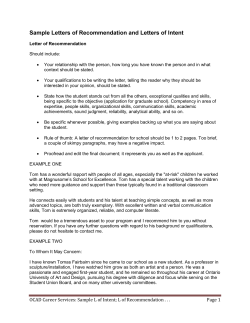

Letters of Intent The University of Texas School of Law