Foreign Exchange • Purchase and sale of national currencies • Huge market in

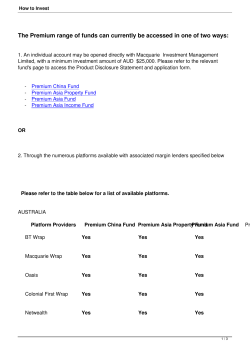

Foreign Exchange • Purchase and sale of national currencies • Huge market – $4 trillion per day (April 2007), much growth recently • Compared with US Treasury market = $300 billion • NYSE < $10 billion – Comprised of – $1.005 trillion – $2.076 trillion in derivatives, ie » $362 billion in outright forwards » $1.714 trillion in forex swaps • Concentrated in few centers and few currencies Huge growth in daily turnover Global Foreign Exchange Market Turnover (average daily turnover) Currency Turnover Most Traded Currencies Exchange Rates • Spot versus forward exchange rates • Nominal exchange rate • A forward contract refers to a transaction for delivery of foreign exchange at some specified date in the future. – Used to hedge currency risk • Forward premium Yen-dollar Spot rate Dollar Price of a Euro, Spot Forward versus futures • Forwards sold by commercial banks, otc • Futures sold in organized exchanges – Originated in 1972 in the Merc – Clearinghouse, currencies need not be delivered • Contracts settled in cash • Forward markets larger but futures markets more liquid – Options • Right to buy or sell at set price (strike price) Covered Interest Parity • Covered transactions eliminate currency risk – Let i and i* be the domestic and foreign interest rate – Let et and Ft be the spot and forward rate at t • Suppose we want to invest in foreign currency – We face currency risk when we repatriate earning – But we can hedge the risk by purchasing euros forward today at Ft – One dollar invested in euros yields euros – 3 months from now I have euros – So 3 months hence I have dollars Covered Interest Parity • Arbitrage requires that – Which is called CIPC • This implies • or Ft et i i * et 1 i * – If not equal there are arbitrage profits to be made – Thus, a positive interest differential implies a forward premium – Interest must compensate for capital loss Covered Interest Arbitrage Interest Parity Line 0.04 D A Ft et et 0 C B -0.04 -0.04 0 i i* 1 i * 0.04 Adding Transactions Costs 0.04 D P A L PU Ft et et 0 C B -0.04 -0.04 0 i i* 1 i * 0.04 Don’t Try This CIPC • Take logs of both sides of CIPC – or, for small i • Most studies show that CIPC holds – Notice that there is no currency risk – Forward price signals markets expectation Riskless Arbitrage: Covered Interest Parity • Arbitrage profit? – Considers the German deutschmark (GER) relative to the British pound (UK), 1970-1994. – Determine whether foreign exchange traders could earn a profit through establishing forward and spot contracts – The profit from this type of arrangement is: Covered Interest Parity Uncovered Interest Parity • Suppose we do not hedge our investment • Again we invest one dollar – Let be the expected future spot rate – In 3 months we earn – Arbitrage requires – UIPC, thus CIPC and UIPC compared • The two conditions differ only in one term – versus – CIPC involves no currency risk – UIPC bears currency risk • Holds only if agents are risk neutral • Risk averse agents may require a risk premium – Notice that if then UIPC holds • This would be cool => markets reveal expectations – We can test for this Efficient Markets • Example of Efficient Markets Hypothesis – Investors use available information efficiently – Does not mean they are ex post correct, only that prices reflect all available current information in an efficient manner • Unbiased errors • If I am efficient my error pattern looks like that of Tiger Woods – Of course, the variance of my pattern is greater, but we are both on target on average Market Efficiency Testing for UIPC • We have data on F but not on • Rational expectations implies that forecast errors are unbiased – Then should be an unbiased predictor of et 1 • That is, guesses are on average correct • UIPC implies that eˆt 1 Ft – Thus, if REH and UIPC holds, then Ft should be an unbiased predictor of et 1 • => market is efficient!!! – What does unbiased mean? • If I have a lot of observations, then the average value of Ft should differ from et+1 only by a random error – Hiawatha’s Last Arrow Euro Six Months Forward Testing UIPC • So if I estimate et 1 Ft X t t – where X t is any variable you can think of, and t is a random error • I should find • That is, all the information valuable for predicting et 1 is incorporated in the market price, Ft Testing UIPC • Typically one actually regresses changes, so • With null hypotheses – Notice this is a joint test • REH and UIPC • So rejection could mean either – Expectations are not rational – UIPC does not hold (perhaps agents are not risk neutral) • Visual inspection does not vindicate UIPC Empirical Test of UIPC Yen Spot and Forward Actual change in spot rate and forward discount Tests of UICP • Most tests find forward premium puzzle – Not only is 1 in the data, it is often negative • If UIPC held, the pound should, on average, appreciate when it is at a forward premium, i.e., f > 0 • The negative point estimates of β imply that the pound actually tends to depreciate when it is at a forward premium. • UK interest