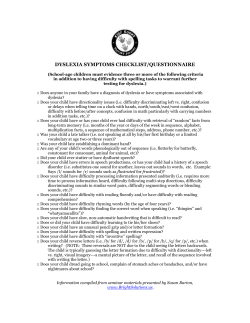

SAMPLE CHAPTER 7 STRATEGIES FOR TEACHING STUDENTS WITH LEARNING AND BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS, 7/E