The Court System

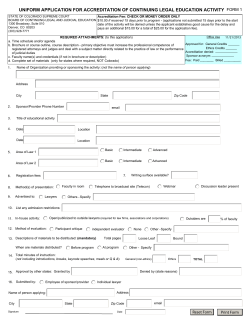

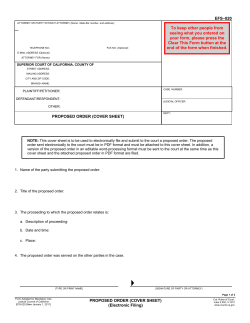

The Court System Aim of lecture: Understand Chapter III of the Commonwealth Constitution and: (a) The separation of powers doctrine (b) The meaning of ‘judicial power’ Understand the courts and separation of powers at a state level and: (a) Totani (b) Kable Lecture Overview: COURTS FEDERAL STATE Separation of powers Cth Constitution Boilermakers etc NSW Constitution Totani/Kable etc What is a court? ‘At the end of the day it has unfortunately to be said that there emerges no sure guide, no unmistakable hall mark by which a ‘court’ may unerringly be identified. It is largely a matter of impression.’ Lord Edmund in Attorney-General v British Broadcasting Corporation [1981] AC 303 at 351 Why is this important? 1. Bodies which look like courts but are not courts (ie: tribunals) 2. Bodies may be found to be constitutionally invalid (eg: ‘new’ Australian Military Court declared invalid in 2009) 3. Processes may ‘look’ judicial but are not (eg: Manus Island in 2014) The Court System What is it that ‘makes a court’ – judicial power The way in which the exercise of judicial power is separated from legislative and executive power – or the Separation of Powers The differences between Federal and State judicial power The attempts made to overcome differences between the Federal and State judicial powers – or the cross vesting scheme. Jurisdiction and Heirarchy of courts (IMPORTANT!) Judicial hierarchies Commonwealth courts Must be a Chapter III court: ‘judicial power’ Judicial power s71 Constitution: “The judicial power of the Commonwealth shall be vested in a Federal Supreme Court, to be called the High Court of Australia, and in such other federal courts as the Parliament creates, and in such other courts as it invests with federal jurisdiction. The High Court shall consist of a Chief Justice, and so many other Justices, not less than two, as the Parliament prescribes.” S71 Constitution: Vests the judicial power of the Commonwealth in the High Court and other Chapter III Courts. Acknowledges that the Federal Parliament can invest State courts with Federal jurisdiction – (mentioned in s77(iii) of the Constitution) – and provides foundation for cross vesting scheme. Makes clear that the judicial power of the Commonwealth can only be exercised by these s71 courts – or that the judicial power is clearly separated from the legislative and executive powers. What is ‘judicial power’? Answer in Chapter III of Commonwealth Constitution AND Constitutional case law decided by High Court (eg: Boilermaker’s Case) Huddart, Parker & Co Pty Ltd v Moorehead (1909) 8 CLR 330 at 357 per Griffiths CJ: “I am of opinion that the words ‘judicial power’ as used in sec 71 of the Constitution mean the power which every sovereign authority must of necessity have to decide controversies between its subjects, or between itself and its subjects, whether the rights relate to life, liberty or property. The exercise of this power does not begin until some tribunal which has power to give a binding and authoritative decision (whether subject to appeal or not) is called upon to take action.” R v Trade Practices Tribunal; Ex parte Tasmanian Breweries Pty Ltd 1970] HCA 8; (1970) 123 CLR 361 [J]udicial power involves, as a general rule, a decision settling for the future, as between defined persons or classes of persons, a question as to the existence of a right or obligation, so that an exercise of the power creates a new charter by reference to which that question is in future to be decided as between those persons or classes of persons. In other words, the process to be followed must generally be an inquiry concerning the law as it is and the facts as they are, followed by an application of the law as determined to the facts as determined; and the end to be reached must be an act which, so long as it stands, entitles and obliges the persons between whom it intervenes, to observance of the rights and obligations that the application of law to facts has shown to exist. Judicial power of the Commonwealth s73: a “judgement, decree, order or sentence” e.g. Saffron v The Queen (1953) 88 CLR 523 or ss75-77 a “matter” e.g. In re Judiciary and Navigation Acts 29 CLR 257 (1921) Alexander’s case Waterside Workers Federation v J W Alexander Ltd (1918) 25 CLR 434 Difference between judicial and nonjudicial power s72 Commonwealth Constitution: judges appointed for life (now until retirement age of 70) Griffith CJ… As soon as man emerged from the savage state and formed settled communities, the necessity became apparent of rules to regulate conduct. It also became necessary to make provision for their enforcement, and for the settlement of private controversies between individuals. In each case the right to do so was assumed by the community at large, and vested in some person or authority representing that community. Hence arose lawgivers and Judges. And as civilization advanced, and persons came to discriminate between the diverse functions of the community, these functions were called "the judicial power" as distinguished from the legislative and executive powers. (at 434) Barton J at 451: judicial power “It is the power of a Court to decide and pronounce a judgement and carry it into effect between persons and parties who bring a case before it for decision….” “From the earliest times, when people have associated themselves into settled communities, their interest has dictated to them the adoption of rules of conduct as the alternative to anarchy and as the only means of securing internal peace in the pursuit of their avocations. The making of such rules, by whatever term it may have been known, is the making of laws; that is, it is legislation. But laws of themselves were of little force without bodies which could enforce them- and authorities with power to enforce them were created. These authorities might or might not be called Judges, the tribunals might not be called Courts, and the power which they exercised might or might not be called judicial power. Whether persons were Judges, whether tribunals were Courts, and whether they exercised what is now called judicial power, depended and depends on substance and not on mere name. Enforceable decision by an authority constituted by law at the suit of a party submitting a case to it for decision is in character a judicial function.” Barton J 451 Powers J at 485 “a Court of judicature is a Court to settle existing rights between parties, but a compulsory arbitration Court is not a Court to settle existing rights. Its powers are more legislative than judicial. It is empowered to fix by an award, which is to have the effect of law, what wages are to be paid … The award is binding as a declaration of the law on persons who have not had any existing rights prior to the award, for it compels employers to pay the minimum wage fixed by the award …. The Arbitration Court is only asked to make an award when employers or employees are not content with existing rights and would not be content with any declaration as to existing rights.” Isaacs and Rich JJ at 463-4 “Both [the judicial and arbitral power] presuppose a dispute, and a hearing or investigation, and a decision. But the essential difference is that the judicial power is concerned with the ascertainment, declaration and enforcement of the rights and liabilities of the parties as they exist, or are deemed to exist, at the moment the proceedings are instituted; whereas the function of arbitral power in relation to industrial disputes is to ascertain and declare, but not enforce, what in the opinion of the arbitrator ought to be the respective rights and liabilities of the parties in relation to each other”. R v Davison (1954) 90 CLR 353 at 369 “The truth is that the ascertainment of existing rights by the judicial determination of issues of fact or law falls exclusively within judicial power so that the Parliament cannot confide the function to any person or body but a court constituted under ss71 and 72 of the Constitution.” Separation of Powers The reality? The legislature (Cth) The Judiciary (High Court) Executive (Governor-General) His Excellency the Honourable Peter Cosgrove AK MC (Retd) Sir Gerard Brennan: “The Courts are an important element in the system of checks and balances that preserves our societies from a concentration of official power that might otherwise oppress the people and restrict their freedom under the law. The Courts are an organ of Government but they are not part of the Executive Government of that country. … But the apolitical organ of government, the Courts, are there continually to extend the protection of the law equally to all who are subject to their jurisdiction: to the minority as well as the majority, the disadvantaged as well as the powerful, to the sinners as well as the saints, to the politically incorrect as well as those who embrace a contemporary orthodoxy. The principle of judicial independence is not proclaimed in order to benefit the Judges; it is proclaimed in order to guarantee a fair and impartial hearing and an unswerving obedience to the rule of law. That is the way in which our peoples secure their freedom under the law.” The reality? 2 limbs….. Separation of judicial powers principles: Limb 1: Commonwealth judicial power can only be exercised by courts referred to in section 71 (Alexander’s case) Limb 2: courts exercising Commonwealth judicial power can only exercise judicial power and non-judicial power that is incidental to the exercise of judicial power (Boilermakers’ case) Boilermakers case R v Kirby; ex parte Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956) 94 CLR 254 High Court (at 267) “in a federal form of government a part is necessarily assigned to the judicature which places it in a position unknown in a unitary system or under a flexible constitution where Parliament is supreme…The conception of independent governments existing in the one area and exercising powers in different fields of action carefully defined by law could not be carried into practical effect unless the ultimate responsibility of deciding upon the limits of respective powers of the governments were placed in the federal judicature. Separation of judicial power “Chapter III does not allow the exercise