rates exceed US by 2.41% on average, but sterling appreciates by 22.25% Forward Premium Puzzle • If UICP fails there are two possibilities – Markets are not efficient – risk premium is missing • We are testing a joint hypothesis • If marginal agents are risk averse ignoring this could explain the forward puzzle • If income is volatile perhaps risk premium varies • Or it could be Central Bank Behavior Central Banks • Central Banks move exchange rates in short run – They could set policy based on observations of F • E.g., intervene when risk premium rises • Seems that when CB’s intervene heavily the forward discount increases – Forward discount is larger in floating rate regimes – Forward discount larger at shorter horizons • Interesting because CB’s can only move e over short periods • Less risk at longer horizons Estimated Beta at different horizons Short Horizon Tests Longer Horizons Risk Premium • But time varying risk premia hard to observe – To explain 12 risk premium must be more volatile than • Why would this be the case (assertion, see notes for explanation)? – We don’t seem to be able to find such a risk premium • Why is forward discount larger for industrialized economies? – Unlike major currencies, which generally show a coefficient significantly less than zero, suggesting that the forward rate actually points in the wrong direction, the coefficient for emerging market currencies is on average slightly above zero, and even when negative is rarely significantly less than zero. – Hard to reconcile with risk premium explanation • Emerging markets appear riskier but have a smaller risk premium???? DXY Index Can we make money? • If UIPC fails, can we make money? – One can pursue carry trade: borrow low invest high – Let y be the amount of money borrowed, then – With payoff – So if my profit would be Carry Trade • Suppose we did this via dollar-yen – September 1993 till August 2003 • • • • Bet once a month for ten years, we have 120 observations We would earn money, average profits positive = .0041 Profits are volatile Sharpe ratio = 0.12 < than for S&P 500 .6 to 1.1 – Carry trade is a bet against arbitrage, on lower volatility • Sometimes carry trade leads to big losses, unexpected currency movements – Like selling puts out of the money • Why don’t investors arbitragers bet against it? – Incentive problem for fund managers – Rational inattention Example Example – Example: Japanese yen and Australian dollar • 2001: steady increase in profits from carry trades. • Despite several months of positive carry profits, the yen did not sufficiently appreciate against the Australian dollar to offset these profits. – Leverage and margin • Example: You have $2,000 and borrow an additional $48,000 in yen from a bank in Japan. – You have borrowed 25 times your own $2,000 capital, a leverage ratio of 25. You conduct carry trade, investing $50,000 in the Australian dollar. – If you lose 4% on the trade, you’ve lost your initial capital investment. This initial capital put up by the investor of 4% of the total investment is known as a margin. Summary • Obviously if large institutions do this losses could be huge. Duh! – Even if expected returns from arbitrage are equal to zero, actual profits are often not equal to zero. – Returns (profits/losses) are persistent. – Returns are volatile/risky. US Dollar/Yen Exchange Rate Price Pressure • Bid-ask spreads reduce size of profits • Large amounts of speculation needed to earn money – Speculator who be one pound on an equally-weighted portfolio of carrytrade strategies (across the USA, Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Switzerland and the euro) from 1976 to 2005 would earn an monthly payoff of 0.0025 pounds. – To earn an average annual payoff of 1 million pounds would require a bet of 33.33 million pounds per month. • Is there an effect of such large trades? – Would they survive such speculation? – Prices rise with order flow • Could eat profits – You could break up trades, but this chews up profits as well – The marginal expected payoff can be zero, even when the average payoff is positive • Speculators make profits but no money is left on the table Risk versus Reward • Idea: Examine traders’ strategies and other finance theories to study tradeoff between risk and return. – Data: Positive 1% interest differential is associated with only a 0.23% appreciation in the currency, implying a 0.77% profit. – Problem: despite the existence of profits: • Profits do not rise/fall linearly, line is a poor fit for the data. At higher differentials, variance in return higher. • Variance around the line is high in general, creating uncertainty for investors. Test of Efficient Markets • Not the high variance of observations around the line of best fit • Observations do not cluster around the line of best fit – For the same interest differential there are vastly different actual rates of depreciation observed Limits of Arbitrage • Returns positive for currencies • Very high volatility of returns • Sharpe ratios < 1 – Equal to 0.5 – 0.6 for market portfolio of currencies – Differs little from stock market • Puzzle like the equity