Style Manual A G

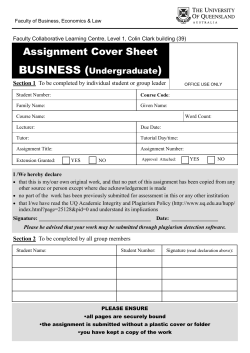

StyleManual A GUIDE TO RESEARCH AND WRITING Edited by David S. Casas 2012 The Luther Rice University & Seminary Style Manual A Guide to Research and Writing First Edition Edited by David S. Casas LUTHER RICE UNIVERSITY & SEMINARY Lithonia, Georgia 29 Copyright © 2012 The Office of Academic Affairs And the Smith Library Luther Rice University & Seminary All Rights Reserved 2 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS..............................................................................................................................3 PREFACE ......................................................................................................................................................4 I. SIMPLE GUIDE TO THE RESEARCH PAPER ..................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................................................. 5 THE COVER SHEET ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 THE TITLE PAGE ........................................................................................................................................................... 7 THE OUTLINE ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 THE INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 THE BODY ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 From page 2 of the sample paper ...................................................................................................................... 10 From page 3 of the sample paper ...................................................................................................................... 12 From page 4 of the sample paper ...................................................................................................................... 12 From page 5 of the sample paper ...................................................................................................................... 13 THE CONCLUSION ...................................................................................................................................................... 13 THE SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................... 14 SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION ............................................................................................................................... 15 Headings & Subheadings ....................................................................................................................................... 15 Bible Book Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... 16 FINAL REMARKS......................................................................................................................................................... 16 II. GUIDELINES FOR AVOIDING PLAGIARISM .............................................................................. 17 III. TIPS FOR EVALUATING RESOURCES ........................................................................................ 24 IV. WRITING AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY .......................................................................... 27 APPENDIX A: A COMPLETE PAPER IN TURABIAN....................................................................... 30 3 PREFACE The Luther Rice University & Seminary Manual of Style has been designed as a supplement to Kate L. Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations: Chicago Style for Students and Researchers, 7th ed., rev. Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, and University of Chicago Press Editorial Staff (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), for use at LRU. Turabian should be consulted for matters not addressed in this manual. There are some LRU faculty members that have contributed in one way or another to the production of this manual. In particular, Dr. James M. Kinnebrew, Dean of the Faculty and Professor of Theology, and his wife, Mrs. Sandra Kinnebrew, deserve special mention for producing the university’s first research and writing guide, Your Simple Guide to the Sample Research Paper: An LRS Primer to Writing Turabian Style (2003), of which forms the majority of the first edition of the LRU Style Manual. At one time or another, Smith Library staff have contributed to sections 2 – 4. Originally separate published documents, these guides have helped students over the last decade avoid the pitfalls of plagiarism and citation mistakes. We thought it appropriate to incorporate this valuable information in this first edition. The contributor to the sample research paper contained herein, often referred to as “that hell paper” (further description of this contribution is contained in Dr. Kinnebrew’s introduction) is former LRU student Marvin M.P. Mullins, who graciously gave permission for its use. As a student at Luther Rice, I often found myself referring to Dr. Kinnebrew’s document and the other helps in order to properly write my papers. Writing in the Turabian format often required much prayer and fasting! It is my hope that this style manual will provide you, the student, with the necessary information to better your writing and conform to the guidelines set forth at LRU. David S. Casas Editor 4 I. SIMPLE GUIDE TO THE RESEARCH PAPER By James M. Kinnebrew, Ph.D. Introduction The Style Manual is offered as a companion document to be used with the paper “Hell: The Necessity and Nature of Divine Retribution” (Appendix A). A student of Luther Rice University & Seminary wrote the latter paper some years ago as a class assignment. With that student’s permission, the paper was slightly revised and has been used for several years to help other students see how to format a research paper according to the guidelines published in Kate L. Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations: Chicago Style for Students and Researchers, 7th ed., rev. Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, and University of Chicago Press Editorial Staff (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007). Mrs. Sandra Kinnebrew has always had a heart for struggling ministerial students, and there is probably no task that causes as much consternation for a new student as that of mastering the rules of academic writing. Seeing this, Mrs. Kinnebrew conducted a two-hour tutorial on the LRU campus to teach local students how to write a Turabian-style paper. As the tutorial students looked at what has come to be known simply as “that hell paper,” Sandy explained point-by-point the various form and style issues reflected there. Students that participated in the tutorial have always been very vocal in their enthusiastic appreciation of the instruction afforded them. Many, even on the doctoral level, have testified that it was the most important two hours of their student career! The present document, now an essential part of RW 500 Intro to Theological Research and Writing, follows the broad outlines of Mrs. Kinnebrew’s instruction and is offered to a new generation of LRU students. With “that hell paper” in one hand (available in Appendix A of this manual) and the PC mouse in the other, the student will walk through the sample paper noticing important aspects of seven different items as they are pointed out in this Style Manual. It would be a good idea to take notes right on the “hell paper.” The instructional tour begins on the first page with the course cover sheet and ends with the final page, the Selected Bibliography. Though it’s not a difficult trip, there is a good bit of ground to cover; so let’s take a walk! 5 The Cover Sheet The first page on the sample paper is called the “Course Cover Sheet.” It should be the first thing the professor sees when he picks up an assignment. On this page are enumerated the following items: 1. The number and name of the course for which the work was done. 2. The nature of the submission—is it a partial submission (are there other assignments that must be done before the final grade is assigned), or is it complete (consisting of the entire course work)? 3. The author(s) and title(s) of the course’s required textbook(s). 4. Submittal information (including the degree being pursued). 5. The student’s name and complete mailing address. 6. The student’s ID number and a daytime phone number (including the area code). 7. The date the work was completed. 8. The student’s academic advisor (this is usually AAO—the Academic Advising Office). 9. The professor who teaches or grades the course. 10. The number of hours (including that very course) that the student has completed toward the degree. 