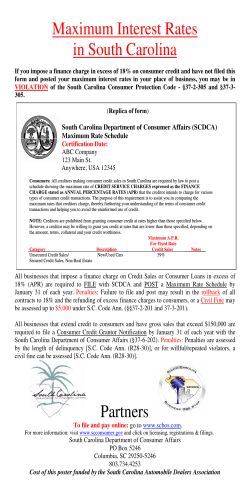

Document 266266