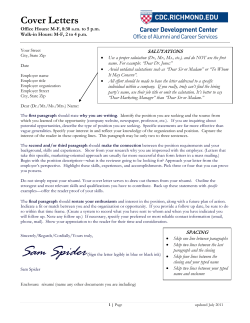

U.S. Department of Justice U.S. Department of Education Notice of Language Assistance