11. The number of hours that remain to be completed before the degree is awarded (not including the present course). Each of these items is important for a proper recording of the submission. Care must be taken not to omit any of them. As for spacing, the information should be centered within the “writing workspace.” This is the area on the page that remains after the margins have been formatted. Margins for the Course Cover Sheet are as follows: 1 ½ inches on the left side. 1 inch on the top. 1 inch on the right side. 1 inch at the bottom. The above margin specifications remain the same on every page except, as will be seen later, pages that begin a major section. Those pages have a 2-inch top margin. Hitting the “underline” key 20 times creates the lines that separate the middle portion of the page from the top and bottom portions. The entire page (as, indeed, the entire paper) is written in Courier New, 12 pt. font, with black ink or Times New Roman, 12 pt., with black ink. Show your creativity in the content, not the fonts or colors. Other than the items noted above (margins, 20 space dividing lines, and font size), no universally standard spacing is possible within the writing workspace. This is because some courses will have a few textbooks, and others will have many; some addresses take three lines to write out, and others take five; etc. 6 The key is to make the spacing uniform and visually pleasing and to keep all of the writing centered in the workspace. The Title Page The second page of the research paper is its title page. Spacing, again, depends on the amount of information (length of title, etc.) that must be included. The key to this page, like the previous one, is threefold. 1. Include every component: a. The title of the paper (all capital letters) b. The professor to whom the work is being sent (using the correct title: Dr., Mr., Mrs., etc., but not degrees: Ph.D., M.A., etc.) c. The course for which the paper was written. d. The student’s name and ID number. 2. Work only within the “writing workspace” 3. Make the spacing between elements as balanced and visually appealing as possible. The Outline A well-conceived outline gives the author a “playing field.” It marks the specific bases that he must touch before he “scores,” and it draws base lines that keep him from running all over creation on his way from one point to the next. It may be the most basic key to a well-written paper. Because of this, one must spend significant thought and time on the outline prior to beginning the paper. Unless the student already possesses a good grasp of the topic, some research will be necessary before an outline can be created. A perusal of encyclopedia articles and introductory textbooks will give one a general knowledge of the paper’s topic and an idea of the issues that merit investigation. With that knowledge in hand, one can decide what points should be covered in the paper, put those points into a logical outline, and use that outline to guide and limit the rest of his research. The third page in the research paper gives the author’s outline, allowing the reader to preview the ground that is about to be covered. Note the following factors: 1. The top margin of this (and any other page that begins a main section of the paper) is 2”. Other margins remain the same (1 ½” on the left, 1” on the right, and 1” on the bottom). 2. This preliminary page is numbered ii (since the title page is considered the first preliminary page of the paper [i], though not numbered, and the course cover sheet is not technically a part of the research paper at all). 3. The page number (here and everywhere) is at the bottom center of the page and must not encroach into the 1” bottom margin. Setting the footer at 1” will ensure that no print violates that margin. 4. The section heading, “OUTLINE,” is in all capital letters, as are the main sections of the outline (anything with a Roman numeral next to it is considered a main section). 7 5. Lesser-level subheadings (those not specified by Roman numerals) are written in upper and lower case letters. In these, the first and last words always begin with capital letters, as do all other words except conjunctions, articles, and prepositions. Note the mnemonic: “Do not CAP conjunctions, articles, or prepositions.” 6. The Roman numerals are arranged so that the dots line up vertically with each other. To do this, one must hit the space bar twice before typing I. and once before typing II. The space bar, then, is not hit at all before typing III., and it is hit once before typing IV. 7. There are two spaces after the dot that follows each numeral or letter in the outline. 8. A paper of this length (8-15 pp.) will usually have a brief and uncomplicated outline, consisting of the INTRODUCTION, the TITLE TOPIC (broken into however many facets of that topic are to be covered), the CONCLUSION, and a SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY. 9. In longer papers, the outline may have more levels of subheadings. If so, the sequence is Roman numeral, capital letter, Arabic numeral, small letter, Arabic numeral in parentheses, and small letter in parentheses. Such intricate dissection is rarely needed and will probably not be used in most classes, but a partial example might be helpful: I. THE PICTURES OF HELL A. Hell As Fire 1. Hell Fire in the Old Testament a. In the Pentateuch 1) Genesis 2) Exodus b. In the Prophets 2. Hell Fire in the New Testament a. In the Teaching of Jesus 1) His proclamation 2) His parables a) The rich man and Lazarus b) The sheep and the goats b. In the Teaching of the Apostles B. Hell As Fury II. THE PUNISHMENT OF HELL NOTE: Every level of heading or subheading must have at least two sections. (In other words, if there is an “I,” there must be an “II”; if there is an “A,” there must be a “B”; if there is a “1,” there must be a “2”; and so forth). 8 HOWEVER, it is not important that every level be divided to the same extent (for example, there are more divisions in the section on Jesus’ teaching than there are on the prophets’ teaching in the above outline). Note, also, that the descending levels are all indented 2 blank spaces beyond the level that precedes them. And, finally, note that the capitalization varies according to levels: The main points are written entirely in capital letters; the subpoints, at levels 1-3, are written in “headline style” (see the first “bullet” on p. 6 above); and levels 4-5 are capitalized “sentence style” (only the first word and proper nouns begin with capital letters). The Introduction Although it appears first, the Introduction is the last part of the paper to be written. This is so for the simple reason that one cannot introduce to someone a thing that does not yet exist (I would like to introduce my grandson to you, but he has yet to be conceived)! Only after the body of the paper is written is the author able to give a concise and accurate Introduction. A striking question, an interesting illustration, a startling statistic, or some other way of engaging the reader’s attention will serve as a good start to the Introduction. The point, however, is not to entertain or even to inform; that is the job of the main body of the paper. The Introduction is simply to engage the reader and let him know what the body of the paper is going to discuss. It is a tried and true method: “Tell them what you are going to tell them; tell them; then tell them what you told them.” The first of those three “tellings” is the job of the Introduction. Notice in the sample paper that the author spends no time in the Introduction arguing for the existence of Hell or telling what its nature is. In the Introduction, he simply says that those two topics are about to be discussed. As for format, note the following: 1. Because this begins a major section of the paper (i.e., it rates a Roman numeral in the outline), the top margin is 2”. Other margins remain the same. 2. The section heading, “INTRODUCTION,” is in all capital letters. 3. This is the first page of the paper proper, so it is numbered “1.” (Without the quotation marks and the period of course!) 4. Every section of the paper, i.e., every item that merits mention in the outline, should have at least two paragraphs, as seen in the sample paper’s Introduction. The Body The body of the paper contains the results of the author’s research on his topic. This is the “tell them” part of the paper. Note the following format and writing style factors: 9 From page 2 of the sample paper 1. Since this begins a major section of the paper, it starts on a fresh page (even though the Introduction did not use all of page 1). 2. Since it begins a major section, the top margin is 2” deep. Other margins remain the same. 3. The major heading is the same as the title of the paper and is written in all capitals. 4. The first-level subheading (any element marked with a capital letter in the outline) is centered, italicized, and written with both upper and lower case letters. NOTE: The definite article “The” is capitalized because it is the first word in the subheading; “of” is not capitalized, because it is a preposition. (A dictionary will help when one is uncertain what part of speech a particular word is.) 5. All headings and subheadings appear in the text exactly as they appeared in the outline (minus the numerals or letters). In other words, if the outline says “The Necessity of Hell,” the subheading on page 2 cannot say “Why Hell Is Necessary.” 