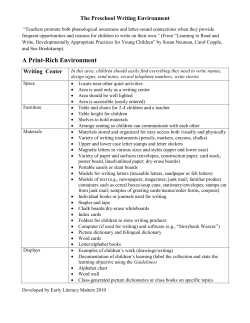

First 5 Special Study of High-Quality Preschools Case Study Reports __________________________________________