of a jurisdiction which of its very nature belongs to the judicial power of the Commonwealth by a body established for purposes foreign to the judicial power, notwithstanding that it is organized as a court and in a manner which might otherwise satisfy ss71 and 72, and that Chap III does not allow a combination with judicial power of functions which are not ancillary or incidental to its exercise but are foreign to it” (at 296) Wilson v Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs (1996) 189 CLR 1 “the separation of functions is designed to provide checks and balances on the exercise of power by the respective organs of government in which powers are reposed.” per Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey, McHugh and Gummow JJ at 11 Persona Designata rule Hilton v Wells (1985) 157CLR 57 “Although the Parliament cannot confer non –judicial powers on a federal court, or invest a State court with a non-judicial power, there is no necessary constitutional impediment which prevents it from conferring non-judicial power on a particular individual who happens to be a member of a court” (at 68 Per Gibbs CJ, Wilson and Dawson JJ.) Delegation of Federal Judicial Power Harris v Caladine (1991) 172 CLR 84 Power can be delegated but: the delegation cannot be such that the judges no longer manage the more important aspects of contested matters, and the exercise of the delegated power must be subject to review by the judges themselves. The reality? NSW separation of powers New South Wales Constitution does not enshrine a separation of powers: Building Construction Employees and Builders' Labourers' Federation of New South Wales v Minister for Industrial Relations & Anor (1986) 7 NSWLR 372; SEE: Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW) (1996) 189 CLR 51 Queensland laws http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/queensl and/attorneygeneral-jarrod-bleijie-quieton-potential-bikie-law-changes-2014012131707.html Yandina Five – 5th July 2014 “Yandina Five wait on High Court ruling against bikie laws” in Sunshine Coast Daily Totani and future challenges Attorney-General Jarrod Bleijie can not say if the government will re-write its anti-association and criminal gang laws, if the legislation is struck down by the High Court. With at least two High Court challenges to its criminal gang legislation in the works – one unionled and the other spearheaded by the United Motorcycle Council of Queensland – Mr Bleijie would not be drawn into “hypothetical” situations about what the government would do if it lost. January 22nd 2014 Read more: http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/queensland/attorneygeneraljarrod-bleijie-quiet-on-potential-bikie-law-changes-2014012131707.html#ixzz2r4kC0yAP Under s 10(1) of the SOCC Act, the Attorney-General is, on the making of an application by the Commissioner of Police, empowered to “make a declaration” if satisfied of two criteria: “(a) members of the organisation associate for the purpose of organising, planning, facilitating, supporting or engaging in serious criminal activity; and (b) the organisation represents a risk to public safety and order in this State”. Section 14(1) provided that the Court “must” make a control order “if the Court is satisfied that the defendant is a member of a declared organisation”. a breach of either of these or any additional conditions of a control order is an offence punishable by five years imprisonment. Justice French ….the extent of the intrusions upon personal freedom effected by a control order is relevant to the characterisation of the duty imposed upon the Magistrates Court under s 14(1) of the Act and to whether, contrary to assumptions reflected in Ch III of the Constitution, s 14(1) removes or impairs that independence from the executive that is a defining characteristic of courts of law in Australia. Cross Vesting Scheme s77(iii) Constitution s39(2) Judiciary Act “The several Courts of the States shall within the limits of their several jurisdictions, whether such limits are as to locality, subject-matter or otherwise, be invested with federal jurisdiction, in all matters in which the High Court has original jurisdiction or in which original jurisdiction can be conferred on it.” Issues with Cross Vesting Re Wakim; ex parte McNally (1999) 163 ALR 270 Commonwealth or Ch III Courts High Court of Australia Federal Court of Australia Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) Family Court of Australia Constitution ss71-77 Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) Federal Magistrates Court of Australia Federal Magistrates Court Act 1999 (Cth) NSW Courts Supreme Court of New South Wales District Court of New South Wales Supreme Court Act 1970 (NSW) District Court Act 1973 (NSW) Local Courts Local Courts (Civil Claims) Act 1970 (NSW) Non-judicial tribunals Administrative Appeals Tribunal Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Australian Competition Tribunal Australian Industrial Relations Commission Australian Securities Commission Copyright Tribunal Refugee Review Tribunal Registrar of Trade Marks The Commissioner of Taxation

© Copyright 2026