premium puzzle Predictability and Nonlinearity • Linear model may be the problem • Nonlinear models reveal that low interest differentials are associated with very low profits. – At high differentials, investors engage in carry trades, bidding up the currency, sometimes causing reversals (and losses). – At the extreme ends, arbitrage appears to work, so what is happening for moderate interest differentials? • Investors are willing to take on some risk, if the return is large enough. Peso Problems • Could be due to peso problem – Samples used in tests are not long enough to have big losses • Suppose you studied the dollar-baht rate for UIPC, 1990-1997 • You miss a big depreciation in July 1997 but investors may have considered it a possibility – Suppose e = 20c, and investors are 95% sure it will stay – With prob = .05 they believe it will fall to 10c. Then, • So each period for which there is no change the forecast error is positive: • Casual observer might assume irrationality Example • Suppose peso is pegged to dollar – Let iUS .05 – Then UIPC implies – Market predicts depreciation; each period the peg holds UIPC is violated • • • • But does not mean market is inefficient Agents are calculating the small risk of a big depreciation When the market corrects, losses are large Argentina, Hong Kong Hong Kong Peso Problem Argentina Peso Problem Thailand / U.S. Foreign Exchange Rate Realized Profits on Yen Carry Trade Realized Profits on Yen Carry Trade Yen Positions of non-commercial traders at the Merc UIPC Regressions, in Sterling Volatility Puzzle Implied Yen Volatility (3 month) Implied Yen Volatility (3 mo) New Zealand 3 month T Bill 9 100 8 90 7 80 6 70 5 60 4 50 3 40 2 30 1 20 int diff yen per NZD Yen per NZD NZD Yen Interest differential Yen/NZD Spot Rate and the Interest Differential Real Interest Parity • We have been looking at nominal returns, what about real returns? – Fisher effect tells us that – So – If PPP holds, then so – But PPP is too restrictive an assumption • What happens in general? Real Interest Parity • We need to consider expected changes in Q – So, – If inflation and exchange rates change at the same rate there is no change in Q – UICP implies – so RIPC • So, using the Fisher equation we obtain: – This implies that real interest differentials are equal to expected changes in Q – Suppose people expect Q e 0 – Implies real value of the dollar will decline • Investors will demand a premium to hold US assets • Does this mean there are profits that are not arbitraged? – No • Differences in real returns are not on the same asset • They are returns on different bundles of goods RIPC Interpreted • Real interest differentials reflect nominal rates deflated by ' s over different consumption baskets – If agents were identical => PPP, so differences equalized – Because people in different countries consume different baskets of goods, there is no way for them to arbitrage away any difference. • Implies that we cannot look at real interest differentials to study whether capital markets are integrated – Capital markets can be perfect, but if large US CA deficits lead to expectations of Qe 0 then real returns on US assets would have to exceed those in the rest of the world Exchange Rate Regimes • Two polar cases and many in the middle – Fixed exchange rates • CB buys or sells reserves to maintain a set price of foreign exchange – Flexible exchange rates • CB does not intervene in market for foreign exchange • To understand, suppose demand and supply of foreign exchange given by Historical View on Exchange Rate Regimes Fixed versus Flexible • Shouldn’t e be determined by market forces? – Mundell versus Friedman – Foreign exchange is not like a normal market • Exchange rate is like a dictionary – Exchange of national currencies, fiat monies • A high price of foreign exchange does not lead to more supply • No fundamentals driving the market • Government policy must control supply of money – Then why should they be flexible? Friedman on Flexible Rates • If internal prices were as flexible as exchange rates, it would make little economic difference whether adjustments were brought about by changes in exchange rates or by equivalent changes in internal prices. • The argument for flexible exchange rates is, strange to say, very nearly identical with the argument for daylight savings time. Isn’t it absurd to change the clock in summer when exactly the same result could be achieved by having each individual change his habits? All that is required is that everyone decide to come to his office an hour earlier, have lunch an hour earlier, etc. But obviously it is much simpler to change the clock that guides all than to have each individual separately change his pattern of reaction to the clock, even though all want to do so. The situation is exactly the same in the exchange market. It is far simpler to allow one price to change, namely, the price of foreign exchange, than to rely upon changes in the multitude of prices that together constitute the internal price structure. Foreign Exchange • If CB does not intervene, then market price of foreign exchange is • Suppose