95% CI 0.33-0.77) Vardakas et al. JAC 2012; 67:2793 Collins et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:2173-77 Ertapenem: Treatment of serious ESBL infections • Collins et al, recently aimed to compare the efficacies of ertapenem and imipenem/meropenem for the treatment of bloodstream infections due to ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (n=261) • Outcomes were equivalent between patients treated with ertapenem and those treated with group 2 carbapenems (mortality rates of 6% and 18%, respectively; P=0.18). Collins et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:2173-77 Ertapenem: Treatment of serious ESBL infections Collins et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:2173-77 Ertapenem: Treatment of serious ESBL infections • Patients receiving ertapenem were significantly more likely to have bacteremia from a urinary source (P=0.01) and to have E. coli ESBL infection (P= 0.001). • The length of hospital stay prior to ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolation was shorter in patients receiving ertapenem (P = 0.002), and patients receiving ertapenem were less likely to have been in the ICU prior to culture (P=0.005) • Severe levels of sepsis, per SIRS criteria, were significantly less common in the ertapenem-treated group than in the group 2 carbapenem-treated group (10% versus 33.3%, respectively; OR 0.23; P= 0.002) • In a multivariate analysis, the type of carbapenem (group 1 versus group 2) was not associated with increased mortality (adjusted OR 0.26; P= 0.12). • Adjusted predictors of mortality included the severity of sepsis (P< 0.005) and the McCabe score at admission. • After controlling for a propensity score of receiving ertapenem consolidative therapy, ertapenem was not associated with increased risk for death (OR 0.50 [95% CI 0.12 to 2.1]; P = 0.34). • In terms of AS efforts, ertapenem should be considered as an option for the Rx of bactaraemic ESBL-infections Collins et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:2173-77 Cefepime: Treatment of serious ESBL infections • A retrospective study of monomicrobial bacteremia caused by ESBL producers at 2 medical centers between May 2002 and August 2007 was performed (n=178) • The patients definitively treated with in vitro active cefepime (cases) were compared with those treated with a carbapenem (controls) in a propensity score–matched analysis to assess therapeutic effectiveness. The 30-day crude mortality was the primary endpoint. • Multivariate regression revealed that a critical illness with a Pitt bacteremia score ≥4 points (OR 5.4; 95% CI, 1.4–20.9; P = .016), a rapidly fatal underlying disease (OR 4.4; 95% CI, 1.5– 12.6; P = .006), and definitive cefepime therapy (OR 9.9; 95% CI, 2.8–31.9; P < .001) were independently associated with 30day crude mortality. Lee et al. Clin Infect Dis 2013:56:488-495 Cefepime: Treatment of serious ESBL infections Mortality (%) Based on the current CLSI susceptible breakpoint of cefepime (MIC ≤8 µg/mL), cefepime definitive therapy is inferior to carbapenem therapy in treating patients with so-called cefepimesusceptible ESBL-producer bacteremia (except if MIC ≤ 1mg/L). Cefepime MIC level (μg/mL) Figure 1. Mortality rates of 3 subgroups of patients who receive cefepime therapy (n = 33) by the cefepime minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) βL/βL-inhibitors: Treatment of serious ESBL infections • Recently, a post hoc analysis of patients with bloodstream infections due to ESBL-producing E coli from 6 published prospective cohorts, provided insight into the potential role of βL/βL-inhibitors. • Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid [AMC] and piperacillin-tazobactam [PTZ]) or carbapenem were compared in 2 cohorts: the empirical therapy cohort (ETC, n=103) and the definitive therapy cohort (DTC, n=174). • Mortality rates at day 30 for those treated with BLBLI versus carbapenems were 9.7% versus 19.4% for the ETC and 9.3% versus 16.7% for the DTC, respectively (P > 0.2, log-rank test). Rodriquez-Bano et al.. Clin Infect Dis 2012:54:167-74 βL/βL-inhibitors: Treatment of serious ESBL infections • After adjustment for confounders, no association was found between either empirical therapy with BLBLI (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], .29–4.40; P = .84) or definitive therapy (adjusted HR, 0.76; 95% CI, .28– 2.07; P= .5) and increased mortality. • The results suggest that AMC and PTZ are suitable alternatives to carbapenems for treating patients with BSIs due to ESBL-EC if active in vitro and would be particularly