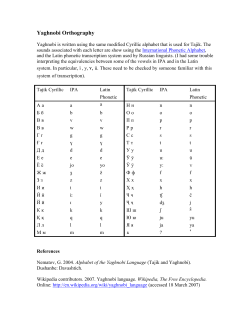

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS The Sino-Alphabet: The Assimilation of Roman Letters