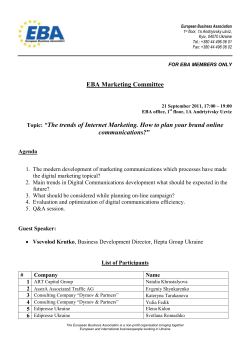

12 22 36