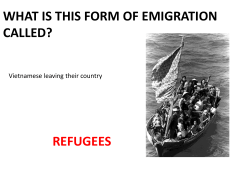

A World Divided Western Kingdoms, Byzantium, and the Islamic World, ca. 376-1000

A World Divided Western Kingdoms, Byzantium, and the Islamic World, ca. 376-1000 1 A World Divided The Big Picture Ostrogothic Kingdom Visigothic Kingdom 450 Umayyad Dynasty Merovingian Dynasty 750 Carolingian Dynasty ’Abbasid Dynasty 950 2 A World Divided Political Disintegration of the Roman Empire – Sixth Century: By the 500s, the Roman Empire could no longer be counted on to protect people within carefully guided borders. It had ceased to exist as a political and military entity. – In the West: In the Western portion of the old empire, Germanic invaders set up new kingdoms and converted to Christianity. The popes in Rome increasingly wielded greater authority. – In the East: In the eastern portion, the Byzantine Empire asserted control, making Greek rather than Latin the language of government. The Byzantines also reached out more to the Slavs on their northeast frontier, rather than the Germanic peoples to the northwest, bringing the Slavs into their sphere of influence. Further east, a new prophet arose out of Arabia. 3 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Life in a Germanic Clan and Family – Who were the Germani?: Who were the people who invaded the Italian peninsula and became dominant in western Europe? What were their cultures and societies like? 4 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Life in a Germanic Clan and Family – Indo-Europeans from Scandinavia: Around 500 B.C.E., these tribes began to migrate from Scandinavia into the regions around the Baltic Sea and into what is now Germany. – Evolving Groups: As the Germanic tribes fanned out and settled, they began to develop subtle differences, forming different groups: the Visigoths (western Goths), Ostrogoths (eastern Goths), Franks, Burgundians, Saxons, etc. – Clans: Since they all came from a relatively small area of Scandinavia, they shared many similar traits, most notably a clan-based structure in the areas of settlement. Kinship groups could be as big as 100,000 people, with 20,000 warriors. – No Written Record: The Germanic tribes had no written language of their own, so scholars have to rely on Roman accounts of this people, as well as 5 what can be figured out from archaeological digs. The Making of the Western Kingdoms A Gothic mummy, having been preserved in a peat bog Photo credit: Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen, Schloss Gottorf, Archaologisches Landesmuseum 6 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Life in a Germanic Clan and Family – Marriage: Men and women had clearly defined roles, with men taking care of cattle and most agricultural production, with women maintaining the household and doing some agricultural labor. Wives shared in their husband’s property. The Roman historian Tacitus described them as devoted husbands and wives. – Polygyny: Scarce records suggest that pre-Christian German men practiced polygyny, as many wives and more children would increase their influence within the kinship network. – Women’s Position: As healers of the sick and keepers of medicinal knowledge, women were often ascribed with the powers of prophecy. Female elders were influential in the clan structure. 7 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Life in a Germanic Clan and Family – Adultery: Cases of adultery were treated harshly as they threatened the kinship structure, such as a mummy of a fifteen-year-old girl who was drowned, having been blindfolded and shaven bald. – Clothing: German people dressed very differently than Romans. Men wore trousers, long-sleeved jackets, and a flowing cape, as well as elaborately designed jewelry of gold and silver. Women wore ankle-length dresses colored with vegetable dyes, as well as jewelry depending on their social status. – Diet and Agriculture: The German people raised cattle but seldom ate meet as the animals’ milk was too valuable. They invented a heavy plow pulled by an oxen team that could turn over the hard clay soil of northern Europe. But they often could not grow enough grain for their needs since the growing season was short, and wars frequently brought famine. Women only grew to just under 5 feet, while men on average stood 5’6”. 