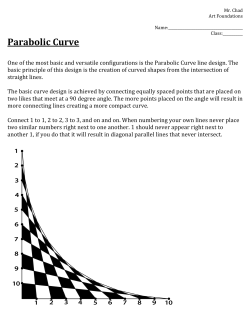

sample only ECONOMIC FUNDAMENTALS IN