6. There is a triple space (two blank lines) between the main heading (HELL: THE NECESSITY AND NATURE OF DIVINE RETRIBUTION) and the first-level subheading (The Necessity of Hell). Some typists prefer to double space the entire paper and then go back to places where a triple space is needed and insert a manual carriage return to add the extra blank line. 7. There is a double space (one blank line) between the subheading and the following text. 8. Paragraphs are indented 5 spaces (this is the default setting for most word processors). 9. Sentences are separated by 2 spaces. That is, there are two blank spaces after the period (or other end punctuation). 10. When an end quotation mark and a punctuation mark are juxtaposed (as in the next to last sentence of the first paragraph), the order is as follows: a. Periods and commas always precede the quotation mark. b. Semicolons and colons always follow the quotation mark. c. Question marks and exclamation points precede the quotation mark if they are a part of the quoted material, but they follow the quotation mark if they are not. 11. Hitting the underline key 20 times forms the line that separates text from footnotes. If you are using Microsoft Word 2007 or above, the line is automatically added when a citation is inserted. 10 12. To properly format footnotes in MS Word 2007 or above, do the following: a. From the insert menu, choose “footnote”. b. Under location, choose the “beneath the text” option, instead of bottom of page. This option will help avoid the program’s default widow/orphan function applied to footnotes. 13. Footnotes are numbered with a superscript numeral. In the text, that number comes after the quotation mark (see fn. 1). Each footnote is single-spaced, with a double space between the notes. 14. Footnotes are numbered consecutively throughout the paper (in other words, one does not renumber from 1 just because he is on a new page). 15. The preference at LRU is that the word “Bible” and its synonyms (Scripture, Gospel, Canon, Word, etc.) be capitalized, as in the second sentence on p. 2. On the other hand, the related adjectives (biblical, scriptural, canonical, etc.) are not to be capitalized. 16. When the author mentions another person for the first time, the full name should be given (e.g., A. E. Hanson, not Hanson). After the first mention, a person may be referred to by last name alone. Note also that there is a space between initials in a name. 17. Book titles are italicized (not underlined) in Upper and Lower Case letters. 18. Scripture references given after a quote are noted parenthetically in the text, not in footnotes. 19. A Scripture reference that is an integral part of a sentence (as is Matt 25.46 in the last sentence on p. 2) is not put in parentheses. Only things that could be omitted without changing the meaning of the sentence should be put in parentheses. 20. There is no period after the abbreviation of a Bible book, but there is a period (not a colon) between the chapter and verse of a reference. 21. The first time a Scripture is quoted (not cited), the version used should be stated in a footnote (see fn. 2 in the sample paper). 22. Names in footnotes are written in normal order (first name first). 23. Dictionary articles are named in quotation marks after the abbreviation s.v. (sub verbo, Latin, “under the word”). If the article is signed, its author’s name is given in the footnote. Note the order of information. 24. If a source is going to be used repeatedly, the author may wish to designate an abbreviation for that source in the first citation and use the abbreviation thereafter (e.g., DCT in footnote 1, cf., fn. 7). 11 From page 3 of the sample paper 1. When Scripture is quoted, as seen on line 4 of page 3, the order after the quote is: a. End quotation marks b. Parenthetical reference c. Period (or other end punctuation) 2. When a quote is four or more lines of text, it should be “blocked.” A block quote is single-spaced and indented 4 blank spaces on the left. It is not indented on the right at all. It is separated from the rest of the text by a blank line before and after. 3. There are no quotation marks used in a block quote (unless they appear in the original source). The blocking of the text serves the purpose of notifying the reader that someone else is being quoted. 4. Quoted material should be reproduced exactly as it is in the original source (note that the Scripture references in the block quote are not in the style preferred by LRU, but they are rightly reproduced as they appeared in the original). 5. Note the order of footnote data: Author’s name (natural order), book title (in italics), city, publisher, and date (all in parentheses), and page numbers (numbers only, no “p.”). Note, too, the punctuation: Author, COMMA; title BEGIN PARENTHESES; city, COLON; publisher, COMMA; date, END PARENTHESES & COMMA; page number, PERIOD. 6. If the publisher’s city is well known (e.g., Nashville), it is not necessary to note the state. If the city is not so well known (e.g., Valley Forge), the two-letter state abbreviation used by the United States Postal Service is given. From page 4 of the sample paper 1. There is a triple space (two blank lines) between the last line of text and the following subheading (as seen above). 2. There is a double space (one blank line) between the subheading and the following text (like above). 3. The text (other than block quotes) is double-spaced. 4. Foreign language words are italicized (unless they have become a commonly recognized part of the English language, e.g., the French word “eureka”). 5. Once a source has been footnoted, subsequent uses of that source may be noted with an abbreviated reference (author’s last name, title, and page number). 12 From page 5 of the sample paper 1. Reprint editions are footnoted as in fn. 6. The abbreviation “n.d.” signifies that there is “no date” given for the original publication. 2. “Ibid.” signifies that the footnoted quote is from the same source cited in the previous note. “Ibid.” without a page number means “same source, same page.” 3. “Ibid.” should not be used as the first (or only) footnote on a page, since such a use would require the reader to search other pages for the referent note. The Conclusion The Conclusion wraps things up. This is where, having “told” his readers all he wanted to tell them, the writer “tells them what he told them.” New information is not appropriate here. An illustration, application, or short quote might be relevant, but the purpose of the Conclusion is to reiterate the points that were made in the body of the paper. Note these form and style points in the sample paper (p. 7): 1. This being the first page of another major section of the paper, the top margin is 2” deep. All other margins remain the same. 2. The section heading, “CONCLUSION,” is written in all capital letters. 3. There are two blank lines (triple spacing) between the heading and the following text. 4. In this instance the first line of the block quote is indented 8 blank spaces, because in the original source (the Holman Bible Dictionary) this material began a new paragraph. In such cases, the block quote is indented 4 spaces (to “block” it), and the first word is indented 4 more spaces (to show that, in its original context, it was the beginning of a new paragraph). 5. This entire paper has been written in the third person (no “I,” “you,” “we,” etc.). This is the proper style for an academic paper. When the writer does refer to himself at the end, he uses the phrase “this writer.” This is acceptable, but there is actually no reason for a self-reference here. The sentence would read smoother and convey the same meaning if it were written: “Finally, Hell can be described as a place of demons, distress, deprivation, debts coming due, and duration.” The reader knows whose paper he is reading, so there is no reason to say, “This is what this writer thinks.” Avoiding self-reference is a discipline with which many students struggle, but once mastered it improves their writing immensely. 6. One other point should be made regarding writing in the third person. By that rule, phrases such as “our Lord Jesus Christ,” “in our day and age,” etc. are prohibited. The author of the sample paper avoided that mistake on p. 7, calling the Savior “the Lord Jesus.” 13 The Selected Bibliography The final section of the research paper is the “SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY.” It lists every work that is mentioned in the paper, whether actually quoted or not. It may also contain other works that the writer found helpful in researching the topic, even though those works were not quoted, or even mentioned in the paper. Titles that were never consulted should not be included in this list. 1. The top margin is 2” because this is the beginning of a new section of the paper. 2. The correct heading is “SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY,” not simply “BIBLIOGRAPHY.” 3. There is a triple space (2 blank lines) between the heading and the first entry. 4. The entries are single-spaced with a double space (1 blank line) between each entry. 5. The entries contain all of the information that the footnotes contained (except page numbers), but the arrangement and punctuation are different. 6. The first line of each bibliographical entry is flush with the left margin, but all subsequent lines are indented 5 empty spaces. 