8 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Heroic Society – Warrior Culture: Like the ancient Greeks, warfare and heroism played a large role in Germanic culture, and the Roman observers noted their constant belligerence. – Epic Poetry: Germanic poets composed oral epics much like the Greeks had, most famously the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf, which tells the story of a monster-killing hero, and provides a glimpse into Germanic warrior culture, where warriors would gather in halls to drink and boast of their feats. A trove of Anglo-Saxon treasures found in England from about 675 seem to back up the descriptions of Beowulf’s society. – Warrior Bands: Each clan had a chieftain who served as priest, main judge, and war leader, although he always consulted with the clans’ most elite warriors. Small bands of about 30 independent of a broader leadership would often carry out raids on neighbors, and the deeds of these groups seemed to be a source of much of the bragging. 9 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Infiltrating the Roman Empire, 376-476 – Increasing Cooperation: While fierce fighting perennially broke out on the Roman borders, Romans and Germans increasingly found opportunities to cooperate by the 300s. Ironically, many German warriors became mercenaries guarding the Roman border. – The Huns: In the late 300s, a Mongolian tribe known as the Huns came sweeping out of the central Asian steppes. The Huns were fearsome warriors even by German standards. Many Germans swept southward into the empire to find safer ground from the threat of the Huns, such as the Visigoths who sacked Rome in 410 B.C.E. 10 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Infiltrating the Roman Empire, 376-476 – Federate Treaties: The Romans could no longer pay for a massive army along its borders, so it started looking for cheaper alternatives. Federate treaties made tribes official allies. They would have permission to live within Roman borders if they agreed to fight Roman enemies when called upon. The Visigoths, for example, took up this deal to defend northern Italy against their traditional enemies, the Vandals. This led to the further blending of Germans and Romans. – Arian Christianity: Some federate tribes practiced paganism, but many practiced Arian Christianity, which had been outlawed by the mainstream church. Arius had believed that Jesus was not a full-fledged part of the Holy Trinity, not having a separate existence from God the Father. Arianism became a source of pride and identity for many Germans, leading to tensions with orthodox Christians. 11 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Infiltrating the Roman Empire, 376-476 Loss of Provinces – Great Britain: Around 407, the Romans recalled troops from Great Britain to come back and defend Italy. Christian Celtic Britons were left alone to defend themselves from invaders from Scandinavia and Scotland. – North Africa: The Vandals, who had invaded from the north and settled in North Africa, had become federates, but then broke away from Rome to create their own kingdom, with Carthage as their capital. 12 Germanic Invasions, Fifth Century 13 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Did Rome “Fall”? – Transformation: Most scholars argue that “transformation” is a more appropriate term than “fall,” which would mean a sudden, cataclysmic event. – Last Emperor Deposed: The military leader Odovacar deposed the last Western emperor in 476. It is unclear what Odovacar’s ethnicity was; he was mostly likely a Germanic leader from a tribe who had joined the Huns. He disdained the dual-emperor system, and symbolically shipped the imperial regalia off to Constantinople, and then appointed himself regent of Italy. 14 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Did Rome “Fall”? A Two-Way Transformation – Romans: The declining roman population had allowed plenty of room for the Germanic people to move in. Urban life decayed, as Germans preferred rural life. Wealthy Romans failed to pay taxes, Germans did not collect them, and the empire’s infrastructure began to fall into disrepair. Romans even switched from dressing in a toga to the trousers symbolic of rural life. – Germans: Germans were transformed by Roman influence, moving away from paganism and Arian Christianity to orthodox Christianity. In southern Europe, Germanic peoples began to speak Latin-influenced Romance languages instead of their native Gothic tongue. The blend created a whole new culture, which would become the Medieval West. 15 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Rise and Fall of a Frankish Dynasty – Christian Merovingians: In the late 400s, Germanic Franks in the former Roman province of Gaul consolidated the Merovingian Kingdom (named for a legendary ancestor, Merovech). – Clovis: The best remembered ruler of this dynasty was Clovis (r. 485511), who brutally murdered members of his own family to consolidate his rule. This tradition continued, with subsequent assassinations of Merovingian prince and princesses. – Conversion to Christianity: Unlike other Germanic leaders, Clovis converted to orthodox rather than Arian Christianity. Like Constantine, he promised to convert if he won a battle under the sign of the cross. This eventually led to closer ties between Germanic peoples and Roman Christianity. 16 The Making of the Western Kingdoms The Baptism of Clovis Figure 6.4 Photo credit: Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris 17 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Rise and Fall of a Frankish Dynasty – Fall of Merovingians: Subsequent Merovingian monarchs were not as competent as Clovis. Often children inherited the throne, died young, and leaving it to another child. Real power laid in the hands of the “mayors of the palace,” an office under the control of another noble family, the Carolingians. – Charles Martel and Pepin: This Carolingian leader won a great victory at Tours in 732 over invading Muslim forces. His son, Pepin the Short (r. 747-768), craved a royal title, so he courted Pope Zachary (r. 741-752) asking him to give legitimacy to his rule as king, thus forging a close bond between the Roman Church and future Frankish kings. 18 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Accomplishments and Destruction in Italy, ca. 490-750 – Theodoric and the Ostrogoths: Theodoric (r. 493-526), an Ostrogothic leader, overthrew Odovacar, the ruler who had deposed the last Roman Emperor. – Fostering Learning: Theodoric’s court was a center of learning and writing. Boethius, author of the The Consolations of Philosophy, was a high official in Theodoric’s court, although he was imprisoned for an accusation of treason, and wrote his famed work there. He was later executed. The monk Dionysus Exiguus calculated the date of the original Easter—Christ’s rising—and based the calendar which we still use on that date (he was slightly off—we know think Christ was born around 4 B.C.E.). – Historical Writing: Dionysus Exiguus’s pupil, Cassidorus (490-585) wrote the Origins of the Goths, claiming that the Goths had a rich history interwoven with and as significant as that of Rome. 19 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Accomplishments and Destruction in Italy, ca. 490-750 – Fall of Ostrogoths: Thoedoric’s daughter, Amalasuintha, succeeded him, but was murdered. Byzantine Emperor Justinian saw her death as an opportunity to retake Italy and reunite the Empire. – Lombards: Justinian had overburdened his resources, and his attempt to regain Italy failed at the hands of a fearsome Germanic people known as the Lombards, or “Long Beards.” In 568, they moved south into the Italian peninsula and conquered most of it. The Lombards were much less Romanized than the Ostrogoths. Pepin conquered their territory in northern Italy in the mid-eighth century – “Donation of Pepin”: When Pepin conquered northern Italy, the Byzantines asked for the land back. But he refused, and gave a piece of the territory to the pope in thanks for the support of his rule. This “donation” was the beginning of the Papal States, earthly territory directly controlled by the Pope. 20 The Making of the Western Kingdoms The Visigoths in Spain, 418-711 – Visigothic Weaknesses: The Visigoths, like the Ostrogoths, had ben Arian Christians, and had no connection to Rome. Their tendency toward political assassination greatly weakened their government. Visigoths also persecuted Jews living in their territory. They were eventually conquered by Muslims invading from North Africa around 711 C.E. – Islamic Iberia: Christian Iberians would spend the next 700 years trying to re-conquer the peninsula back from the Muslims. 21 The Making of the Western Kingdoms The Growing Power of the Popes – Power of the Church: As central authority fell away in Western Europe, people looked to bishops to do what secular officials had done. – Petrine Doctrine: Previous popes had based Rome’s central authority from the fact it was the capital of the Empire. But as the Empire fell away, they turned to the Petrine Doctrine. In the Gospel of Matthew, one passage has Christ saying that Peter, later the first Bishop of Rome, is the rock on which “I will build my church,” and that Peter is given the keys to heaven by Christ. The emperors in the east disagreed with this interpretation. – Pope Gregory the Great (r. 590-604): This pope did more to consolidate papal power than any other. He took over the day-to-day administration of Rome and used church revenue to feed the poor. He directed the defense of the city when the Lombards invaded. He settled disputes outside of Italy and extended his influence across Western Christiandom. 22 The Making of the Western Kingdoms Monasteries: Peaceful Havens in a Chaotic World – Benedict of Nursia (ca. 480 – 543): During his chaotic lifetime, many men and women sought refuge in monasteries or convents. This Italian founded an order of monks, and his sister, Scholastica, founded convents for women. He believed that individuals need guidance of a community, and eschewed fasting or flagellation. – Irish Christianity: A Romano-British Christian named Patrick (ca. 390-461) was captured and enslaved by Irish raiders. He believed that his mission was to convert pagan Ireland, and set up a series of monasteries to do so. – Conversion of Britain: Pope Gregory, a monk, was interested in converting the Anglo-Saxons of Britain. He sent monks to Britain in 597. Those monks encountered the ones in Ireland, who had developed a slightly different practice. In 664, this conflict was resolved when 23 both Irish and British monks agreed on the supremacy of rome. The Byzantine Empire Separation of the Byzantine Empire – Gradual Separation: Constantine planted the roots of the break, but it was a gradual process that happened over time. – Strong Defenses: After the sack of Rome in 410, Emperor Theodosius II built strong walls that kept the city safe during the turbulent 400s and for the next 1000 years. Those in the city watched from safety as Germanic tribes burned surrounding areas and the Huns invaded. 24 The Byzantine Empire Justinian and Theodora, r. 527-565 – Justinian’s Early Life: Born a peasant near Macedonia, Justinian’s path to become emperor because he was adopted by an uncle in the royal court, since the uncle recognized his talents. His uncle became emperor, and when he died in 527, Justinian became emperor. – Theodora: The most influential person in Justinian’s court was his wife, Theodora, who had humble origins, performing as an actress and dancer, capturing the emperor’s attention. – Nika Riot: Two political factions that supported different chariot racing teams broke out in a riot, allying themselves together to throw out Justinian. Theodora counseled Justinian to confront the rioters, and he put the revolt down brutally, killing as many as 30,000 and crushing any political opposition. 25 The Byzantine Empire Justinian and Theodora, r. 527-565 – Rebuilding the City: The city was devastated by the riot, and Justinian embarked on a rebuilding campaign that included a massive church, known as the Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom). – Legal Codification: Justinian also created an impressive legal code. Roman law had become immensely complicated and even contradictory since the time of the Republic’s Twelve Tables, so the emperor reorganized and clarified them. It survived in Europe in this form until about the thirteenth century. – Reconquering the West: Justinian tried to reconquer the Western territories of the Empire that had fallen to Germanic tribes, but his attempt eventually failed due to Roman resentment over more taxation and the eventual invasion of the Lombards. His rule over North Africa was more popular—he was preferred over the Arian Vandals—but his control did not last long there, either. 26 Justinian’s Conquests, 554 27 The Byzantine Empire Constantinople: The Vibrant City – Trading Hub: The city was made wealthy since it sat on the trade route with the Far East. Chinese silks and spices passed through, which brought a profit to those that resold these goods. – Lucrative Industries: The Byzantines also produced luxury items like expensive fabrics, glassware, and ivory pieces. The royal court held a monopoly on silk production. – Wealth Not Shared: Wealth was held by a small group of elites. The Byzantines abandoned the Roman practice of paying for the food of the poor, but there were some royal charity institutions. – Chariot Races: The great race track—called the hippodrome— could seat 40,000, and played a similar role to what the Colosseum had played in Rome. 28 The Byzantine Empire Military Might and Diplomatic Dealings – Provincial Organization: Constantinople itself, within its safe walls, was under civilian control, but the control of the provinces was give to military men. – The Army: The military was well paid, thoroughly armed, and highly professional. Archers shot from far distances, who were followed by the heavy cavalry, who were highly armored and could fight with lances, bows and arrows, and swords. The cavalry in turn was supported by an efficient infantry. The whole force was about 120,000 men at its height. Byzantium also had a strong navy, and a carefully guarded secret weapon: “Greek fire.” – Diplomacy: Byzantines often used bribes and tricks to get their ways with other states. Spies, lies, and money were used, as well as strategies to turn enemies against each other. 29 The Byzantine Empire Breaking Away from the West – Move to Greek: Justinian was the last emperor to use Latin as the language of governance. In 600s, the Byzantine bureaucracy changed to Greek. At the same time, Germanic peoples forgot how to speak and write Greek, leading to a cultural split. The Western Church started to use Latin exclusively (early Christian scriptures had been in Greek). – Question of Leadership: The question of who would lead the Church was driving the East and West apart. Byzantines Emperors: They were Caesaropapists, claiming that they led both church and state. Roman Popes: Claimed supreme leadership through the Petrine Doctrine. 30 The Byzantine Empire Breaking Away from the West – Icons: In the 400s ad 500s, the tradition of painting religious icons— images of Jesus, Mary, and the saints—became popular in the east. People believed these were windows to the divine that could bring divine help. – Iconoclasm: Byzantine emperor Leo III (r. 717-741) ruled all icons destroyed, in both east and west, since he equated the practice as worshipping idols, which is forbidden in the Old Testament. The sale of icons were also a major source of income for monasteries, which the emperor saw as too powerful. A flurry of iconoclasm (meaning “icon breaking”) occurred in the East. – Defiance in the West: Pope Gregory II (r. 715 – 731), defied Leo’s order to destroy icons, exacerbating tensions between Constantinople and Rome even further. 31 The Byzantine Empire Breaking Away from the West A Byzantine icon of the crucifixion painted between 9th – 13th century C.E. 32 The Byzantine Empire Orthodox Church – Moving toward Separation: The church grew further divided until it eventually became two separate churches: The Orthodox Church in the East and the Catholic Church in the West. – The Pentarchs: Church leaders in the East rejected the idea of the supremacy of the pope, and instead thought that the church should be led by the bishops, of the five chief cities: Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch. Known as the Pentarchs, they would meet to discuss matters of doctrine. – The Final Break: Decisions made by popes alone were rejected by the other Pentarchs. The pope and the patriarch of Constantinople excommunicated each other in 1054, creating a permanent break. 33 The Byzantine Empire Converting the Slavs, 560 - ca. 1000 The Slavs: Tribes of this people—Serbs, Croats, and Avars—began settling along the Danube River, what had been the northeast border of the Roman Empire, beginning in the 500s. The Byzantines referred to them as “Sclaveni.” The word “Slav” became a proud identification in the East, but took on the meaning of “slave” in the West with wars along the GermanicSlav border in the 800s. The Danube River 34 The Byzantine Empire, Eighth Century 35 The Byzantine Empire Converting the Slavs, 560 - ca. 1000 – Kievan Rus: In the 800s, Scandanavian raiders established a kingdom in Kiev (now in the Ukraine), ruling over a Slavic people. “Rus” became the basis for the name “Russian.” – Cyril and Methodius: In 863, Byzantine Emperor Michael III (842-867) sent two missionaries to the Slavs. They realized it would be difficult to convert a people without a written language, so they created one. They developed a Slavonic written language based on the Greek alphabet, which became known as the Cyrillic alphabet. 36 The Byzantine Empire Converting the Slavs, 560 - ca. 1000 Kievan Rus ca. mid-900s 37 The Byzantine Empire Converting the Slavs, 560 - ca. 1000 – Conversion of Russia: Christianity was brought to the Kievan Rus through a deal between Prince Vladimir of Kiev (r. 9781015) and Byzantine emperor Basil (r. 976-1025). Basil wanted to bring the eastern Slavic state under the Byzantine sphere of influence. – Princess Anna: Vladimir struck a deal: if the he could have the emperor’s sister, Anna, as a bride (despite already having several), he would convert his people to Orthodox Christianity and give military aid. Basil went forward with the deal. 38 The Byzantine Empire Converting the Slavs, 560 - ca. 1000 – Catholic Conversions among the Slavs: The popes also sent missionaries among the Slavs, and converted certain tribes— including the Poles, Bohemians (later known as Czechs), Hungarians, and Croats—to Catholic Christianity. These tribes also learned the Latin alphabet, not the Cyrillic. – “Golden Age”: By the tenth century (900s), the Byzantine Empire entered a period of prosperity and security, having absorbed the Bulgarian kingdom to the north, and extending its power from the Adriatic to Black Sea. The west remained in contact with the Byzantines, and owed them a great deal: for Justinian’s legal code, for the preservation of ancient Greek knowledge, and for being a military buffer against a great rising power in the east. 39 Islam The Arabian Peninsula In the early 600s, the Arabian peninsula was not a part of the Byzantine or Persian Empires. It had settled populations in cities, but also nomadic Bedouins, who herded goats and used camels as transportation. The Arabs were pagans, worshipping natural objects and sites. During a period of wars between Byzantium and Persia, traders rerouted their trade through the Arabian peninsula for safety’s sake, bringing the Arabs into contact with new ideas like monotheism, which they picked up from Christians and Jews. 40 Islam The Prophet – Mecca: The already wealthy city—which housed a shrine sacred to Arabs, the Ka’bah, a fallen meteorite—became even wealthier due to the increased trade caused by the Persian/Byzantine wars. – The Prophet Muhammad (570-632): An orphan who grew up in Mecca, he became a merchant who married a wealthy woman and had several children. In his fortieth year (610), he began to have visions, with the first being an angel. He was told to be the apostle to his people, and had 114 revelations over the next twenty years. – The Qur’an: Accounts of the revelations were collected after the Prophet Muhhammad’s death and recorded in scripture, which served as the basis of the book known as the Qur’an (sometimes written as “Koran” in English). 41 Islam The Religion – Relation to Judaism and Christianity: Muhammad believed the same god as the Christians and Jews had spoken to him, and that five major prophets come before him: Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. The Jews had ignored Jesus, and the Christians had added too many layers of theological complexity. – Faith: The word “Islam” means “surrender to God.” To convert, one only needs to testify: “There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his Prophet.” The most basic principles of the religion are the “Five Pillars of Islam.” – No Images of the Divine: Unlike Christian churches, no images of the divine were allowed in mosques or scriptures. Instead, Muslims use elaborate geometric patterns to decorate places of worship (the iconoclasm movement in the Byzantine Empire may have been influenced by Islam), creating some of the most beautiful non-representational art in the world. 42 Islam Lutfallah Mosque Isfahan, Iran 1600s C.E. 43 Islam The Five Pillars of Islam ① Profession of Faith: To convert to Islam, one must profess the faith and adhere to a strict monotheism. For example, the Christian Trinity (the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit) is seen as a violation of pure monotheism. ② Prayer: Muslims pray five times a day, and are called to a mosque to prat together every Friday by a human voice (not bells as with Christians or horns as with Jews). ③ Almsgiving: Muslims must give a portion of what they earn to the needy, and this donation purifies the rest that they earn. ④ Fasting: During the holy month of Ramadan, Muslims do not eat anything during the day, but feast and celebrate at night. It is time of concentrating on spiritual and family matters. ⑤ Pilgrimage: Every Muslim must make a trip to the holy city of Mecca once in his or her life. This journey is called the Haj. 44 Islam The Spread of Islam – Ignored in Mecca: Few people in Mecca paid attention when Prophet Muhammad began to tell of his visions, especially since the pagan worship of the Ka’bah brought profit to the city. – Hijra: In 622, the Prophet and a small group of his followers trekked to the small city of Medina, some 250 miles from Mecca. There they managed to convert many Bedouins, who began to focus their warfare against the unbelievers rather than on each other, unifying them into a powerful force. – Return to Mecca: The Prophet returned triumphant to Mecca and convinced the city’s leaders that his message was real. He kept the Ka’bah, convinced that the meteor was sacred to Allah (God). 45 Islam The Spread of Islam – Caliphs: The Prophet’s closest followers declared themselves caliphs, or his deputies. The first four caliphs rapidly spread Islam, conquering wide swathes of territory. Only a century after the Prophet’s death, Islam spread from Spain to India. Many non-Arabs were converted, making it necessary for them to learn Arabic. – Battle of Tours: In the summer of 732, Islamic forces crossed the Pyrenees Mountains that now border Spain and France, moving quickly into the Merovingian kingdom of the Franks. The great general Charles Martel decisively beat the Islamic forces on a field near Tours, in what is now central France, and the latter retreated across the Pyrenees. 