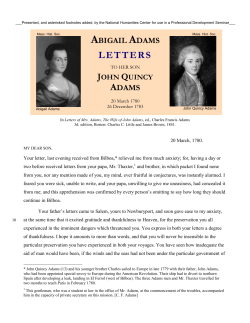

Abigail Adams, the Writer: “My pen is always freer than my tongue.”