useful as directed therapy, in a carbapenem-conserving program • This was confirmed by Peralta et al, in a multicentre cohort study evaluating the impact of empirical treatment in ESBLproducing E. coli and Klebsiella spp. bacteremia. Rodriquez-Bano et al.. Clin Infect Dis 2012:54:167-74 Peralta et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2012, 12:245 βL/βL-inhibitors: Treatment of serious ESBL infections • Mortality at 30 days in patients empirically treated with pip/tazo 4.5 grams q 6 hours • 4.5% (1/22) if the MIC was <4 mg/L • 23% (3/13) if the MIC was >4 mg/L Rodriquez-Bano et al.. Clin Infect Dis 2012:54:167-74 S≤16; I =32-64; R≥128 Piperacillin –tazobactam resistance amongst Enterobacteriaceae in South Africa Blood culture isolates (n=161) of Enterobacteriaceae Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital Lowman South Afr J Epidemiol Infect 2013;28:16-21 S≤16; I =32-64; R≥128 Brink et al. South African Med J 2008;98:586-592 Introduction Combination vs monotherapy for MDR GNB? Combination vs monotherapy for Introduction Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia Combination therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa ? • Pseudomonas remains one of the ultimate Gram-negative pathogens due to the rapidity with which patients succumb to severe pseudomonal infections, as up to 50% of patients with PA bacteremia die within the first 24–72 hours; therefore, prompt administration of effective treatment seems essential. • Empirical combination therapy is recommended for patients with known or suspected P.aeruginosa infection (Surviving Sepsis guidelines) as a means to: – decrease the likelihood of administering inadequate antimicrobial treatment – to prevent the emergence of resistance – to achieve a possible additive or even synergistic effect Combination therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa ? • Meta analysis published in 2004 to determine if combination antibiotics reduced survival in Gram-negative bacteremia • No benefit shown, BUT: • Analysis restricted to P aeruginosa bacteremia, OR for combination therapy 0.5 (0.32-0.79, P=0.007), and a 50% relative reduction in mortality with use of combination therapy Safdar N, et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2004;4:519-27 Combination therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa ? • In meta-analysis, Safdar et al included aminoglycoside monotherapy as adequate1 • Single aminoglycoside therapy associated with increased mortality in P aeruginosa bacteremia compared to other antibiotics • Benefit of combination therapy was no longer significant if odds ratio for mortality was recalculated after exclusion of this therapy2 Safdar et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2004;4:519-27 Paul et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5:192-3 2013: Combination therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa? • First large prospective study of P aeruginosa specifically addressing issue of combination versus monotherapy • 593 patients in 10 public hospitals with a single episode of PA bloodstream infection included. 30-day mortality was 30% • Treatment with combination antibiotic therapy did not reduce mortality compared with single antibiotic - 69.4% survival adequate empiric combination Rx (95% CI 59.1–81.6) - 73.5% survival adequate empiric single-drug therapy (95% CI 68.4-79%) Pena et al. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:208-16 2013: Combination therapy for P. aeruginosa? All cause mortality empirical combo vs mono Rx Paul et al. Editorial comment Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:217 -220 2013: Combination therapy for P.aeruginosa? All cause mortality directed combo vs mono Rx Paul et al. Editorial comment Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:217 -220 Combination antibiotic therapy for septic shock? Does this apply to severe pseudomonal sepsis and septic shock? Kumar et al. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1651-64 Combination antibiotic therapy for septic shock? • Survival benefit with combination Rx in this setting has been confirmed by 2 other studies • “Administering a combination of antimicrobials with different mechanisms of action is associated with decreased mortality” • “For patients in septic shock who have a high baseline risk of mortality, combination empiric antibiotic therapy for several days with 2 drugs of different mechanisms of action and with likely activity for the putative pathogen is appropriate. Monotherapy is recommended for patients who are not critically ill and at high risk of death”. Diaz-Martin Crit Care 2012;16:R223 Abad et al. Crit Care Clin 2011:27:e1-27 Caveats: Combination therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa? • The main caveats are: – We do not have data on specific antibiotic combinations on which the rationale of synergism lies – The CIs of adjusted analyses are broad – The benefit of the increased spectrum of coverage in the empirical phase of treatment has not been assessed. – RCTs have not addressed this study population i.e P aeruginosa Paul et al. Editorial comment Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:217 -220 Adding rifampicin to colistin for the Introduction treatment of serious XDR Acinetobacter baumannii infections • This multicenter, parallel, randomized, open-label clinical trial enrolled 210 patients with life-threatening infections due to XDR A. baumannii from ICUs of 5 tertiary care hospitals. • Death within 30 days from randomization occurred in 90 (43%) subjects, without difference between treatment arms (P = .95). This was confirmed by multivariable analysis (odds ratio, 0.88 [95% confidence interval, .46–1.69], P = .71). • A significant increase of microbiologic eradication rate was observed in the colistin plus rifampicin arm (P = .034). • No difference was observed for infection-related death and length of hospitalization. Durante-Mangone et al. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:349-58 Introduction Continuous infusion or extended infusion of β-lactams vs intermittent infusion Continuous infusion (CI) or extended Infusion (EI) vs intermittent infusion (II) • Previously, meta-analysis could not demonstrate benefit of alternative infusion strategies • Three recent studies have contributed to our understanding of alternative β-lactam administrations, and the clinical benefit of such practices • 1st, Falagas et al, in a systematic review and meta-analysis (nonrandomized observational studies) found mortality to be significantly lower among patients receiving extended or continuous infusion of carbapenems or piperacillin-tazobactam compared with those receiving short-term infusions (relative risk, 0.59; 95% confidence interval,0.41–0.83), and this difference in mortality was most pronounced in patients with pneumonia (relative risk, 0.50; 95% confidence interval, 0.26–0.96). Falagas et al. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:272-282 Continuous infusion (CI) or extended Infusion (EI) vs intermittent infusion (II) Falagas et al. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:272-282 Continuous infusion (CI) or extended Infusion (EI) vs intermittent infusion (II) • 2nd study: Dulhunty et al conducted a small-scale, prospective, doubledummy, randomized controlled trial of CI vs II bolus dosing of piperacillintazobactam, meropenem, and ticarcillin-clavulanate in 5 ICUs across Australia and Hong Kong. • Plasma antibiotic concentrations exceeded the MIC in 82% of patients (18 of 22) in the continuous arm, versus 29% (6 of 21) in the intermittent arm (P = .001). • Clinical cure was higher in the continuous group (70% vs 43%; P = .037), but ICU-free days (19.5 vs 17 days; P = .14) did not significantly differ between groups. • Survival to hospital discharge was 90% in the continuous group versus 80% in the intermittent group (P = .47). Dulhunty et al. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:236-44 Reduction of mortality in patients with P. aeruginosa infections treated with extended-infusion cefepime • 3rd recent study: Severe P.aeruginosa infections (bacteremia and/or pneumonia ) treated with cefepime: – 30-min infusion of 2 g every 8 hr (n=390) – 4-h infusion of 2 g every 8 hr (n=202) • Overall mortality significantly lower in the group receiving extended infusion (20% vs 3%; P=0.03) • LOS 3.5 days less for patients who received extended infusion (P=0.36). For patients admitted to the ICU, LOS significantly less in the extended-infusion group (18.5 days vs 8 days; P=0.04) • Hospital costs $23,183 less per patient favoring extended infusion (P=0.13) • Not only clinical, but economic benefits of extended infusions in the treatment of invasive P. aeruginosa infections. Bauer et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013;57:2907-12. Introduction Conclusions Conclusions • Serious ESBL infections • Clinical response rate and mortality (incl. very ill patients) is similar for ertapenem vs mero/imi as empiric treatment option for for bacteraemic ESBL-infections whilst cefepime, even if in vitro sensitive, should not be used for directed Rx of bacteraemic ESBL