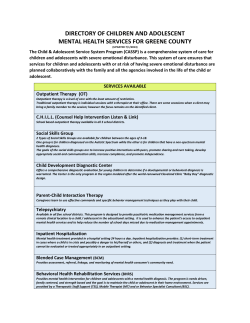

INFLUENCES IN HOME, SCHOOL AND COMMUNITY ENVIRONMENTS