7. Entries are arranged alphabetically by the author’s last name or, if no author is given, the title. Note: if the title begins with an article, as The Holy Bible, it is alphabetized by the second word in the title. 8. The general arrangement of an entry is as follows: The author’s last name, a COMMA, the first name and (if applicable) middle name or initial, a PERIOD, the book title (in italics), another PERIOD, the city, a COLON, the publisher, a COMMA, the date, and a final PERIOD. 9. Dictionary and encyclopedia articles vary slightly from the above (see the sample). 10. Journal and periodical articles have another arrangement, as do works with more than one author (see the samples). 11. In bibliographical entries, and only there, a period is followed by only one blank space. 12. In longer Bibliographies, it is helpful to separate the various kinds of resources (books, periodicals, lexicons, encyclopedias, etc.) with centered, italicized subheadings. 14 Supplemental Information The preceding “walking tour” has stopped at all the major points of interest in the sample research paper. It has likely pointed out more than most students ever knew was there. Still, there are a few important details that could not be seen from the vantage points visited in this brief “walk through.” The sample paper, for example, only had two levels of heading/subheading. What is the proper placement for headings beyond those two levels? The sample paper cited enough Scripture to clue one in to the fact that the preferred method of abbreviation might not be the method that the student has been accustomed to using, but it did not give the accepted abbreviations for all the Bible books. These considerations and others follow. Headings & Subheadings Turabian’s Manual gives the following instructions for the placement of different subheadings (A.2.2): 1. Main Headings (those items denoted by a Roman numeral in the outline) are written in all capital letters and centered at the top of a new page (with a 2” top margin): HELL: THE NECESSITY AND NATURE OF DIVINE RETRIBUTION 2. First Level Subheadings (capital letters in the outline) are centered, italicized, and written in headline style (upper & lower case letters) with a triple space (two blank lines) after the preceding text: The Necessity of Hell 3. Second Level Subheadings (Arabic numbers in the outline) are centered, written in normal text (not italics), and capitalized in headline style: The Doctrine of Hell in the New Testament 4. Third Level Subheadings (small letters in the outline) are flush to the left margin, italicized, and capitalized in headline style: Hell in the Teaching of Jesus 5. Fourth Level Subheadings (parenthetical numbers in the outline) are flush to the left margin, written in normal text, and capitalized sentence style: Hell and Jesus’ parables 6. Fifth Level Subheadings (parenthetical letters in the outline) are written as “run-in” headings at the beginning of a paragraph. They are italicized and capitalized in sentence style with a period at the end: 15 The rich man and the beggar. When Jesus told the story of the rich man and Lazarus, the concept of a place of eternal torment was widely accepted among the rank and file of Israel. What His audience found surprising was not that there was a Hell, but that the rich might go there. Bible Book Abbreviations OT: Gen Exod Lev Num Deut Josh Judg Ruth 1-2 Sam 1-2 Kgs 1-2 Chr Ezra Neh Esth Job Ps (Pss-plural) Prov Eccl (or Qoh) Cant Isa Jer Lam Ezek Dan Hos Joel Amos Obad Jonah Mic Nah Hab Zeph Hag Zech Mal NT: Matt Mark Luke John Acts Rom 1-2 Cor Gal Eph Phil Col 1-2 Thes 1-2 Tim Tit Phlm Heb Jas 1-2 Pet 1-2-3 John Jude Rev Apocrypha: Add Esth Bar Bel 1-2 Esdr 4 Ezra Jdt EpHer 1-2-3-4 Mac PrAzar PrMan Sir Sus Tob Wis Final Remarks You may have noticed that the sample paper bears traces of a sermonic style. While alliteration, illustration, and other elements common to the pulpit may be acceptable if used with restraint, such elements are certainly not required; and they must never be allowed to get in the way of objective, clear, and scholarly expression. The preceding pages have covered most of the things you need to know for writing papers at LRU. Inevitably, though, questions will arise that were not addressed in this brief survey. The two sources that will prove to be most helpful in such cases are: Kate L. Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations: Chicago Style for Students and Researchers, 7th ed., rev. Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, and University of Chicago Press Editorial Staff (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007) Vyhmeister, Nancy Jean. Quality Research Papers. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001. 16 II. Guidelines for Avoiding Plagiarism By Chris Morrison (Originally published 2008) Purpose: The purpose of these guidelines is to help you understand what plagiarism is and how to avoid it intentionally or unintentionally. What is Plagiarism? Plagiarism: According to the American Heritage Dictionary, 2nd College Edition, plagiarism is defined as taking and using "as one's own the writings or ideas of another." Plagiarism shall include failure to use quotation marks or other conventional markings around material quoted from another source. Plagiarism shall also include paraphrasing a specific passage from a source without indicating accurately what that source is. Plagiarism shall further include letting another person compose or rewrite a student's written assignment. Thus, plagiarism is any instance in which a person uses another’s ideas or words, but does not provide the source of the information in his or her paper through proper documentation (i.e., footnotes). As examples will show, bibliographic entries, while necessary, are not sufficient. Footnotes or endnotes must be provided to credit specific portions of a paper to their original sources. Seminary policies on plagiarism Luther Rice University & Seminary considers plagiarism a completely unacceptable practice. The quotation above is from the LRU catalog; penalties for plagiarism are stated as follows: Any student proven to have committed [plagiarism] will receive an “F” for the course and will receive an academic warning. If the student is proven to have been guilty a second time, he or she will be dismissed. Given these penalties, our advice concerning plagiarism is very simple: don’t do it. Here, we will briefly walk through several steps you can take to ensure that you don’t violate these rules. 1. Document everything! Most people know that you have to reference quotes, but you must go further. If you get an idea from another person, you must provide documentation. This includes paraphrases of someone else’s work as well as short, three to four word phrases that come directly from another source. 17 Example 1: Word-for-Word Plagiarism Original Citation It is important to understand the distinction between bibliology and apologetics. The Scriptures can be demonstrated to be trustworthy and reliable by objective facts from various fields of study. This is the purpose of the studies called apologetics or Christian evidences. By contrast, bibliology begins where apologetics ends. The student begins with the conclusion that the Bible is trustworthy. He then proceeds to research the Scriptural teachings about the origin and nature of Scripture.1 Excerpt from a Sample Paper There has often been confusion on the difference in bibliology and apologetics. Steven Waterhouse clarifies the issue, saying: It is important to understand the distinction between bibliology and apologetics. The Scriptures can be demonstrated to be trustworthy and reliable by objective facts from various fields of study. This is the purpose of the studies called apologetics or Christian evidences. By contrast, bibliology begins where apologetics ends. The student begins with the conclusion that the Bible is trustworthy. He then proceeds to research the Scriptural teachings about the origin and nature of Scripture. This is a clear instance of plagiarism. The author took Waterhouse’s words and used them without providing the appropriate documentation. This is true even though he alerted the reader that these were the words of another. You must provide a footnote demonstrating your source. Example 2: No quotation marks around direction quotation and no footnotes Original Citation Excerpt from a Sample Paper It is important to understand the distinction There has often been confusion on the between bibliology and apologetics. The difference in bibliology and apologetics. In Scriptures can be demonstrated to be the field of apologetics, Scriptures can be trustworthy and reliable by objective facts demonstrated to be trustworthy and reliable from various fields of study. This is the by objective facts from various fields of purpose of the studies called apologetics or study. By contrast, bibliology begins where Christian evidences. By contrast, bibliology apologetics ends. The student begins with begins where apologetics ends. The student the conclusion that the Bible is trustworthy. begins with the conclusion that the Bible is He then proceeds to research the Scriptural trustworthy. He then proceeds to research teachings about the origin and nature of the Scriptural teachings about the origin and Scripture. nature of Scripture.2 This is also a clear example of plagiarism. Notice that the author used, again, Waterhouse’s words without giving him due credit. Additionally, the author did not even alert the reader that the words were, in fact, from another source. 1 Steven W. Waterhouse, Not by Bread Alone: An Outlined Guide to Bible Doctrine, rev. ed. (Amarillo, TX: Westcliff Press, 2003), 2. 2 Ibid. 18 Example 3: Paraphrase without citation Original Citation It is important to understand the distinction between bibliology and apologetics. The Scriptures can be demonstrated to be trustworthy and reliable by objective facts from various fields of study. This is the purpose of the studies called apologetics or Christian evidences. By contrast, bibliology begins where apologetics ends. The student begins with the conclusion that the Bible is trustworthy. He then proceeds to research the Scriptural teachings about the origin and nature of Scripture.3 Excerpt from a Sample Paper There has often been confusion on the difference in apologetics and bibliology. In the former, the trustworthiness of Scripture is proven by observing and examining the facts that concern it. The latter, however, is not concerned with proving the Scriptures are true. Rather, Bible student assumes the trustworthiness of Scripture and seeks to understand what it says about its own nature and origin. This is still another example of plagiarism. Even though the author did not use Waterhouse’s words directly, the idea clearly came from his work. When the author took Waterhouse’s ideas without giving him proper credit, he committed literary theft (plagiarism). Example 4: Proper citation style Original Citation It is important to understand the distinction between bibliology and apologetics. The Scriptures can be demonstrated to be trustworthy and reliable by objective facts from various fields of study. This is the purpose of the studies called apologetics or Christian evidences. By contrast, bibliology begins where apologetics ends. The student begins with the conclusion that the Bible is trustworthy. He then proceeds to research the Scriptural teachings about the origin and nature of Scripture.4 Excerpt from a Sample Paper There has often been confusion on the difference in apologetics and bibliology. The purpose of apologetics is to show that “the Scriptures can be demonstrated to be trustworthy and reliable by objective facts from various fields of study.”1 Bibliology, though, assumes the trustworthiness of the Scriptures and “proceeds to research the Scriptural teachings about the origin and nature of Scripture.”2 ________ 1 Steven W. Waterhouse, Not by Bread Alone: An Outlined Guide to Bible Doctrine, rev. ed. (Amarillo, TX: Westcliff Press, 2003), 2. 2 Ibid. This is not plagiarism. In both instances in which the writer used Waterhouse’s words, he provided both quotations and a footnote to 1) differentiate his words from the original source, and 2) to provide documentation so that the reader may find the original statement. 3 4 Ibid. Ibid. 19 Example 5: Proper citation style Original Citation It is important to understand the distinction between bibliology and apologetics. The Scriptures can be demonstrated to be trustworthy and reliable by objective facts from various fields of study. This is the purpose of the studies called apologetics or Christian evidences. By contrast, bibliology begins where apologetics ends. The student begins with the conclusion that the Bible is trustworthy. He then proceeds to research the Scriptural teachings about the origin and nature of Scripture.5 Excerpt from a Sample Paper There has often been confusion on the difference in apologetics and bibliology. In the former, the trustworthiness of Scripture is proven by observing and examining the facts that concern it. The latter, however, is not concerned with proving the Scriptures are true. Rather, Bible student assumes the trustworthiness of Scripture and seeks to understand what it says about its own nature and origin.1 ________ 1 Steven W. Waterhouse, Not by Bread Alone: An Outlined Guide to Bible Doctrine, rev. ed. (Amarillo, TX: Westcliff Press, 2003), 2. This is also an appropriate citation and, thus, not plagiarism. The author paraphrased Waterhouse’s words and therefore no quotation marks were necessary, but he also provided a footnote pointing to the original source. 2. Be careful to immediately document quotations. Direct quotations, be they in-paragraph or block, must be footnoted immediately. This is in contrast to paraphrases or the taking of general ideas, which may be footnoted at the end of the paragraph in which they are found. Consider the following examples: Example 1: Improperly cited direct quotation Original Citation Excerpt from a Sample Paper Of all typical things in the Old Testament, While there are many examples of typology undoubtedly the tabernacle was the most in the Old Testament, “undoubtedly the complete typical presentation of spiritual tabernacle was the most complete typical truth. It was expressly designed by God to presentation of spiritual truth.” It is so provide not only a temporary place of extensive, in fact, that this paper will only worship for the children of Israel in their take time to study its sacrificial aspects and wanderings but also to prefigure the person their relationship to Jesus Christ.1 and work of Christ to an extent not provided __________ 1 by any other thing.6 John F. Walvoord, Jesus Christ our Lord (Chicago: Moody Press, 1969), 73. Even though there are quotation marks and a footnote, this would still fall under the category of plagiarism. The footnote at the end implies that the material itself comes from 5 6 Ibid. John F. Walvoord, Jesus Christ Our Lord (Chicago: Moody Press, 1969), 73. 20 Walvoord’s work, but leaves the quote’s origin unspecified. To correct the mistake, the student should place the footnote immediately after the closed quotation Example 2: Proper citation style Original Citation Of all typical things in the Old Testament, undoubtedly the tabernacle was the most complete typical presentation of spiritual truth. It was expressly designed by God to provide not only a temporary place of worship for the children of Israel in their wanderings but also to prefigure the person and work of Christ to an extent not provided by any other thing.7 Excerpt from a Sample Paper While there are many examples of typology in the Old Testament, the tabernacle provides us with the most complete prefiguring of Christ. Its original purpose was to be a portable temple, of sorts, but God so designed it that, upon reflection, Jesus’ person and work could clearly be seen. Because the typology is so extensive, this paper will focus on just one of the tabernacle’s aspects and it’s relationship to Christ, namely, its sacrificial system.1 __________ 1 John F. Walvoord, Jesus Christ Our Lord (Chicago: Moody Press, 1969), 73. This example is acceptable. No direct quotation was used, and the information taken from Walvoord within the paragraph was documented in a footnote at the end. Occasionally, you may even use a footnote in the middle of a sentence, as in the example below: Example 3: Footnote in the middle of a sentence Original Citation Excerpt from a Sample Paper Of all typical things in the Old Testament, Even though the tabernacle provides us with undoubtedly the tabernacle was the most the most complete prefiguring of Christ complete typical presentation of spiritual anywhere in the Old Testament1, we must be truth. It was expressly designed by God to careful not to lose sight of its original provide not only a temporary place of purpose and place an undue emphasis on its worship for the children of Israel in their typological role, thus distorting our wanderings but also to prefigure the person exegesis. and work of Christ to an extent not provided __________ 1 by any other thing.8 John F. Walvoord, Jesus Christ Our Lord (Chicago: Moody Press, 1969), 73. 