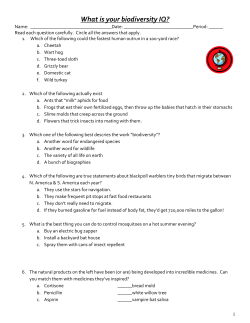

Document 252985