Catheter-Tract Metastases

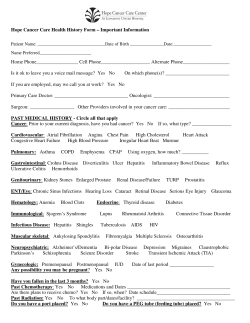

CHEST Catheter-Tract Metastases Associated With Chronic Indwelling Pleural Catheters* Sam M. Janes, MBBS, PhD, MRCP; Najib M. Rahman, BM BCh, MA, MRCP; Robert J. O. Davies, DM, FRCP; and Y. C. Gary Lee, MBChB, PhD, FCCP Indwelling pleural catheters are increasingly being used for ambulatory treatment of malignant pleural effusion, particularly for patients unsuitable for pleurodesis. These catheters are often left in situ for the rest of the patient’s life. Tumor metastasis along the tract between pleura and skin surface is a potential complication in patients with chronic indwelling pleural catheters that has seldom been reported. We describe four cases of catheter-tract metastasis that developed between 3 weeks and 9 months after catheter insertion. Catheter-tract metastasis occurred in two patients with mesothelioma despite prophylactic irradiation at time of insertion, and in two patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma. All cases were successfully treated using external-beam radiotherapy without necessitating catheter removal. A retrospective audit in our center showed that catheter-tract metastasis occurred in 6.7% of 45 patients treated with indwelling pleural catheters for *From the Centre of Respiratory Research (Drs. Janes and Lee), University College London, UK; and Oxford Pleural Unit (Drs. Rahman and Davies), Oxford Centre for Respiratory Medicine and University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Dr. Janes is supported by a Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist Fellowship, Dr. Lee is supported by a Wellcome Advanced Fellowship, and Dr. Rahman is supported by a Medical Research Council Training Fellowship. Drs. Janes and Rahman do not have any conflict of interests or involvement with organizations with financial interests in the subject matter. Drs. Davies and Lee have been awarded a project grant from the British Lung Foundation to compare conventional pleurodesis with chronic indwelling pleural catheters in patients with malignant pleural effusions. The investigators of the trial have accepted an arrangement to use pleural catheters provided for free by Rocket Med plc (UK), since the acceptance of this manuscript for publication. None of the investigators received any funding from the company. Manuscript received September 24, 2006; revision accepted November 10, 2006. Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal. org/misc/reprints.shtml). Correspondence to: Y. C. Gary Lee, MBChB, PhD, FCCP, Oxford Centre for Respiratory Medicine, Churchill Hospital, Oxford OX3 7LJ, UK; e-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.1378/chest.06-2353 1232 Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 Selected Reports malignant pleural effusions. Both clinicians and patients should be aware of this potential complication. (CHEST 2007; 131:1232–1234) Key words: adenocarcinoma; indwelling catheter; mesothelioma; metastases; pleura pleural effusions are common in clinical M alignant practice. Indwelling pleural catheters have increas1 ingly been advocated for management of recurrent effusions, especially in patients unsuitable for pleurodesis, or in whom pleurodesis has failed.1–5 These catheters are often left in situ for the rest of the patient’s life. Tumor metastases from the parietal pleura to the skin surface following tracts from pleural procedures (eg, thoracoscopy) are known complications of mesothelioma but are rare with other malignancies.1 Patients with chronic indwelling pleural catheters are at continual risks of tumor spread along catheter tracts. Catheter-tract metastasis has seldom been reported, and its incidence is unclear. We report a series of four patients with catheter-tract metastasis from indwelling pleural catheters: two patients with adenocarcinoma, and two patients with mesothelioma. Case Report A large left pleural effusion developed in a 61-year-old woman (Fig 1, 2) 4 months after a left pneumonectomy and chest wall Figure 1. Chest radiograph from the initial presentation showing a large left pleural effusion in the postpneumonectomy space. Selected Reports Retrospective Audit The above case prompted a retrospective audit of the incidence of catheter-tract metastases from indwelling PleurX catheters in the Oxford Pleural Unit. Between June 2002 and February 2006, 45 PleurX catheters were inserted for drainage of malignant pleural effusions. All patients were followed up by the unit, and any cathetertract metastases were recorded. Catheter-tract metastasis developed in 3 of 45 patients (6.7%) [Table 1]. The incidence appeared higher in mesothelioma patients (2 of 15 patients, 13.3%) than in those with metastatic carcinomas (1 of 30 patients, 3.3%). Both of the patients with mesothelioma had such metastases despite prophylactic irradiation within 2 weeks of catheter placement. Tract metastasis developed after 6 months in two patients and 9 months in the third patient. All three patients were successfully treated with radiotherapy with the drain in situ, and the indwelling catheters continued to function well. Figure 2. Contrast-enhanced thoracic CT scan demonstrating diffuse tumor involvement of the pleural surface. resection for lung adenocarcinoma and preoperative chemotherapy. She had significant symptomatic relief after drainage of pleural fluid, which tested positive for malignant cells. Despite second-line chemotherapy with docetaxel, the effusion reaccumulated rapidly and required frequent drainage. Given the prior pneumonectomy, pleurodesis was regarded as inappropriate. Instead, a small-bore indwelling pleural catheter (PleurX; Denver Biomedical; Golden, CO) was inserted for ambulatory fluid drainage, with good symptomatic effect. Three weeks later, a tumor nodule developed (Fig 3) at the catheter insertion site. This was treated with external-beam radiotherapy (21Gy in three fractions) administered while the catheter remained in situ. Radiotherapy did not affect the function of the catheter. The nodule resolved and was replaced by scar tissue 2 weeks after irradiation. No new nodules developed in the subsequent 3 months of follow-up. Figure 3. Tumor nodule growing through the chest wall at the indwelling catheter site. www.chestjournal.org Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 Discussion We report four cases of catheter-tract metastasis in patients with pleural malignancies managed with indwelling pleural catheters. Our series include two cases of tract metastasis from adenocarcinomas: a complication seldom reported with cancers other than mesothelioma. In addition, we have shown that catheter-tract metastasis can be