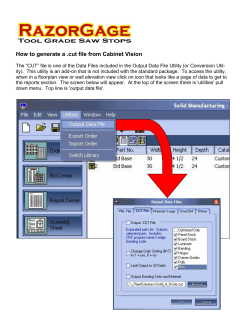

The Cabinet Manual A guide to laws, conventions