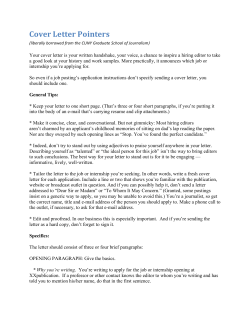

IN THIS ISSUE