treated with external-beam irradiation with the catheter in situ. Prophylactic radiotherapy to the insertion site did not prevent metastasis from indwelling catheters in the two patients with mesothelioma. Ambulatory drainage of recurrent malignant effusions using small-bore indwelling pleural catheters is increasingly used worldwide for the management of malignant pleural effusions, especially in patients who failed pleurodesis, have trapped lungs, or have a limited life expectancy.1 The use of these catheters is generally safe, but the full spectrum of potential side effects has not been established. The parietal pleura is often affected in malignant pleural diseases.1 Needle tract metastasis along previous pleural puncture sites is well established with mesothelioma, and occurs in up to 40% of patients.5 However, metastasis from adenocarcinomas along pleural puncture sites are uncommon. Catheter-tract metastasis with indwelling pleural catheters has rarely been reported. In three large series of a combined 374 patients,2– 4 only two cases were described. In our population, catheter-tract metastasis occurred in 6.7% of patients who received PleurX catheters. Prophylactic irradiation of the pleural puncture sites is effective in preventing needle tract metastases from mesothelioma following “one-off” pleural procedures (eg, thoracostomy or thoracoscopy). However, radiotherapy may offer limited protection against ongoing risks of malignant invasion in patients with long-term indwelling pleural catheters. This may explain the development of catheter-tract metastases despite prophylactic radiotherapy in our two mesothelioma patients. External-beam radiotherapy was effective in treating CHEST / 131 / 4 / APRIL, 2007 1233 Table 1—Details of the Three Patients With Catheter-Tract Metastasis From the Retrospective Audit Patient No. Histologic Tumor Type Insertion of PleurX Catheter After Diagnosis, mo Tract Metastasis After Insertion, mo Prophylactic Radiotherapy 1 Mesothelioma 1.5 10 d after PleurX insertion 7 2 Epithelioid mesothelioma 1 9 3 Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of unknown primary 5 d after PleurX insertion Not given 11 the catheter-tract metastases. Irradiation was performed with the catheter in situ without impairing the catheter drainage. In summary, catheter-tract metastasis can develop with both metastatic carcinomas and mesothelioma. The incidence is frequent enough that patients should be warned of this potential complication. Larger series are required to establish the incidence and risk factors for cathetertract metastasis. References 1 Lee YCG, Light RW. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Respirology 2004; 9:148 –156 2 Tremblay A, Michaud G. Single-center experience with 250 tunnelled pleural catheter insertions for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2006; 129:362–368 3 Putnam JB Jr, Walsh GL, Swisher SG, et al. Outpatient management of malignant pleural effusion by a chronic indwelling pleural catheter. Ann Thorac Surg 2000; 69:369 – 375 4 Musani AI, Haas AR, Seijo L, et al. Outpatient management of malignant pleural effusions with small-bore, tunneled pleural catheters. Respiration 2004; 71:559 –566 5 Boutin C, Rey F, Viallat JR. Prevention of malignant seeding after invasive diagnostic procedures in patients with pleural mesothelioma: a randomized trial of local radiotherapy. Chest 1995; 108:754 –758 8 Treatment for Tract Metastasis Time of Death After Insertion, mo Radiotherapy at 30 Gy in six fractions (2 mo after initial metastasis) Low-dose palliative radiotherapy Radiotherapy (30 Gy in six fractions) and catheter removal 2 mo after initial metastasis 17 12 22 pneumonia-like symptoms that did not respond to treatment with antibiotics. Their chest radiographs revealed bilateral diffuse infiltrates. The diagnosis of AEP was established based on the clinical picture, BAL that revealed an average eosinophil count > 45%, and immediate clinical improvement after introducing corticosteroids. All other possible causes were excluded during the initial workup. (CHEST 2007; 131:1234 –1237) Key words: eosinophils; pneumonia; smoking Abbreviation: AEP ⫽ acute eeosinophilic pneumonia eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) is characterized A bycuteeosinophilic infiltration in the lungs, respiratory distress, a rapid therapeutic response to corticosteroids, and the absence of relapse.1 Cigarette smoking has been recognized to cause AEP, and a report2 from Japan has demonstrated an association of cigarette smoking-induced AEP with menthol-flavored cigarettes. Based on review of two cases of AEP following flavored cigar smoking, we believe that the flavoring component may have a major rule in precipitating the illness. Case Reports Case 1 Flavored Cigar Smoking Induces Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia* Nawar Al-Saieg, MD; Ousama Moammar, MD; and Ritha Kartan, MD, FCCP Two cases of acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) following smoking of flavored cigars were analyzed for characteristic features. None of our patients had a history of smoking flavored cigars/cigarettes in the past. One of them had never smoked, and the second patient was an ex-smoker who quit 17 years ago. Both patients presented with community-acquired 1234 Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 A previously healthy 23-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 5-day history of shortness of breath and exercise intolerance. The patient reported a relatively sudden onset of a *From the Department of Internal Medicine, Western Reserve Care System/Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, Youngstown, OH. This work was performed at Western Reserve Care System, Youngstown, OH. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Manuscript received October 27, 2006; revision accepted November 21, 2006. Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal. org/misc/reprints.shtml). Correspondence to: Nawar Al-Saieg, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Western Reserve Care System, 500 Gypsy Ln, Youngstown, OH 44501; e-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.1378/chest.06-2623 Selected Reports Figure 1. Chest CT showing a small, right-sided pleural effusion, minimal pleural reaction on the left, and patchy parenchymal infiltrates in both lung fields. productive cough of yellowish sputum accompanied by fever, chills, and dyspnea on minimal exertions. The patient also reported mild headache, loss of appetite, and generalized weakness prior to hospital admission. The patient started smoking strawberry-flavored cigars 3 weeks prior to admission, approximately four cigars weekly. There was no history of any other form of tobacco or alcohol abuse or any recreational drug use. In the emergency department, the patient had a temperature of 38.3°C, BP was 129/74 mm Hg, pulse rate was 126 beats/min, and respiration rate was 22 breaths/min. Blood oxygen saturation was 88% on room air. Physical examination showed coarse crackles posteriorly in both lungs. There was no use of accessory muscles. Laboratory findings revealed WBC count of 14,250/L; polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 75%; lymphocytes, 10%; eosinophils, 8%; and monocytes, 3%. By hospital day 5, eosinophil fraction had increased to 26%. Chest radiography showed diffuse bilateral pulmonary infiltrates. The chest CT showed a small rightsided pleural effusion, minimal pleural reaction on the left and Figure 2. Chest radiograph showing diffuse bilateral infiltrate greater on the right side. www.chestjournal.org Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 Figure 3. CT of the chest revealing bilateral diffuse infiltrates with small bilateral pleural effusions. patchy parenchymal infiltrates in both lung fields (Fig 1). The patient was started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin and then was switched to moxifloxacin without any improvement. Video bronchoscopy was performed and showed diffuse inflammation with copious watery secretions. There was no evidence of endobronchial tumors. BAL showed nucleated cells at 738/L; eosinophils, 72%; and lymphocytes, 15%. All bacterial, viral, and fungal study results were negative. The patient received IV methylprednisolone after stopping antibiotics and improved dramatically within 24 h. Chest radiography demonstrated remarkable resolution of the infiltrates after steroids. The patient was discharged on a tapering dose of oral prednisone. Case 2 The second case was a 53-year-old white man with a medical history significant for coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus type 2, and hypercholesterolemia. A history of allergy to strawberries was reported. The patient presented to the emergency department with Figure 4. Chest radiograph revealing remarkable resolution of the infiltrates. CHEST / 131 / 4 / APRIL, 2007 1235 a 2-day history of chest tightness, dry cough, and dyspnea. He reported a new onset of night sweats, chills, and wheezing. The patient denied any sick contact, recent travel, or weight loss. The patient visited his family doctor’s office 3 days prior to hospital admission and was started on azithromycin without any improvement. He quit smoking 17 years ago, but 3 weeks prior to hospital admission he restarted smoking different types of flavored cigars. On examination, the patient was found to be febrile with a temperature of 38.1°C, a heart rate of 120 beats/min, and blood oxygen saturation of 92% on 3 L/min of oxygen; later on, the oxygen saturation went down and the patient required 100% oxygen. Lung examination revealed bilateral crackles. There was no use of accessory muscles. Laboratory findings were WBC count of 17,400/L; polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 91%; lymphocytes, 1%; eosinophils, 4%; and monocytes, 2%. By hospital day 5, eosinophil fraction had increased to 33%. Diffuse bilateral infiltrate greater on the right side was noted on chest radiograph (Fig 2). CT of the chest revealed bilateral diffuse infiltrates with small bilateral pleural effusions (Fig 3). At that point, the patient was admitted to the hospital and treated for community-acquired pneumonia with moxifloxacin without improvement. Video bronchoscopy clearly showed an inflamed mucosa of the left bronchial tree. There was no mass or any evidence of consolidation. BAL showed nucleated cells at 31,500/L; eosinophils, 49%; and lymphocytes, 16%. The patient was started on IV methylprednisolone and improved dramatically after introducing the steroid treatment. Chest radiography revealed remarkable resolution of the infiltrates in the next few days (Fig 4). The patient was discharged on a tapering dose of oral prednisone. Discussion The cause of AEP remains unknown. Some investigators3 have suggested that AEP is an acute hypersensitivity reaction to an unidentified inhaled antigen. Patients usually present with an acute febrile illness of ⬍ 3 weeks in duration, and in most cases the duration of symptoms is ⬍ 7 days. Nonproductive cough and dyspnea are present in almost every patient. Associated symptoms and signs include malaise, myalgias, night sweats, pleuritic chest pain, and hypoxemic respiratory insufficiency. Physical examination usually shows fever and tachypnea. Bibasilar inspiratory crackles and occasionally rhonchi on forced exhalation are heard on auscultation of the chest.4,5 Patients generally present with an initial neutrophilic leukocytosis.2,6 In most cases, the eosinophil count becomes markedly elevated during the subsequent course of AEP.5–7 Patients with AEP are uniformly responsive to IV or oral corticosteroid therapy.5 The response is often dramatic, occurring within 12 to 48 h, and there is no relapse following withdrawal of the steroids. The present two cases met the criteria for a diagnosis of AEP by Allen and Davis8: an acute febrile illness of short duration (usually ⬍ 1 week), hypoxemic respiratory failure, diffuse pulmonary opacities on chest radiograph, BAL eosinophilia ⬎ 25%, lung biopsy evidence of eosinophilic infiltrates, and absence of known causes of eosinophilic pneumonia, including drugs, infections, or asthma. We have excluded all possible causes in the initial workup. In reviewing the literature, one study2 reported flavored cigarettes, specifically menthol flavored, as the underlying cause of cigarette smoking-associated AEP. Other reports have associated AEP with World Trade Center dust exposure,9 as well as military personnel having this complication in Iraq after significant exposure to fine airborne sand or dust.10 In our first case, the patient was a nonsmoker and started 1236 Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 smoking flavored cigars for the first time 3 weeks prior to hospital admission. It is difficult in this case to make a clear assumption that AEP was most likely induced by the chemical substances used for flavoring the cigar. However, smoking itself could be the triggering factor of AEP, as it has been implicated in previous reports,11–14 and proven by a smoking challenge test. For that test, the patient was asked to smoke 20 cigarettes a day for 13 days. The challenge test reproduced typical BAL and transbronchial lung biopsy changes of AEP, but the patient had neither radiologic changes nor symptoms after the challenge test.15 We did not perform a smoking challenge