3. Document every idea taken from another source, but don’t footnote common knowledge. Many things in our world are considered “common knowledge,” and therefore do not have to be documented. Examples of this would include that George Washington was the first president of the United States, that English sentences begin with capital letters, and that Jesus was a Jewish man. If you are unsure whether or not your statement is common 7 8 Ibid. Ibid. 21 knowledge, ask yourself where you got the information. Was it something you picked up in grade school? If so, it is probably common knowledge. Is it something you learned as you were researching your topic? If so, then it almost certainly needs to be documented. Or you could ask yourself whether or not a typical reader would already be aware of the fact you are presenting, or would he or she want to see where you got your information. The former case would be one of common knowledge; the latter would need to be documented. If ask yourself these questions and still aren’t sure, err on the side of caution: reference the citation (but again, if there is no citation but rather it is something you already knew, then the chances are it is either common knowledge or you are assuming more than you can prove!). Example 1: Proper citation style (Common Knowledge) Original Citation Excerpt from a Sample Paper Like all of Paul’s writings, Romans opens There is little reason to doubt that Romans with a claim of Pauline authorship. No was written by Paul. First, we immediately critics have presented satisfactory reasons notice that it begins with a claim to Pauline for rejecting this claim . . . . The letter’s authorship. obvious Pauline traits make it one of the Hauptbriefe, and support for an author other than Paul has little acceptance among New Testament scholars.9 This is not plagiarism. The fact that Paul wrote Romans, as well as the fact that the book opens with the claim that Paul is the author, is common knowledge. Just because Lea said the same thing does not mean we must credit him with the idea. Example 2: Citing common knowledge, but using someone else’s words Original Citation Excerpt from a Sample Paper Like all of Paul’s writings, Romans opens Like all of Paul’s writings, Romans opens with a claim of Pauline authorship. No with a claim of Pauline authorship. But can critics have presented satisfactory reasons this claim be justified? This paper will begin for rejecting this claim . . . . The letter’s by examining the letter’s obvious Pauline obvious Pauline traits make it one of the traits. Hauptbriefe, and support for an author other than Paul has little acceptance among New Testament scholars.10 This student, on the other hand, has committed plagiary. While the facts are common knowledge, he has used Lea’s words, verbatim, without giving him due credit. Remember, plagiarism is taking someone else’s words or ideas and not giving him proper credit. 9 Thomas D. Lea and David Alan Black, The New Testament: Its Background and Message, 2d ed. (Nashville, TN: Bradman & Holman Publishers, 2003), 391. 10 Ibid. 22 Suggestions for avoiding plagiarism Having the right approach to research will help you avoid plagiarism in general. Here are two good rules of thumb. First, if you are writing a research paper, expect the main body of your work to contain at least one footnote in every paragraph (excluding, possibly, concluding of summarizing paragraphs). If you have one a paragraph that doesn’t have any references, then it is likely either unnecessary, or you are in danger of plagiarism. This is because the body of your research paper is building your argument, and to do that, you have to present data. But because you get your data from your research, you will have to document the data you are providing. If, then, you have a paragraph that is not introductory or a summary, and you provide no footnotes, then you’ve either not provided any data in that section (in which case, you should ask yourself if you need it at all), or you’ve given data that you have not documented. Second, a research paper is not a long series of quotes, and research in general is more than looking for quotes to use. If all you are doing is stringing quotes together, you are more apt to fall into plagiarism. Instead, when you research, you should be looking at answering a specific question within your topic at any point in time. If a source helps you answer that question, then include and footnote it in your paper. Use a direct quotation if the statement is particularly memorable or if you want to lend extra authority to your argument. But otherwise, paraphrase the statement or idea, provide the appropriate documentation, and you will be off to a great start. Student Plagiarism Websites http://library.acadiau.ca/tutorials/plagiarism/ http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/589/01/ If you have any further questions, email the library at [email protected] 23 III. Tips for Evaluating Resources By Hal M. Haller 1. Kind of Information Note that each reference work has its own peculiar set of characteristics. You need to know the kind of information that is contained in the various kinds of reference works such as directories, indexes, concordances, dictionaries, handbooks, encyclopedias, bibliographies, commentaries, surveys, outlines, and introductions in order to search intelligently. For instance, dictionaries provide definitions and descriptive information and generally have more brevity than encyclopedias that provide more in-depth treatments of a subject. 2. Scope of Information Along with the kind of information, the student should be aware of the scope of information. Some reference works only treat a specific aspect of a subject whereas others treat a broader aspect. For example, an encyclopedia of ethics would be broader in scope than an encyclopedia in bioethics. In looking up pertinent information on euthanasia, both sources should be consulted. 3. Currency of Information Next, be aware of the currency of information. Chafer’s Systematic Theology addresses issues that were important to the author and his constituency in the late forties and early fifties. Some of the issues Chafer raises are of timeless value; they are still being discussed and debated. However, Chafer will not make you aware of some of the current issues (for instance, how postmodernism and open theism relates to theology today). 4. Currency of Nomenclature Be aware of currency of nomenclature. Language changes. Philosophical and cultural currents force these changes. Under some of the older references works, if you wish to read about homosexuality, you may have to look under the term sodomy in the table of contents, in the topic headings, or in the index. Remember that the term “gay” was not used in the “gay nineties” (1890’s) the same way it is today. Older references may make reference to Negroes, but the currently accepted term is Afro-Americans. In looking at some older works the term abortion is not there, but infanticide is. 5. Viewpoint of the Author(s) Be aware of the viewpoint of the author(s). Some reference works are produced by theological conservatives and others by theological liberals. Sometimes works will contain a blend of the two viewpoints by the same author or by different authors. The dividing line between liberals and conservatives by and large is attitude towards the inerrancy of Scripture and a normal literal method of interpretation. Note whether the author is Baptist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Catholic, Orthodox, Wesleyan, etc. Note 24 whether the author is dispensational or covenant or whether the author is premillennial, amillennial, or postmillennial. If you are reading church history material, note whether the author has a horizontal or vertical way of describing it. For instance, some will describe the ministry of George Whitfield, the great English evangelist, as relating in some way to God’s providence. Others will seek to explain his ministry more in sociological terms without making any judgments on the workings of God in his life, although privately they might hold an opinion. Even in the area of Bible translation viewpoints are sometimes expressed. For instance, one translation that has a feminist bias translates John 3:16 as “God gave His only begotten child” rather than “God gave His only begotten Son,” thus avoiding the masculine gender of Christ. Because a writer tells you that he believes in the inspiration of Scriptures may not in and of itself tell you where he stands on inerrancy. He may believe the Bible is inspired, errors and all! You must dig deeper. 6. Qualifications of the Author(s) Be aware of the qualifications of the author(s). Ask, “Is the author qualified by his academic credentials, experience, and peer recognition to write what he does?” “Does he show evidence of the research necessary to reach the conclusions he does?” “Does the writer communicate clearly or is he sloppy in his thinking or expression?” Do consider that sometimes an author may be eminently qualified by credentials and experience, but not able to reach satisfactory conclusions on particular subjects because of one reason or another. In other words, beware of the brilliant, but unbalanced scholar. Remember that scholars can and sometimes suppress information they do not like because they are members of a fallen race (cf. Rom. 1:18). 7. Reputation of the Publisher Be aware of the reputation of the publisher. Some publishers publish a lot of sensationalistic material with little support. For instance, there is the publisher who published the pamphlet, “88 Reasons Why the Rapture Will Occur in 1988.” As authors have viewpoints, publishers may create a reputation for favoring a certain viewpoint. For instance, reference works published by Moody Press are theologically conservative; reference works published by Abingdon Press are generally much less so. Both the qualifications of the author and the reputation of the publisher have to do with reliability. Are the sources I am using trustworthy? Be aware of the level of audience for which the work is intended. Sometimes the preface or introduction to the reference work will actually tell you that the work is intended for laymen and busy pastors or that it is intended for more serious study. Usually works that are more popular in nature have less in depth research behind them than works of a more detailed scholarly nature. This is not always true. Sometimes popular works are written by someone with a great deal of scholarship behind them, but wear their scholarship lightly. An example would be The Hungry Inherit, a devotional work by Zane C. Hodges, a New Testament scholar. 25 8. The Importance of Introductions, Symbols, and Explanations Besides becoming aware of certain matters, one should become familiar with the introductions, symbols, abbreviations, and explanations that are unique to each reference work. Most of us would rather just dive in and get the information, but we must be careful to understand how the author meant to lay out his material or we may misunderstand the proper use of it. Or, to put it another way, “Before all else fails, read the directions. Recommended Reading Badke, William B. The Survivor’s Guide to Library Research. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1991. Badke, William B. Research Strategies: Finding Your Way Through the Information Fog. New York: IUniverse, Inc, 2004. Bauer, David R. An Annotated Guide to Biblical Resources for Ministry. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2011. Barber, Cyril J., and Robert M. Krauss. An Introduction to Theological Research: A Guide for College and Seminary Students. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2000. Barber, Cyril J. The Minister's Library. Chicago: Moody Press, 1985. Bolner, Myrtle S., and Gayle A. Poirier. The Research Process: Books & Beyond. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co, 2007. Durusau, Patrick. High Places in Cyberspace, 1996. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1996. Glynn, John. Commentary & Reference Survey: A Comprehensive Guide to Biblical and Theological Resources. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Academic & Professional, 2007. Hysell, Shannon. American Reference Books Annual 2012. Libraries Unltd Inc, 2012. Katz, William A. Introduction to Reference Work, Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill, 2001. Kepple, Robert J., and John R. Muether. Reference Works for Theological Research. Lanham: University Press of America, 1992. Rosscup, James E. Commentaries for Biblical Expositors: An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Works. The Woodlands, TX: Kress Christian Publications, 2004. Vyhmeister, Nancy J. Quality Research Papers for Students of Religion and Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008 26 IV. Writing an Annotated Bibliography By LRU Library Staff (collective effort) (Originally published in 2008) Your professor may have different requirements for his annotated bibliography assignment. Please check with him before following the advice in this document. What is a bibliography? A bibliography is a systematically arranged list of resources such as books and journal articles used for research. What is an annotation? An annotation could be an explanation, description, summary, critical evaluation, or a combination of all of them. What is an annotated bibliography? An annotated bibliography is a systematically arranged list of resources such as books and journals used for research with a brief summary and critical evaluation of each resource. A bibliography provides you with the author, title, and publication details of resources used; an annotated bibliography adds a paragraph of summary and evaluation to each resource. What is the purpose of an annotated bibliography? It reflects the depth of your research and understanding of the topic. It reviews the literature published on a topic. How long should it be? The length of each entry depends upon the specific guidelines your professor has given you. An annotation can be as short as one sentence. Generally, each annotation should be one single paragraph and not exceed 150 to 200 words, or three to five sentences. How does one choose resources for an annotated bibliography? Choosing resources for an annotated bibliography involves doing research just like any other project. Choose peer-reviewed journals and scholarly monographs that provide a wide variety of perspectives on your topic. The quality of your bibliography will depend on your selection of sources. Follow the specific guidelines your professor may have given you. 27 What goes into an annotated bibliography? The first part of the annotated bibliography is the bibliography itself. This should be citing the books or articles in alphabetical order in Turabian format. The second part depends on what is being asked by your professor. If your professor is asking for a descriptive annotation (without analyzing the author’s findings or conclusions), simply summarize the scope and content of the resource. If the professor is asking for a critical and evaluative annotation, provide a critical assessment of the resource with the descriptive annotation. A critical or evaluative annotation examines the strengths, weaknesses, and biases of the resource. Follow these steps for a critical assessment of a book or an article. 1. Get an idea about the author’s thesis and conclusion by reading the introduction, table of contents, and conclusion. 2. Evaluate the author’s credentials (educational background, reputation, and knowledge on the topic). How qualified is the author? Does the author have some authority in the field? 3. Evaluate sources cited within the work and see whether they appear to be credible and scholarly without much controversy. Is the author’s work in tune with the established scholarship? 4. Evaluate the publisher’s credentials. Is the publisher reliable and reputable? 5. Evaluate the relevance of the information. Is the source/information contained within the source relatively recent? What does an annotated bibliography in Turabian format look like? Sample citations and annotations: SELECTED ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Davidheiser, Bolton. Evolution and Christian Faith. Philadelphia: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1969. Young-earth creationist critique of evolution. The section on teleology is especially good. There are many helpful appendices as well. This book is so well-written, it should be updated with more recent documentation and reprinted. Geisler, Norman L., and J. Kerby Anderson. Origin Science: A Proposal for the Creation-Evolution Controversy. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1987. Important book arguing for a distinction between cosmogony (origin science) and cosmology (operations science), with the former allowing for supernatural creation while the latter emphasizes the regularities of natural processes. 28 Hoyle, Sir Fred, and Chandra Wickramasinghe. Evolution from Space. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. Two non-Christian scientists correctly argue that life could not have arisen on earth by itself. Instead of admitting to the creationist alternative, however, they suggest life was seeded on earth by aliens from outer space (of course that just moves the problem of origins to another planet). An example of the unbelievable things an unbeliever will believe in order to remain an unbeliever! Morris, Henry M. The Biblical Basis for Modern Science. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1984. One of the best of Morris's many books defending young-earth creationism. Shows the biblical commitments of pioneer scientists and the biblical foundations of their disciplines. Should put to rest the objection that the Bible is irrelevant in scientific issues. Young, Davis A. Creation and the Flood. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1977. A Christian geologist takes the unusual position that the Genesis flood was global but "tranquil" (in support of the old earth view). Twenty years later, Young gave this position up and argued for a "local flood" (in The Biblical Flood: A Case Study of the Church’s Response to Extrabiblical Evidence. Carlisle: The Paternoster Press, 1995). Individual professors may give instructions that differ from this sample. Please check with your instructor to make sure that you are writing the bibliography, as he wants it written. N.B. 29 Appendix A: A Complete Paper in Turabian 30 DMPA 800: PERSONAL ASSESSMENT AND ORIENTATION Complete Submission Fortune and Fortune: Discover Your God-Given Gifts McRae: The Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts ____________________ Submitted to Luther Rice Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry ____________________ Marvin M. P. Mullins P. O. Box 123 Romeo, FL 54321 I.D.