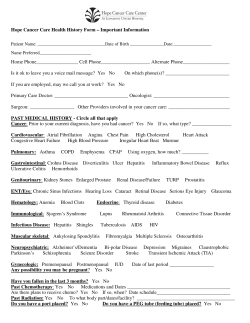

Patients With COPD in Each Cardiovascular Risk Category Prescribed an... Statin, or Other Anticoagulant

Table 1—Patients With COPD in Each Cardiovascular Risk Category Prescribed an Antiplatelet Drug, Statin, or Other Anticoagulant No Established CVD Drug Antiplatelet Statin Other anticoagulant Established CVD (n 5 32) Estimated 10-y CV Risk . 20% (n 5 32) Estimated 10-y CV Risk 10%-20% (n 5 26) Estimated 10-y CV Risk , 10% (n 5 27) 22 (69) 17 (53) 8 (25) 19 (59) 7 (22) 6 (19) 3 (12) 12 (46) 4 (15) 8 (30) 3 (11) 1 (7) Data presented as No. (%). CV 5 cardiovascular; CVD 5 cardiovascular disease. Low rates of statin and aspirin prescribing in patients with both COPD and increased cardiovascular risk imply that CVD is considered too infrequently in this group. Because COPD itself may well be an additional risk factor for CVD, it follows that statin therapy, along with other interventions to modify cardiovascular risk, is especially important in this complex group.1 Richard D. Turner, MBChB Charles M. Gwavava, MBChB Stephen M. Bianchi, PhD Sheffield, England Affiliations: From the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article. Correspondence to: Richard D. Turner, MBChB, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Herries Rd, Sheffield, S5 7AU, England; e-mail: [email protected] © 2011 American College of Chest Physicians. Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (http://www.chestpubs.org/ site/misc/reprints.xhtml). DOI: 10.1378/chest.11-0887 References 1. Nussbaumer-Ochsner Y, Rabe KF. Systemic manifestations of COPD. Chest. 2011;139(1):165-173. 2. British Cardiac Society; British Hypertension Society; Diabetes UK; HEART UK; Primary Care Cardiovascular Society; Stroke Association. JBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart. 2005;91(suppl 5):v1-v52. 3. Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, et al; American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. AHA guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke: 2002 update: consensus panel guide to comprehensive risk reduction for adult patients without coronary or other atherosclerotic vascular diseases. Circulation. 2002;106(3):388-391. 4. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al; Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative metaanalysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1849-1860. 5. Taylor F, Ward K, Moore TH, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(1):CD004816. 1386 Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/21/2014 Chest Ultrasonography as a Replacement for Chest Radiography in the ED To the Editor: The study by Zanobetti et al1 in a recent issue of CHEST (May 2011) proposes chest ultrasonography as a replacement for chest radiography as the initial imaging modality in the ED. Although the superior sensitivity of ultrasonography over chest radiography for assessment of effusion is acknowledged and in keeping with previous studies,2 there are a number of caveats to using ultrasonography in favor of chest radiography as a firstline imaging test. First, the training required for detecting the sonographic features of pneumothorax, localized atelectasis, and pulmonary fibrosis is extensive, and probably requires at least level 2 Royal College of Radiology training in chest ultrasonography in the United Kingdom (if not level 3, which would be equivalent to a radiologist).3 In addition, acquisition and interpretation of sonographic images is notoriously operator dependent, unlike interpretation of chest radiographs or CT images. This also presents issues with how a critical mass of operators who are adequately trained can be generated for the ED environment. Second, acquisition of ultrasound equipment has cost implications for financially rationed health-care systems. This usually requires the demonstration of cost utility, which may be demonstrable for effusions4 but not the other conditions encountered in the study, on the basis of its performance against chest radiography. Third, in the detection of pneumothorax, the chest radiograph (unlike ultrasonography) provides useful ancillary information as to the anatomic extent and location of most pneumothoraces (unless too small to be visible, in which case CT scan is needed). Many guidelines use the chest radiograph appearance in pneumothorax to guide further management.5 Finally, the chest radiograph may also give useful ancillary information not available from the ultrasonograph (eg, a more central lung neoplasm, mediastinal adenopathy, or a dilated right interlobar pulmonary artery suggesting pulmonary hypertension). In summary, chest ultrasonography has many applications,6 especially in the assessment of pleural effusion, but it should not replace the chest radiograph as a first-line imaging test in the assessment of acutely dyspneic patients presenting to the ED. Andrew R. L. Medford, MBChB, MD, FCCP Bristol, England Affiliations: From the North Bristol Lung Centre, Southmead Hospital. Correspondence Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The author has reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article. Correspondence to: Andrew R. L. Medford, MBChB, MD, FCCP, North Bristol Lung Centre, Southmead Hospital, Westbury-onTrym, Bristol, BS10 5NB, England; e-mail: andrewmedford@ hotmail.com © 2011 American College of Chest Physicians. Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (http://www.chestpubs.org/ site/misc/reprints.xhtml). DOI: 10.1378/chest.11-1403 References 1. Zanobetti M, Poggioni C, Pini R. Can chest ultrasonography replace standard chest radiography for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED? Chest. 