test on our patients. The second patient was an ex-smoker and had no documented history of pneumonia. The patient stopped smoking 17 years ago and resumed smoking 3 weeks prior to hospital admission, trying different types of flavored cigars. Because of a longstanding history of smoking without any history of documented respiratory events related to smoking cigarettes, we suspected a major rule of flavoring components in inducing his AEP. These cases illustrate the increasing evidence that cigarette/cigar smoking could be indeed a major factor in inducing AEP. More importantly, it demonstrates the importance of a detailed medical and smoking history to identify flavored cigar as a probable cause of AEP. More extensive investigation and research is needed to reach a solid conclusion regarding the actual rule of flavoring cigar/cigarette in inducing AEP. References 1 Allen JN, Pacht ER, Gadek JE, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia as a reversible cause of noninfectious respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:569 –574 2 Miki K, Miki M, Nakamura Y, et al. Early-phase neutrophilia in cigarette smoke induced acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Intern Med 2003; 42:839 – 845 3 Badesch DB, King TE Jr, Schwarz MI. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia: a hypersensitivity phenomenon? Am Rev Respir Dis 1989; 139:249 –252 4 Ogawa H, Fujimura M, Matsuda T, et al. Transient wheeze: eosinophilic bronchobronchiolitis in acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Chest 1993; 104:493– 496 5 Jantz MA, Sahn SA. Corticosteroids in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:1079 –1100 6 Philit F, Etienne-Mastroianni B, Parrot A, et al. Idiopathic acute eosinophilic pneumonia: a study of 22 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166:1235–1239 7 Hayakawa H, Sato A, Toyoshima M, et al. A clinical study of idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia. Chest 1994; 105:1462– 1466 8 Allen JN, Davis WB. Eosinophilic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 150:1423–1438 9 Rom WN, Weiden M, Garcia R, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia in a New York City firefighter exposed to World Trade Center dust. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166:797– 800 10 Shorr AF, Scoville SL, Cersovsky SB, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia among US military personnel deployed in or near Iraq. JAMA 2004; 292:2997–3005 11 Shintani H, Fujimura M, Yasui M, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia caused by cigarette smoking. Intern Med 2000; 39:66 – 68 12 Shiota Y, Kawai T, Matsumoto H, et al. Acute eosinophilic Selected Reports pneumonia following cigarette smoking. Intern Med 2000; 39:830 – 833 13 Nakagome K, Kato J, Kubota S, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia induced by cigarette smoking [abstract in English]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 2000; 38:113–116 14 Godding V, Bodart E, Delos M, et al. Mechanisms of acute eosinophilic inflammation in a case of acute eosinophilic pneumonia in a 14-year-old girl. Clin Exp Allergy 1998; 28:504 –509 15 Watanabe K, Fujimura M, Kasahara K, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia following cigarette smoking: a case report including cigarette-smoking challenge test. Intern Med 2002; 41:1016 –1020 Corynebacterium ulcerans Infection of the Lung Mimicking the Histology of Churg-Strauss Syndrome* Key words: Churg-Strauss syndrome; Corynebacterium ulcerans; eosinophil Abbreviation: CSS ⫽ Churg-Strauss syndrome orynebacterium ulcerans is a veterinary pathogen. C Nearly all human cases are characterized by pharyn- geal infections mimicking classical diphtheria.1 Cases of C ulcerans infection in human lung are extremely rare.2,3 In this article, we present a case of C ulcerans infection with multiple lung cavities and nodules. Histologic findings mimicked Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS). All lung lesions responded dramatically to antibiotics, and the patient recovered. Case Report In October 2005, a 50-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for high-grade fever up to 39°C, productive cough, dyspnea on effort, general fatigue, and weight loss continuing from 2 weeks previously. He had a duodenal ulcer at 15 years of age but was otherwise healthy. Shin-ichi Nureki, MD, PhD; Eishi Miyazaki, MD, PhD; Osamu Matsuno, MD, PhD; Ryuichi Takenaka, MD; Masaru Ando, MD, PhD; Toshihide Kumamoto, MD, PhD; Tadao Nakano, PhD; Kiyofumi Ohkusu, PhD; and Takayuki Ezaki, MD, PhD We report the first case of pulmonary Corynebacterium ulcerans infection mimicking Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS). Productive cough, fever, general fatigue, and weight loss developed in a 50-year-old man. Laboratory data revealed prominent eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE. On chest images, multiple nodules and cavities were predominantly detected in the right lung. Histopathologic examination showed necrotizing granulomas and vasculitis with massive eosinophilic infiltration identical to the findings seen in CSS; however, clusters of Grampositive, coryneform rods were observed in the alveolar spaces. A toxigenic strain of C ulcerans was isolated from lung tissue. The patient was treated with antibiotics, and a favorable clinical course ensued. (CHEST 2007; 131:1237–1239) *From the Divisions of Pulmonary Disease (Drs. Nureki, Miyazaki, Matsuno, Takenaka, and Ando) and Neurology and Neuromuscular Disorders (Dr. Kumamoto), Third Department of Internal Medicine, Oita University Faculty of Medicine, and Clinical Laboratory Center of Oita University Hospital (Dr. Nakano), Yufu; and Department of Microbiology, Regeneration, and Advanced Medical Science (Drs. Ohkusu and Ezaki), Gifu University Graduate School of Medicine, Gifu, Japan. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Manuscript received September 22, 2006; revision accepted December 11, 2006. Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal. org/misc/reprints.shtml). Correspondence to: Shin-ichi Nureki, MD, PhD, Division of Pulmonary Disease, Third Department of Internal Medicine, Oita University Faculty of Medicine, 1–1 Idaigaoka, Hasama-machi, Yufu, Oita 879-5593, Japan; e-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.1378/chest.06-2346 www.chestjournal.org Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 Figure 1. Top, A: Posteroanterior chest radiograph showing multiple nodules and cavities, predominantly in the right lung. Bottom, B: Chest CT showing multiple cavity nodules associated with bronchiectasis. CHEST / 131 / 4 / APRIL, 2007 1237 On hospital admission, the patient’s temperature was 37.6°C (maximum, 39.3°C on the same day), pulse rate was 100 beats/ min, and respiratory rate was 16 breaths/min. Coarse crackles were heard over both lung fields. Laboratory data on hospital admission included WBC count of 26,500/L, with 50.4% neutrophils and 37.5% eosinophils, and C-reactive protein of 10.82 mg/dL. Serum IgE concentration was elevated to 1,424 IU/mL. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Blood, sputum, and BAL fluid cultures findings, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis and fungi, were negative. A chest radiograph showed multiple nodules and cavities predominantly in the right lung (Fig 1, top, A). Chest CT scans disclosed that cavities and nodules were associated with bronchiectasis (Fig 1, bottom, B). Video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy was performed as a diagnostic procedure after obtaining informed consent. Histologic examination revealed necrotizing granulomas and vasculitis associated with prominent eosinophilic infiltration (Fig 2, top left, A, top right, B, and bottom left, C). These findings were compatible with the histologic features of CSS in the lung; however, clusters of Gram-positive, coryneform rods were observed in the alveolar spaces (Fig 2, bottom right, D). Gram-positive, short coryneform bacteria were isolated from lung tissue. The Elek test and Vero cell assay, which are standard microbiology tests, and sequencing of the tox gene showed clearly that this strain of C ulcerans produced diphtheria toxin identical to that of Corynebacterium diphtheriae.4,5 The isolate was susceptible to clarithromycin, benzylpenicillin, and levofloxacin. Clarithromycin, 400 mg/d, was introduced and maintained. One week later, 1 million IU/d of benzylpenicillin was additionally administered IM for 2 weeks. Thereafter, 400 mg/d of levofloxacin was administered for 6 months. Without the use of immunosuppressant therapy, his symptoms gradually improved, with chest images demonstrating dramatic improvement in the lung nodules. The patient has been in good health during the 8-month follow-up period. Discussion Only two cases of lung disease caused by C ulcerans have been reported in the literature.2,3 As in the previous cases, necrotizing granulomas were observed in the lung. However, the current case had necrotizing angiitis with marked eosinophilic infiltration in the lung, which has not previously been reported. The histologic features of the lung in this case resemble CSS. However, the current case did not meet the criteria of CSS, as there was no history of bronchial asthma.6 Gram-positive, coryneform rods were identified in the alveolar spaces, and C ulcerans was isolated from tissue culture of the inflamed lung. The patient was successfully treated only with antibiotics, without any immunosuppressive agent, although CSS-generated inflammation usually requires intervention with highdose corticosteroid, sometimes in combination with cyclophosphamide. Hence, we concluded that the CSS- Figure 2. Lung biopsy specimen obtained by video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy. Top left, A: Nodules show central necrosis with eosinophil infiltration. Epithelioid granulomas were observed around the area of necrosis (arrowheads) [hematoxylin-eosin, original ⫻ 100]. Top right, B: Vasculitis with eosinophil infiltration (arrows) [hematoxylin-eosin, original ⫻ 400]. Bottom left, C: Corresponding elastica van Gieson stain of top right, B shows partial destruction of vessel wall (arrows) [original ⫻ 400]. Bottom right, D: Clusters of Gram-positive, coryneform rods in the alveolar spaces (arrow) [Gram stain, original ⫻ 1,000]. 1238 Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 Selected Reports like lung inflammation in this case was induced by C ulcerans infection. Interestingly, bronchiectasis was observed on chest image. We assume that this has been newly caused by C ulcerans infection, not been predisposed to the infection, because this has been gradually improved with antibiotics and reversible. C ulcerans infection in human occurs after consuming unpasteurized milk or coming in contact with dairy animals. Person-to-person transmission of C ulcerans is rare.7 Our patient had no direct contact with dairy livestock, or unpasteurized dairy products, and no person around the patient complained same symptoms. Recently, C ulcerans producing diphtheria toxin was isolated from nasal discharge of domestic cats in the United Kingdom, and the isolates were found to exhibit the predominant ribotypes observed among human clinical isolates.7 Hatanaka et al8 reported a case of diphtheria-like illness in a Japanese woman who had been scratched by a cat with a runny nose. Our patient kept 12 cats in his home, with several of them exhibiting rhinorrhea and sneezing prior to onset of his illness. These cats might have been carriers of C ulcerans and possibly transmitted the bacterium to him. We report the first case of C ulcerans infection of the lung mimicking CSS. This bacterium should be taken into consideration when encountering the histologic features of CSS in the lung, and effective antimicrobial chemotherapy should be planned accordingly. ACKNOWLEDGMENT: The authors are grateful to Dr. Masanori Kitaichi, Kinki-chuo Chest Medical Center, for his comments on histopathology, and to Dr. Takako Komiya, Dr. Masaaki Iwaki, Dr. Motohide Takahashi, and Dr. Yoshichika Arakawa, National Institute of Infectious Disease, for their help in the identification of C ulcerans. Thanks are also due to Dr. Takuya Ueno, Ms. Mariko Ono, and Ms. Kaori Hirano for their technical assistance. References 1 Gubler JG, Wust J, Krech T, et al. Classical pseudomembranous diphtheria caused by Corynebacterium ulcerans. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1990; 120:1812–1816 2 Siegel SM, Haile CA. Corynebacterium ulcerans pneumonia [letter]. South Med J 1985; 78:1267 3 Dessau RB, Brandt-Christensen M, Jensen OJ, et al. Pulmonary nodules due to Corynebacterium ulcerans. Eur Respir J 1995; 8:651– 653 4 Reinhardt DJ, Lee A, Popovic T. Antitoxin-in-membrane and antitoxin-in well assays for detection of toxigenic Corynebacterium ulcerans. J Clin Microbiol 1998; 36:207–210 5 Miyamura K, Nishio S, Ito A, et al. Micro cell culture method for detection of diphtheria toxin and antitoxin titers by VERO cells. J Biol Stand 1974; 2:189 –201 6 North I, Strek ME, Leff AR. Churg-Strauss syndrome. Lancet 2003; 361:587–594 7 De Zoysa A, Hawkey PM, Engler K, et al. Characterization of toxigenic Corynebacterium ulcerans strains isolated from humans and domestic cats in the United Kingdom. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:4377– 4381 8 Hatanaka A, Tsunoda A, Okamoto M, et al. Corynebacterium ulcerans diphtheria in Japan. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9:752– 753 www.chestjournal.org Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 Adenocarcinoma of the Lung Presenting as a Mycetoma With an Air Crescent Sign* Lan-Fu Wang, MD; Hsi Chu, MD; Yuh-Min Chen, MD, PhD, FCCP; and Reury-Perng Perng, MD, PhD, FCCP An 89-year-old man was admitted to the hospital due to intermittent anterior chest wall pain for > 1 month. A chest radiograph obtained on November 9, 2004, demonstrated a mass with an irregular border, inside a thinwalled cavity, located in the superior segment of the left lower lobe. A chest CT scan revealed an irregular thinwalled cavity, 5.9 ⴛ 5.4 ⴛ 4 cm in size, with an aircrescent sign in the superior segment of the left lower lobe, and an intracavitary fungus ball-like mass. A bronchoscopic examination was performed, revealing only external compression of the left lower lobe bronchial lumen. Cultures from both the brushing cytology and brushing fungus specimens were negative. Since the patient was a heavy smoker and the chest radiograph obtained 23 months before had revealed no active pulmonary lesion, neoplastic growth was still highly suspected. Thus, an 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography study was performed on November 25, and a mass with a slightly increased standard uptake value (3.17; cutoff value, 2.5) was found. He received a left lower lobe lobectomy on December 23, and a tumor with many septum-like structures connecting the surrounding pulmonary parenchymal tissue was found in the superior segment of the left lower lobe. The final pathologic diagnosis was adenocarcinoma of the lung (pT2N0M0). Thus, even though the chest radiograph and chest CT scan showed a typical air-crescent sign (ie, mass inside a cavity) favoring a mycetoma, the physician should still keep in mind that lung cancer may also unusually present in this way. (CHEST 2007; 131:1239 –1242) Key words: air crescent sign; lung cancer; mycetoma Abbreviations: FDG ⫽ 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose; PET ⫽ positron emission tomography; SUV ⫽ standard uptake value; TB ⫽ tuberculosis *From the Chest Department, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China. The authors have reported to the ACCP that no significant conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article. Manuscript received June 21, 2006; revision accepted August 2, 2006. Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal. org/misc/reprints.shtml). Correspondence to: Yuh-Min Chen, MD, PhD, FCCP, Chest Department, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, 201 Section 2, Shih-Pai Rd, Taipei 112, Taiwan, Republic of China; e-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.1378/chest.06-1551 CHEST / 131 / 4 / APRIL, 2007 1239 n 89-year-old man was admitted to the hospital on A November 9, 2004, due to intermittent anterior chest wall pain for ⬎ 1 month. No fever, cough, or body weight loss was noted. His medical history included ischemic heart disease, which was under regular medical control. He had smoked 10 cigarettes daily for ⬎ 40 years. A physical examination revealed no remarkable findings. The chest radiograph obtained on hospital admission revealed a thin-walled cavity and a mass with an irregular border inside the cavity, which was located in the superior segment of the left lower lobe. A chest CT scan revealed a thin-walled cavity with irregular outer border, 5.9 ⫻ 5.4 ⫻ 4 cm in size, with an air-crescent sign, in the superior segment of the left lower lobe, and an intracavitary fungus ball-like mass (Fig 1). The thickness of this thin, wall-like structure was approximately 2 to 5 mm, with a less clear outside border infiltrating into the pulmonary parenchyma. Bronchoscopic examination disclosed a narrowing of the left lower lobe bronchial lumen, caused by external compression. Brushing cytology, acid-fast bacilli smear and culture, and fungus culture showed negative results. Since the patient was a smoker and the chest radiograph obtained in December 2003 had shown no active pulmonary lesion, pulmonary neoplastic growth was still highly suspected. Thus, an 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scan was arranged, and the resulting images showed a homogenous mass 6.1 ⫻ 6 ⫻ 6.1 cm in the left lower lobe (Fig 2). The standard uptake value (SUV) of the FDG uptake was 3.17 for this mass. Since a mycetoma would not be expected to have any uptake on PET scanning, because it does not have a blood supply, any uptake at all within the central solid lesion would rule out the presence of a mycetoma. Thus, the PET scan results excluded the possibility of mycetoma in our patient. He then underwent a left lower lobe lobectomy. The operative findings were a mass with many septum-like structures connecting the surrounding pulmonary parenchymal tissue in the superior segment of the left lower lobe (Fig 3), and the final pathologic diagnosis was adenocarcinoma of the lung (pT2N0M0) [Fig 4]. Discussion Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the world. The common radiologic presentations of lung cancer Figure 1. Chest CT scan shows one 5.9 ⫻ 5.4 ⫻ 4 cm cavitary lesion with an irregular thin wall, and one 4.6 ⫻ 3.1 ⫻ 3 cm lobulated mass in the center (with an air-crescent sign), in the superior segment of the left lower lobe. Top, A: coronal section of the three-dimensional reconstruction. Bottom, B: cross section of the lung window view. The thickness of this irregular wall was about 2 to 5 mm, with a less clear outside border infiltrating into the pulmonary parenchyma. 1240 Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 Figure 2. FDG-PET scan shows an obvious and homogeneous mass with an SUV of 3.17, located over the left lower lobe (arrow). Selected Reports Figure 3. A gray-white firm tumor, 4.2 ⫻ 3.5 ⫻ 2.2 cm in size, with some septum-like structures in the peripheral region, was noted inside the left lower lobe (17 ⫻ 7.2 ⫻ 4.8 cm). patients include a solitary pulmonary nodule, lung consolidation, collapse, pleural effusion, and/or mediastinal widening. Lung cancer presenting with an aircrescent sign or as a mycetoma-like lesion is very rare. This air-crescent sign seen (ball-in-hole) in the chest radiograph or chest CT scan is most often associated with an inflammatory process such as mycetoma, a hydatid cyst, lung abscess, or pulmonary tuberculosis (TB).1 Mycetoma frequently occurs in preexisting cavitary lesions of the lung formed by a previous pulmonary tuberculous infection. In addition to combining with Figure 4. Microscopic finding of sections of the left lower lobe tumor shows well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with a papillary growth pattern (hematoxylin-eosin, original ⫻100). www.chestjournal.org Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 mycetoma, pulmonary TB can also be found together with lung cancer, simultaneously or sequentially.2 However, in our previous large-scale retrospective analysis2 of 31 patients with pulmonary TB and lung cancer from 1988 to 1994, including 3,928 lung cancer patient profiles, we never found a cavitary TB lesion with mycetoma inside the cavity, combined with another lung cancer lesion, in the same patient. Mycetoma was more frequently suspected or misdiagnosed as lung cancer,3 and only rarely did mycetoma arise from a cavitary lesion within lung cancer.4 Although lung cancer can occur after previous pulmonary injury, such as a scar cancer growing from a fibrotic or granuloma lesion due to previous pulmonary TB infection, the majority of lung cancers are due to smoking. Even in those lung cancers that derive from previous pulmonary injury, the majority of lesions are located at or derived from a fibrotic or granuloma lesion, instead of a TB cavity. When lung cancer does occur in a previously existing cavity, one will find, in addition to typical fibronodular lesions distributed in the lung, an irregular nodular lesion, which progressively enlarges, inside a chronic preexisting TB cavity. In contrast, no evidence of any pulmonary TB lesions was found in the image study of our case; thus, pulmonary TB with a TB cavity and tumor growth inside the cavity was much less likely to have been our clinical impression before the patient received surgical intervention. The reason why our patient had a ball-in-hole or an air-crescent sign appearance in the chest image was that the tumor infiltrated with a paracicatrical effect around the peripheral pulmonary parenchyma, thus inducing compensatory emphysematous or cystic change between the tumor-infiltrating bands. This was documented by both the surgical gross specimens and pathologic findings. In addition, in patients with a pulmonary mycetoma (fungal ball), the radiographic feature is usually evident as an upper lobe cavitary lesion with an intracavitary mobile mass and an air-crescent sign on the periphery.5,6 A change in the position of the mycetoma occurring when the patient changes his position is a valuable radiologic sign for the diagnosis of mycetoma.5,7 Thus, the classic CT scan workup of a mycetoma would include both supine and prone scanning studies to demonstrate whether the central mass is free or attached to the cystic wall. The reason we performed a PET scan to rule out a malignancy is that the patient was a heavy smoker and his chest radiograph examination from 23 months before had negative findings, implying a greater possibility of cancer formation. PET scanning is a sensitive imaging method for both inflammatory processes and malignancies.8 Many inflammatory lesions have a maximal SUV of ⬍ 2.5, and the specificity of this cutoff SUV was approximately 70 to 90% in one study.9 In addition to the SUV data, PET imaging itself is another important differentiating clue, as a fungus ball will show a cavitary lesion with an increased SUV at the wall of the cavity, CHEST / 131 / 4 / APRIL, 2007 1241 with no radioactivity inside the cavity, since mycetoma does not have a blood supply. Thus, any uptake at all within the central solid lesion would rule out the presence of a mycetoma (Fig 5). Topologically, the hyphae are still outside the patient’s body, so the mycetoma is more of a colonization than an infection, similar to the microbes found on the skin surface; this also explains why there would be no uptake at all within the solid portion of a mycetoma, but only around the edges of the host cavity, as shown in Figure 5. Thus, a mycetoma will have increased uptake in the wall of the cavity on PET scans, but not in the fungal ball. In contrast, in patients with lung cancer a mass with increased SUV (Fig 2) is revealed. In patients with lung cancer, PET scanning is usually incorporated into the conventional staging algorithms for a patient with nonsmall cell lung cancer10 and is also able to evaluate the primary lesion.9 In conclusion, the physician should keep in mind that lung cancer may have an air-crescent sign or mycetomalike appearance in the roentgenographic images. In addition to clinical history and chest imaging studies obtained with the patient in both the supine and prone positions, PET scan images can help in the differential diagnosis. References 1 Abramson S. The air crescent sign. Radiology 2001; 218:230 – 232 2 Chen YM, Lee PY, Chao JY, et al. Shortened survival of lung cancer patients with active pulmonary tuberculous infection. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1996; 26:322–327 3 Torpoco JO, Yousuffuddin M, Pate JW. Aspergilloma within a malignant pulmonary cavity. Chest 1976; 69:561–563 4 Osinowo O, Softah AL, Zahrani K, et al. Pulmonary aspergilloma simulating bronchogenic carcinoma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2003; 45:59 – 62 5 Shuji B, Jiro F, Yoko F, et al. Cavitary lung cancer with an aspergilloma-like shadow. Lung Cancer 1999; 26:195–198 6 Ayman OS, Pranatharthi HC. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Chest 2002; 121:1988 –1999 7 Roberts CM, Citron KM, Strickland B. Intrathoracic aspergilloma: role of CT in diagnosis and treatment. Radiology 1987; 165:123–128 8 Reichenberger F, Habicht JM, Gratwohl A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in neutropenic patients. Eur Respir J 2002; 19:743–755 9 Ho CL. Clinical PET imaging: an Asian perspective. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2004; 33:155–165 10 Victor K, Rodney JH, Michael PM, et al. Clinical impact of F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:111–118 Hemoglobin Bassett Produces Low Pulse Oximeter and Cooximeter Readings* Arvind Das, MD; Sameer Sinha; and James D. Hoyer, MD Figure 5. Chest CT scan (top, A) and PET scan image (bottom, B) of a 74-year-old man with a pulmonary mycetoma of the right upper lobe. The CT scan (top, A) shows a mass inside a thin-walled cavity located in the right upper lobe (arrow). A PET scan (bottom, B) from November 16, 2000, shows a mass in the lung with an absence of radioactivity in the central portion and a slightly increased FDG uptake (SUV, 1.63 vs 0.45 in a contralateral normal lung) at the periphery of the lesion, which is compatible with mycetoma of the lung rather than a malignancy (arrow). 