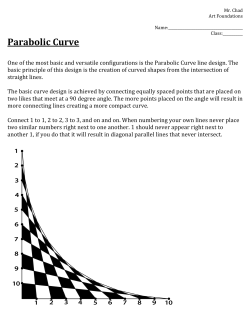

Sample Packet for: Tim Taylor’s Includes: