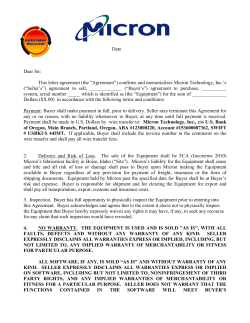

P A , E