demand for foreign exchange increases – Then if CB does nothing, e must rise – To keep e fixed CB must sell foreign exchange • So international reserves fall – Thus, • where is the fixed exchange rate • Notice that exchange rate can also be affected by policy – By affecting demand or supply Fixed Rates and Reserve Accumulation • If the exchange rate is fixed, then reserves adjust as demand and supply shifts – The peg is sustainable if these shocks offset – Peg is unsustainable if shocks are biased – But there is asymmetry • Easier to accumulate foreign exchange • You cannot print it if you are running out! – When does a fixed rate collapse? • When reserves run out? No. Time to Collapse • Suppose that the peg is unsustainable – When reserves run out the rate must collapse to e • Implies that e will jump at that date, t • Implies capital gain at date t – 1 • So people will sell at t -1, implies capital gain, so e collapses at t – 1 • Implies e collapses at t – 2, … • So e must collapse at earliest date at which there is no capital gain – So e collapses before all reserves are depleted • Why not sell before tc ? • Because then they incur capital loss Collapse • Exchange rate collapses before reserves run out – Nobody wants to be the last person to exit – If agents are forward looking they anticipate capital losses • So currency cannot collapse and then jump to shadow rate – In practice we see that currency collapses before reserves run out – Key is when CB is no longer willing to pay the cost of maintaining the exchange rate • CB could always repurchase the MB – Problem is the cost of doing so » No longer lender of last resort, interest rates may skyrocket – External versus internal balance Foreign Exchange Reserves and MB, Sept 1994 (pct of GDP) Fixing the Exchange Rate • Under fixed rates IR is changing to offset any excess demand for foreign exchange – When there is ED > 0 the CB sells reserves, so – If ED < 0, the opposite takes place • What is the effect of this operation? – Suppose no sterilization • That is no attempt to offset the operation of pegging the exchange rate on the domestic money supply No Sterilization • Start with the CB’s balance sheet • The assets of the CB, IR + DS = MB • The money supply just depends on the MB, so – Thus when reserves fall the money supply contracts, and vice versa – Fixing the exchange rate means giving up control over the supply of money Example • Central bank balance sheet condition: – Example: • Suppose the government purchases 500 million in domestic bonds and 500 million in foreign assets (reserves). • Money supply is therefore equal to 1000 million pesos. Central Bank Actions • Suppose the Fed purchases foreign exchange – 4 cases 1. purchase from home-country banks: • 2. purchase from home-country non-bank residents: • 3. in this case, residents would receive payment in the form of currency in circulation. purchase from foreign banks or central banks via changes in the foreign bank’s deposit at the Fed. • • in this case, residents would receive payment in the form of currency in circulation. purchase from home-country non-bank residents: • 4. in this case alongside the increase in IR is an increase in bank reserves. In this case, once the bank uses this deposit to purchase some interestbearing security from a domestic bank, bank reserves will rise. In all cases, the reserve transaction results in a simultaneous change in MB Sterilization • Sterilization occurs when the CB moves to insulate the domestic economy from foreign reserve transactions – Typically an open market operation: if inflows of foreign exchange are swelling the money supply then the CB sells bonds to soak it up, e.g., – Notice that to persist in sterilization requires large stocks of both foreign reserves and domestic securities. – obviously difficult for debtor, what about for surplus case? – Need to keep selling DS, but how much will the public buy? • Depends on how financially developed the economy • Interest cost of sterilization can be large Effect on Monetary Policy i M P 0 M P1 IR P i0 i1 L(Y, i) M/P Impossible Trinity • We see that a country cannot simultaneously have: – Independent monetary policy – Fixed exchange rate – Capital mobility • With fixed e you interest rates cannot diverge from i* • Conflict between internal and external balance – China’s “advantage” • China does not have open capital account – So it can sterilize current account surpluses – Lack of capital mobility depresses local interest rates, reduces costs of sterilization – Effect of large sterilization in some countries could be future inflation Carrying Costs (pct of GDP) Foreign Reserves net of currency Valuation Changes on Foreign Reserves China Balance of Payments Transactions Capital Account Components Annual Changes in NFA, NDA, and Reserves Time of Collapse Reserve Flow Sustainable exchange rate Unsustainable Exchange Rate Mexico’s External Balances Ruble Exchange Rate Monetary Base and Gross Reserves Russian Foreign Exchange Reserves (billions of $) MB = $6.7 billion in Sept 1998 Market for Foreign Exchange Varieties of Exchange Rate Regimes

© Copyright 2026