46 The Expansion of Islam to 750 47 Islam The Spread of Islam – Reasons for Success: Despite being stopped at Tours, the overall success of the Islamic forces was remarkable. Why did they succeed? The Bedouins previously had been great warriors, but were never unified in the way that Islam united them. The warriors believed they were fighting in a war sanctioned by God, a holy war that they called jihad, and may have forced pagans to be converted or killed. – Jihad: The concept of jihad is complex because it has accrued many layers of meaning over time. Muslims identified two kinds: The “greater jihad” was the individual struggle against base desires, while the “lesser jihad” was the military struggle against infidels. The jihad against nonbelievers was a constant state of war at first, but the meaning changed over time. 48 Islam Creating an Islamic Unity: Unifying Elements Uniform Culture: Islam quickly transformed the areas it conquered, creating a uniform culture and society across vast expanses. – Language: Arabic became the language of business, government, and literature. – Prayer and Pilgrimage: These shared customs and experiences helped to create a sense of unity. – Law: Muslim law was based on the Qur’an and the Sunna, a collection of traditions based on the life of the Prophet, and led to uniform enforcement across Muslim lands. – Trade Networks: Regions ranging from India throughout the Mediterranean were connected by trade. The use of Islamic coins and even bank checks came into wide practice. 49 Islam The Gracious Life – Blending of Traditions: Muslim households blended traditions from the Bedouins and the Persians. – Women: Wealthy Persians could have an unlimited number of wives, but the Qur’an limited a man to four. Unlike in pagan Arabia, women had access to divorce and could inherit and keep property. Women were secluded from men indoors, and outdoors, continued the pagan Arab tradition of wearing heavy veils. Women also presided over the household slaves. – Daily Life: Muslims began to eat at tables rather than sit crosslegged on the floor like Bedouins. The Qur’an forbids alcohol, but some Muslims would drink wine. They also learned chess from the Persians. 50 Islam Muslims in Spain Playing Chess Figure 6.12 Photo credit: Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid 51 Islam Forces of Disunity – Shi’ite Muslims: In the mid-600s, the Prophet’s son-in-law and cousin, ’Ali, was made caliph. He believed that there should be equality between all Muslims and no special status for ethnic Arabs, who first spread Islam. He also thought the caliphs should be spiritual leaders— imams—rather than governors and tax collectors. – ’Ali’s Death: He was assassinated in 661, but followers of his idea of the caliphate persisted. Those that follow ’Ali are called Shi’ites. Husayn, one of ’Ali’s sons, was also murdered by followers of the new caliph. Shi’ites consider the caliphs after ’Ali as illegitimate, since they were not relatives of the Prophet. – Umayyad caliphate: – ’Abbasid caliphate: 52 Islam Forces of Disunity – Umayyad Caliphate: After the murder of ’Ali, the caliphate was taken over by the Umayyad family, creating a dynasty that lasted a century and based itself in Damascus. One Umayyad caliph wanted to deemphasize Mecca, so he built the Dome of the Rock mosque in Jerusalem, the place where the Prophet ascended to heaven. – ’Abbasid Caliphate: In 750, the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyad caliphate. This new caliphate wanted to make the caliph a more spiritual rather than political figure, and also moved the capital from Damascus to Baghdad, a newly built city on the Tigris River, perfectly position to benefit from the trade with the Far East. By the 900s, it was the administrative center of Islam and housed 1.5 million people. Only Constantinople rivaled it. The Umayyads contained to rule in Spain, and the Shi’ites did not recoginze the ’Abbasids either. 53 Islam, ca. 1000 54 Islam Heirs to Hellenistic Learning – Translations: By the 700s, Muslim scholars had translated scientific and philosophical works from Persians, Greek, and Syriac into Arabic. The ’Abbasids supported scientific endeavors. – Medicine: Muslim physicians were the best in the Western world, blending ancient knowledge with empirical observation. Advances included a treatment for smallpox; surgeries for cancer, vascular conditions, and cataracts of the eye. They also used a range of anesthetics. – Mathematics: Muslims brought “Arabic numerals” from India, eliminating Roman numerals and allowing more advanced mathematics. They perfected the use of decimals and fractions, and invented algebra. – Literature: The Qur’an itself, written in rhyming verse, is a vast literary achievement. The most famous work of fiction, however, was A Thousand and One Nights, which was set in the Baghdad court of an ’Abbasid caliph in 55 the late 700s.

© Copyright 2026