1242 Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 Variant hemoglobins can have altered oxygen affinity and can produce changes in oximeter readings. We present a case of hemoglobin Bassett, a possible cause of low pulse oximeter and co-oximeter readings in a 63-year-old woman. (CHEST 2007; 131:1242–1244) Key words: hemoglobin Bassett; pulse oximetry; variant hemoglobin Abbreviations: P50 ⫽ partial pressure of oxygen required for 50% saturation of hemoglobin; Spo2 ⫽ oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry Selected Reports Case Report woman went for an elective hernia repair that A 63-year-old cancelled due to low oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry (Spo2) readings. Her only relevant symptom was mild dyspnea on exertion. She had a history of acute pancreatitis 15 years earlier. During much of that period, she had been on a respirator, and had difficulty weaning from it despite a tracheostomy. Once off the respirator, she had gradually improved to the point of normality, and the tracheostomy stoma closed spontaneously. She had 15-pack-year smoking history, and she quit smoking 20 years ago. No one else in her family had any blood or respiratory disorders. The patient was moderately obese, had normal vital signs, and had a normal physical examination except for the inguinal hernia and mild bilateral lymphedema of legs, but Spo2 was 85% at rest. Pulmonary function tests showed a mild restrictive pattern with a borderline normal diffusing capacity, and chest radiographic findings were normal. The serum metabolic panel was normal, including the levels of phosphorus and thyroid-stimulating hormone. The CBC was normal, with a hemoglobin level of 14.4 g/dL. A simple pulmonary stress test was performed on a stationary bike. The patient stopped exercising 6 min into the test (at 75 W) due to general fatigue, without dyspnea. Her Spo2 dropped to 81% within the first minute of exercise and remained at this level throughout the exercise. After 3 min of rest, her Spo2 increased back to 85%. She did not have exercise-induced bronchospasm, or ECG changes. Arterial blood gas measurement (ABL 700 series; Radiometer; Copenhagen, Denmark) showed a pH 7.42; Paco2, 31 mm Hg; Pao2, 85mm Hg; and arterial oxygen saturation of 86% at rest on room air. Co-oximetry showed no methemoglobinemia, and both fetal and carboxy hemoglobin levels of ⬍ 1%. Hemoglobin analysis was performed at Mayo Clinic utilizing alkaline and acid electrophoresis, isoelectric focusing, globin chain electrophoresis, and cation-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography. These methods identified a hemoglobin variant that accounted for 16.1% of the total hemoglobin. The electrophoretic characteristics were consistent with hemoglobin Bassett, and DNA sequencing of the ␣-globin genes confirmed a GAC to GCC (Asp to Ala) substitution at position 94. Using a sample of the patients’ whole blood in the Hemox Analyzer (TCS Scientific Corporation; Southampton, PA), a hemoglobin-oxygen equilibrium curve was plotted that was normal, with a partial pressure of oxygen required for 50% saturation of the hemoglobin (P50) of 28 mm Hg (Fig 1). *From the Department of Medicine (Dr. Das), UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ; University of Connecticut (Mr. Sinha), Storrs, CT; and Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology (Dr. Hoyer), Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Manuscript received June 13, 2006; revision accepted September 6, 2006. Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal. org/misc/reprints.shtml). Correspondence to: Arvind Das, MD, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, 81 Veronica Ave, Suite 201, Somerset, NJ 08873; e-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.1378/chest.06-1310 www.chestjournal.org Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 Figure 1. Cation-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography for hemoglobin Bassett. The abnormal hemoglobin elutes as a distinct peak at 4.62 min. Discussion Low Spo2 is generally due to a low Pao2. However, low Spo2 can also be caused by mechanical and other biological factors (Table 1). Once these causes have been excluded, a rightward shifted hemoglobin-oxygen equilibrium curve, as reflected by a higher P50, becomes the most plausible explanation. Causes of a right-shifted hemoglobin-oxygen curve include hypercapnea, chronic acidosis, hypophosphatemia, hypothyroidism, infusion of stored blood, reduced levels of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate, fever, and certain variant hemoglobins. Hemoglobin Bassett is known to have a substitution of Asp3Ala at position 94 of the ␣1 globin chain. This happens to be a ␣12 contact region and is crucial for the normal oxygenation and deoxygenating of the hemoglobin. But ␣1 globin forms only 30% of the total hemoglobin in humans. Therefore, a mutation in just one of the ␣1 globin genes would alter only Table 1—Causes of Falsely Low SpO2 Readings Hypoperfusion of the probe site from hypotension, cold, fear, and medications Dark skin pigmentation, painted nails, and tissue edema at the probe site IV dyes Methylene blue in blood Body movement Pulsatile venous system, eg, during cardiopulmonary resuscitation and from tricuspid regurgitation Interference from radiated bright light, including fluorescent and infrared lights Methemoglobinemia M hemoglobins CHEST / 131 / 4 / APRIL, 2007 1243 15% of the total hemoglobin. We believe this to be the case in our subject, in whom hemoglobin Bassett constituted only 16.1% of the total hemoglobin, and therefore had no significant effect on the overall P50. The clinical manifestations of variant hemoglobins can vary from a complete lack of symptoms to mild anemia, polycythemia, dyspnea, to respiratory distress and cyanosis starting in early life.1–4 Supplemental oxygen can be utilized to maximize the Pao2, hence the arterial oxygen saturation and the oxygencarrying capacity of the subject’s blood. Additional benefit can be obtained by optimizing the subject’s hemoglobin level, and by transfusion of normal blood. 1244 Downloaded From: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ on 10/28/2014 References 1 Edmonds L, Fairbanks VF, McCormick DJ, et al. Hemoglobin Bassett, alpha 94 (G1) Asp-Ala: a new low O2-affinity variant associated with chronic anemia [abstract]. Blood, Abstract issue for American Society Hematology, 1998; 97 2 Middleton PM, Henry JA. Pulse oximetry: evolution and directions. Int J Clin Pract 2000; 54:438 – 444 3 Sinex JE. Pulse oximetry: principles and limitations. Am J Emerg Med 1999; 17:59 – 66 4 Abdulmalik O, Safo M, Lerner N, et al. Characterization of hemoglobin Bassett (␣94Asp3 Ala), a variant with very low oxygen affinity. Am J Hematol 2004; 77:268 –276 Selected Reports

© Copyright 2026