# AB1234 / Phone: (987) 222-3210 January 3, 2003 Advisor: Dr. Langford Professor: Dr. Kinnebrew Hours Completed: 3 -- Hours Remaining: 33 HELL: THE NECESSITY AND NATURE OF DIVINE RETRIBUTION ____________________ A Paper Presented to Dr. James Kinnebrew Luther Rice Seminary ____________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Course DMPA 800-D Personal Assessment and Orientation ____________________ by Marvin M. P. Mullins AB 1234 OUTLINE I. II. INTRODUCTION HELL: A. B. III. IV. THE NECESSITY AND NATURE OF DIVINE RETRIBUTION The Necessity of Hell The Nature of Hell CONCLUSION SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY ii INTRODUCTION Is a belief in Hell necessary? This is a question which rages not only in many quasi-Christian cults, but also in liberal elements of supposedly Bible-believing churches and denominations. This paper will demonstrate that the Bible teaches the reality and necessity of Hell. Further, it will provide insights about the nature of Hell and what kind of place it is. In this short paper the doctrine of Hell will be examined with an interest in these specific concerns. This is by no means an exhaustive list of subjects related to Hell, but this essay will confine itself to these considerations. 1 HELL: THE NECESSITY AND NATURE OF DIVINE RETRIBUTION The Necessity of Hell Many have argued that a belief in Hell is unnecessary. Some who call themselves Christians, including pastors and denominational leaders, say that they believe the Bible, yet they do not acknowledge Hell's reality. Many cults that present themselves as Christian teach that belief in Hell's existence is erroneous or inappropriate. As A. T. Hanson stated in A Dictionary of Christian Theology, "The weakening of belief in the verbal inspiration of the Bible has meant that hell fire has largely disappeared from the theological scene."1 Still, one notes at least three reasons to believe, proclaim, and defend this doctrine. First, the Old Testament states, "And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, Some to everlasting life, Some to shame and everlasting contempt" (Dan 12.2).2 The Gospel writer records in Matt 25.46, "And ____________________ 1 Alan Richardson, ed., A Dictionary of Christian Theology [DCT], s.v. "Heaven and Hell," by A. T. Hanson, 151. 2 Unless otherwise stated, the New King James Version will be used consistently throughout this paper. 2 these will go away into everlasting punishment, but the righteous into eternal life." Also, the final book of the Bible asserts, "And anyone not found written in the Book of Life was cast into the lake of fire" (Rev 20.15). Even a casual reading of the Word of God leads to the inescapable conclusion that Hell is a biblical reality. Further, Hell was taught by the Lord Jesus Himself. Though some have posited that the idea of Hell is antithetical to the "sweet" nature and teachings of Jesus, most of the Bible's teaching on Hell comes from the lips of Christ. W. T. Conner argued: Nobody teaches this more clearly and emphatically than does Jesus. He solemnly and repeatedly warns men against the dangers of a hell of fire in which God will destroy both soul and body (Matt. 5:22,29; 10:28; 18:9; Mark 9:43,45; Luke 12:5, et al.).3 Finally, logic and the existence of a moral order demand that there be a Hell.4 In Acts 1.25 the Bible states that Judas, after he died, went to "his own place." An eternal place exists for everyone, and it cannot be the same for the holy and the sinful, the forgiven and those who die without forgiveness, the Hitler and the Corrie Ten Boom. Since God created a moral order in the world, punishment for sinners is a logical extrapolation. ____________________ The man who chooses to 3 W. T. Conner, Christian Doctrine (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1937), 326-37. 4 A. H. Strong, Systematic Theology (Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1907), 1049. 3 live in sin in this life can never be happy in God's presence and must be separated from God and Heaven forever. Many men think that if they can just stay out of the fire after they die they will be all right. What they need to see is that they must get the fire of sin out of their souls.5 Therefore, Holy Scripture, the Lord Jesus Christ, and the very existence of a moral order in a logical universe demand the necessity of a Hell. The question now may be asked, what can be learned about the nature of Hell? The Nature of Hell To understand fully the kind of awful abode that Hell is, one must first see it as a place of demons. The Bible states, "And the angels who did not keep their proper domain, but left their own abode, He has reserved in everlasting chains under darkness for the judgment of the great day" (Jude 6). Also, the Book of Revelation speaks of a "pit" and a "lake of fire" which will be populated by fallen angels.6 Second, Hell is seen as a place of distress. The Scholastics spoke of poena sensus, or "some sort of external agent of torment."7 ____________________ 5 Conner, Christian Doctrine, 327. 6 Strong, Systematic Theology, 450. 7 Richardson, DCT, 151. 4 The Son of Man will send out His angels, and they will gather out of His kingdom all things that offend, and those who practice lawlessness, and will cast them into the furnace of fire. There will be wailing and gnashing of teeth (Matt 13.41-42). Other Scriptures associate Hell with everlasting punishment (2 Thes 1.8-9), fire and brimstone (Rev 14.10), unquenchable fire (Mark 9.44), and tribulation (Matt 24.21).8 Third, Hell is seen as a place of deprivation. The unrighteous are said by the Scriptures to be separated from the righteous (Matt 13.49), from light (Matt 25.30), and from rest (Rev 14.11).9 Surely, though, the worst of all isolations is that referred to by the scholastics as poena damni, or “the sense of separation from God.”10 Fourth, Hell is seen as a place of debts coming due. The Bible is clear that “God is not mocked; for whatever a man sows, that will he also reap” (Gal 6.7). It further declares that “the wages of sin is death” (Rom 6.23) and “the soul who sins shall die” (Ezek 18.4). Paul said: But in accordance with your hardness and your impenitent heart you are treasuring up . . . wrath in the day of _________________________ 8 James P. Boyce, Abstract of Systematic Theology (Pompano Beach, FL: Christian Gospel Foundation reprint, n.d.), 477. 9 Ibid., 478. 10 Richardson, DCT, 151. 5 wrath and revelation of the righteous judgment of God (Rom 2.5). Hell, therefore, is a place where the justice and judgment of God finally are satisfied. Sin has as an integral part of its nature a price that must be paid. W. T. Conner has stated the point as follows: Men are punished in this life for their sins. That is made clear in the examples and teachings of the Bible. It is also verified in experience. But men do not get the full punishment for their sins in this life. The full punishment for sin, therefore, must come in the next life.11 Finally, Hell is seen as a place of duration. Each of the foregoing facets of Hell’s nature has been confirmed by scholars based on the character of man and the character of man’s sin. But it is the character of God that clearly necessitates the eternality of Hell. Augustus H. Strong goes so far as to compare the ceaseless nature of Hell to the infinite nature of the Trinity, the abiding presence of the Holy Spirit with Christians, and the endlessness of the saint’s abode in Heaven.12 _________________________ 11 Conner, Christian Doctrine, 326. 12 Strong, Systematic Theology, 1044-46. 6 CONCLUSION The scope of this examination has not allowed more than a terse synopsis of this weighty doctrine. However, even the most fleeting glance at the biblical evidence should convince the honest seeker of the aforementioned truths about Hell. To review, biblical and intellectual honesty insist on a belief in Hell. The Holy Scriptures and logic demand it, and the Lord Jesus verified it. Finally, this writer believes that Hell can be described as a place of demons, distress, deprivation, debts coming due, and duration. Language about hell seeks to describe for humans the most awful punishment human language can describe to warn unbelievers before it is too late. . . . Certainly, no one wants to suffer the punishment of hell, and through God’s grace the way for all is open to avoid hell and know the blessings of eternal life through Christ.13 These words of Ralph L. Smith provide an appropriately gripping conclusion to such an imposing study. _______________________ 13 Trent C. Butler, ed., Holman Bible Dictionary, s.v. “Hell,” by Ralph L. Smith, 632. 7 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Boyce, James P. Abstract of Systematic Theology. Rep. ed. Pompano Beach, FL: Christian Gospel Foundation, n.d. Bray, Gerald. “Hell: Eternal Punishment or Total Annihilation?” Evangel 10(Summer 1992): 19-24. Butler, Trent C., ed. Holman Bible Dictionary. Nashville: Holman Bible Publishers, 1991. S.v. "Hell," by Ralph L. Smith. Conner, W. T. Christian Doctrine. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1937. Edwards, David L. and John R. W. Stott. Evangelical Essentials. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1988. The Holy Bible. New King James Version. Richardson, Alan, ed. A Dictionary of Christian Theology. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1969. S.v. "Heaven and Hell," by A. T. Hanson. Strong, Augustus H. Systematic Theology. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1907. 8

© Copyright 2026