infections except if MIC ≤ 1mg/L • However, 2 studies have suggested that de-escalation from carbapenems to amox-clav and pip-taz, is safe once in vitrosensitivity has been confirmed and might be a valuable carbapenem-conserving strategy within an ASP Conclusions • Antibiotic combination treatment for GNB • In most instances the evidence for (or against) combination antibiotic therapy is at best circumstantial • Targeted therapy should be instituted once cultures are available in most cases • Question should rather be: under what circumstances is combination therapy beneficial? • Very few RCTs giving clear guidance on the issue – Emerging evidence for serious CPE infections suggest improved survival with combination therapy particularly if combined with a carbapenem Conclusions • Antibiotic combination treatment for GNB (cont) – In contrast, combination therapy for P.aeruginosa appears to offer no benefit but this has to be confirmed in severe sepsis and septic shock – Attempts have been made to improve colistin efficacy for XDR Acinetobacter infections by unorthodox antimicrobial combinations, but none of these proved superiority over colistin monotherapy certainly not in the case of rifampicin • CI or EI or PI vs conventional bolus infusions – Positive data from the observational studies (meta-analysis) and a (small) comparative, double-blinded study suggest that prolonged or continuous infusion of β-lactams is unlikely to be advantageous for all hospitalized patient populations, but may be beneficial for specific groups, such as critically ill patients with higher MIC pathogens, and appears to offer financial benefit TreatingIntroduction serious carbapanemaseproducing Enterobacteriaceae 2 NB considerations -Do u Rx in combination? (CPE) with a combination that -And does combination with a carbapenem make a should include a carbapenem difference? Role of carbapenems in combination for treatment of CPE Outcome of 294 infections caused by carbapenemase producing K pneumoniae according to treatment regimen Tzouvelekis LS, et al. Clin Micro Reviews 2012;25:682-707 Role of carbapenems in combination for treatment of CPE This has been supported by several other studies: Essentially never use colistin or carbapenems alone Combination therapy with 2 (or 3 drugs) that includes a carbapenem (ertapenem or imipenem or meropenem or doripenem) significantly reduces mortality Even if carbapenem is resistant (MIC ≥ 1mg/L) Unfortunately the focus has been on KPC and what do you if carbapenem MICs > 32 µg/ml? In essence, new antibiotics are greatly needed, as is additional prospective research. Zarkatou et al. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2011;17:1798-1803 Falagas et al. Future Microbiol 2011;6:653-666 Lee et al. Annals Clin Microb Antimicrob 2012;11:32 Zubair et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:2108-2113 Tumbarello et al. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:943-950 Quirasi et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012: 56:2108-2113 Overtreatment of CPE infections A study cohort of 42 cases: The mean age of the cohort was 67.7 ± 13.7 y Mean APACHE II score was 17.9 ± 8.6 77% of patients were in ICU K.pneumoniae (84%) was the predominant organism; urine (36%), tissue/wound/drainage (25%), and blood (20%) were the most common sites of collection. All cause mortality was 29% Though 43% of cases were classified as colonization, 56% of these cases were treated with antibiotics. Only 1 patient characterized as colonized subsequently developed infection, 29 days later Nearly half of cases represented colonization, yet the majority were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Determining infection versus colonization is a critical first step in managing patients with CPE. The risk of not treating apparent colonization appears low. Rihani et al. Scan J Infect Dis 2012 ;44:325-9 CRE score: Bedside score to rule out infection with CRE among hospitalized patients Crude and adjusted associations for candidate and final score variables: N=182 pts (ESBL 166, CRE 16) Resident in long-term care facility Renal disease Neurologic disease Reduced consciousness at time of illness Dependent functional status at admission Diabetes mellitus ICU admission Antibiotic exposure in 3 months prior to admission A score of 32 to define “high CRE risk” had Sensitivity of 81% (95% CI: 76%-87%) Specificity of 70% (95% CI: 63%-77%) Positive predictive value of 21% (95% CI: 15%-27%) Negative predictive value of 97% (95% CI: 95%-99.8%). Martin et al. Am J Infect Contr 2013;41:180-182

© Copyright 2026