2011;139(5):1140-1147. 2. Eibenberger KL, Dock WI, Ammann ME, Dorffner R, Hörmann MF, Grabenwöger F. Quantification of pleural effusions: sonography versus radiography. Radiology. 1994; 191(3):681-684. 3. Royal College of Radiologists. Ultrasound training recommendations for medical and surgical specialties. Ref No: BFCR (05)2. Royal College of Radiologists Web site. http://www.rcr.ac.uk/ docs/radiology/pdf/ultrasound.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed May 6, 2011. 4. Medford AR. Additional cost benefits of chest physicianoperated thoracic ultrasound (TUS) prior to medical thoracoscopy (MT). Respir Med. 2010;104(7):1077-1078. 5. MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65(suppl 2):ii18-ii31. 6. Medford AR, Entwisle JJ. Indications for thoracic ultrasound in chest medicine: an observational study. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86(1011):8-11. the core educational program for all emergency medicine residency programs, in a few years all new emergency physicians will have the required competency, and a critical mass of operators will be available in the ED. Obviously, as for all novel developments, a delay is inevitable before a widespread diffusion of the new methodology is realized. Regarding the costs associated with the use of ultrasonography in the ED, at least in our experience, almost all EDs had ultrasound equipment. However, as suggested by Dr Medford, further studies must be performed to demonstrate the cost/effectiveness of CUS vs chest radiography. Regarding the detection of pneumothorax, several data demonstrated that small pneumothorax can be missed by bedside radiography but detected by CUS and subsequently confirmed by chest CT scan.3,4 In conclusion, we never stated that chest radiography can be eliminated from the workout of a patient with dypsnea, but our data support the hypothesis that CUS can be a reliable modality for the initial clinical evaluation of these patients in the ED. Maurizio Zanobetti, MD Claudio Poggioni, MD Riccardo Pini, MD Florence, Italy Affiliations: From the Intensive Observation Unit, Careggi University Hospital, and Department of Critical Care Medicine and Surgery, University of Florence. Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article. Correspondence to: Maurizio Zanobetti, MD, Intensive Observation Unit, Careggi University Hospital, and Department of Critical Care Medicine and Surgery, University of Florence, Largo Brambilla, 3, 50134 Florence, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] © 2011 American College of Chest Physicians. Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (http://www.chestpubs.org/ site/misc/reprints.xhtml). DOI: 10.1378/chest.11-1649 Response References To the Editor: We thank Dr Medford for his thoughtful comments on our article regarding the use of chest ultrasonography (CUS) in the ED.1 In his letter, Dr Medford expressed some concerns for the use of CUS before chest radiography as a first-line imaging test. In general, we would agree with Dr Medford’s concerns if we had proposed the use of CUS in general clinical practice, but we limited the use of this diagnostic tool as a first-line screening modality in the ED. As a consequence, we never proposed the replacement of chest radiography with CUS in the clinical management of all chest/lung diseases. Instead, we presented data supporting the advantages of ultrasonography (eg, less time consuming, absence of ionizing radiations) in the initial evaluation of patients presenting in the ED with acute dyspnea. Due to this limited and focused use of CUS, the training required to achieve clinical competence is probably shorter than the training suggested by Dr Medford. In effect, the American College of Emergency Physicians Emergency Ultrasound Guidelines2 propose a 1-day introductory course and a minimum 2-week rotation; a minimum of 150 ultrasound examinations must be performed to acquire a sufficient level of competency. This training duration seems to be significantly shorter than the training duration proposed by the Royal College of Radiology. If, as suggested by the American College of Emergency Physicians, emergency ultrasonography education is incorporated into www.chestpubs.org Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/21/2014 1. Zanobetti M, Poggioni C, Pini R. Can chest ultrasonography replace standard chest radiography for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED? Chest. 2011;139(5):1140-1147. 2. American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency ultrasound guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(4):550-570. 3. Lichtenstein DA, Mezière G, Lascols N, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of occult pneumothorax. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(6): 1231-1238. 4. Volpicelli G. Sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(2):224-232. Lung Transplantation in Coal Workers Pneumoconiosis To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Wade et al1 in a recent issue of CHEST (June 2011). The authors reviewed the records of 138 coal miners who were diagnosed with coal workers pneumoconiosis (CWP) and developed evidence of progressive massive fibrosis (PMF). The authors reported that several patients had a rapid progression of the disease (5-12 years) and reported 21 deaths (15%) in the cohort during the study period. CHEST / 140 / 5 / NOVEMBER, 2011 1387

© Copyright 2026